Dorion Sagan on Carl Sagan, Lynn Margulis, and his new book, Cracking the Aging Code

In this interview I talk with Dorion Sagan about whether his father Carl Sagan used LSD, his mother Lynn Margulis’s paradigm-changing theory of symbiogenesis, her thoughts on psychedelics, and his new book Cracking the Aging Code: The New Science of Growing Old-And What It Means for Staying Young, which he co-authored with Josh Mitteldorf.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Dorion Sagan is an award-winning science writer, and has co-authored, contributed to, and edited over thirty books including: What is Life?, Death & Sex, Microcosmos: Four Billion Years of Microbial Evolution, Into the Cool: Energy Flow Thermodynamics and Life, Dazzle Gradually: Reflections on the Nature of Nature, and Cosmic Apprentice. He’s also written for Wired, Whole Earth Review, The New York Times, and Psymposia.

I met Dorion in 2014 after the first Psymposia event at UMass Amherst where I was completing my BS in Plant, Soil, and Insect Science. We first met at a bar during the after-party where he was enjoying the inebriating effects of his favorite drink, Kentucky bourbon and soda. We kept running into one another at the local café, and over the next year we rolled many cigarettes and had many conversations and bullshittings about life, science, deep time, plants, drugs, philosophy, symbiosis, and evolution. He was a big inspiration for Psymposia early on.

Thanks Dorion for talking with me. What are your favorite psychoactives?

I’m drinking coffee and Belgian hot chocolate as I read this in Providence. These are Lovecraft and Poe’s old haunts. So, on the principle that actions speak louder than words, I could say for the moment that cacao and coffee – keeping me warm and helping me write—are among my favorite psychoactive plants.

Nietzsche, William James, or Whitehead?

Yes

Ok enough fooling around. Carl Sagan and Lynn Margulis were your parents, and two of the most significant scientists of the 20th century. Everyone knows about Carl Sagan and the Cosmos but less about Lynn Margulis and the Microcosmos, even though her work is arguably more paradigm shifting to evolutionary science. What can you tell me about that?

Well, my dad died in 1996 and his posthumous influence, for example on the Internet and on the new Cosmos show with Neil deGrasse Tyson, lingers on. My father presented the science of the enlightenment and renaissance, starting with the basic ideas that the sun is just a star, and the Earth is not central, and the universe is vast and may contain other life forms, to a mass television audience. That was a big deal, as was his attempt to moderate religious thinking in a culture ready to have more sophisticated ideas.

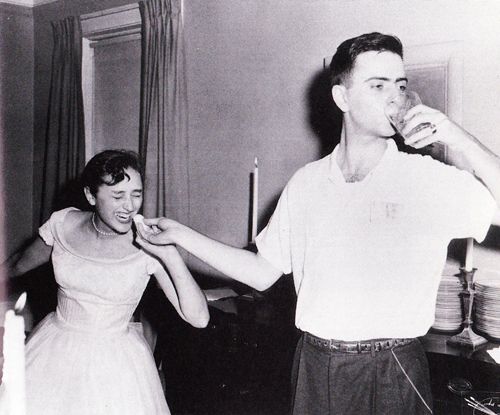

As you suggest, far more people are aware of the personality and contributions of my father—he was, for example, supposedly responsible for orchestrating Voyager spacecraft to turn around on Valentines Day and shoot the image of Earth from outside the solar system—the image of our world taking up a fraction of a pixel in the digital photograph from that distance. He was a great educator, and infected many people with a love for science, including my mother, who was a teenager at the University of Chicago when they first started dating in 1953.

Still, in terms of pure science, hers was the bigger contribution. She showed that the cells of our bodies—and those of all plants, animals, and fungi—came from mergers of bacteria. The oxygen-using parts of your cells are mitochondria, and they have their own DNA. She used multiple sciences, from paleobiology and geochemistry to microbial ecology, as well as surveying the international literature, to build her case. It is now considered proven—and taught in textbooks—by genetic sequencing data. The mainstream evolutionary biologists, the neo-Darwinists, who fought tooth and nail against the notion that organisms can evolve suddenly, “a genome at a swallow” as she said, are now busy trying to appropriate my mother’s (and others’) once extremely heterodox and unacceptable ideas as if they knew them all along.

My father, whose program Cosmos was in its the time the most seen television show in the world, was undoubtedly a great and charismatic scientific educator. But he essentially made cool and sexy ideas developed in the Renaissance. In terms of original science, it’s clear that my mother’s contributions were greater. She was elected to the National Academy of Sciences although he never was. She advocated [to the members] that he be accepted, and [remarked] that it was jealousy that kept him out; she was willing to tell him the individuals who had argued against his inclusion but he apparently said he didn’t want to know who they were, as it might prejudice him against them.

It is important to choose your parents well and in this particular area, at least, I think I am to be highly commended. I sometimes think of Carl Sagan as my Sky Father, and Lynn Margulis as my Earth Mother.

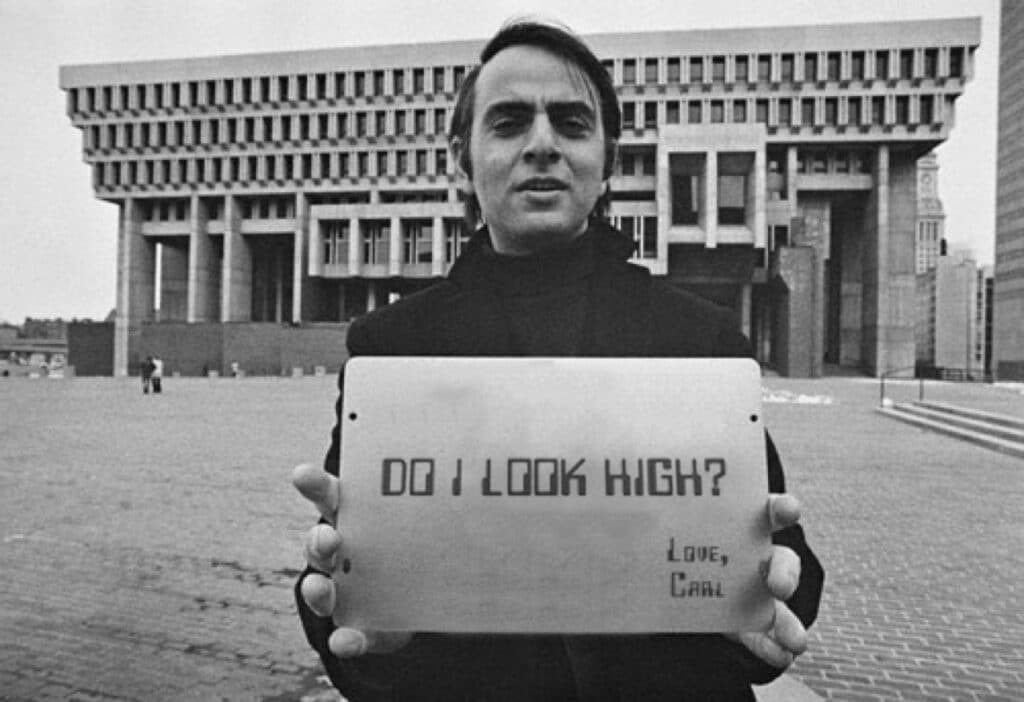

Carl enjoyed marijuana. Do you know if he ever used LSD?

I’m sure my father smoked pot, as I smoked with him a number of times, and sometimes we’d have interesting discussions, for example, when I spoke with him about Otto Ranke’s Birth Trauma and he brought up cosmological speculations about infinite cycles of contracting and expanding universes, a discussion which informed his essay, “The Amniotic Universe,” in Broca’s Brain. When I was 20 or so we talked about LSD and he said he’d never taken it but was interested.

I offered to take it with him, and suggested that the nearby greenery and scenery—gorges and trees and fresh water and blue skies—would be a good place to trip. For better or worse, he never took me up on this suggestion and I have no evidence that he ever did psychedelics. My mother suggested it might be too jarring for his ego, as psychedelics are known to hand people their ego and can be difficult for everybody, especially those with a desire to maintain their mastery, authority, or intellectual control.

That doesn’t mean that he never did them afterwards. He did meet with Terence McKenna, visiting his greenhouse full of psychoactive plants, and with Timothy Leary, who in jail made claims about aliens [contacting him]. It is possible that he did try psychedelics but kept quiet about it—he was clearly concerned not to let the weed cat out of the bag, which is why he published his positive experiences only anonymously as Dr. X in Lester Grinspoon’s Marihuana Reconsidered. (I was only twelve when I read it in 1971 but figured out it was him.) In the end he was hardly a druggie. He drank a sip or two of wine, never to get drunk and only on social occasions. When I was a college student he told me he worried about mixing alcohol and cannabis. He didn’t even drink coffee, preferring tea. He was a chocoholic.

What is symbiogenesis?

The essence of Lynn’s ideas are couched in the terms endosymbiosis and symbiogenesis. Symbiosis is when two organisms of different species live together for most of their life cycles in intimate contact. Endosymbiosis refers to organisms living their lives within one another—it is like sex, but permanent. Well, it turns out that such matings, though between beings from different species, can have fertile offspring.

The offspring, however, are not a recombined organism so much as a merged one. The evolution of a new species from two species coming together like this is called “symbiogenesis,” [and the science which studies such mergers may be called symbiogenetics]. Hollywood thinks it’s on the cutting edge when it mentions “cross-species genetics” in a comic book superhero adaptation.

The truth is we are all multiple monsters that combine many species. The animal cell itself is a symbiotic merger between archaea and bacteria. Plant cells have a third bacterium with its own DNA joining the permanent, productive, ecological party—the green parts of the plant cells, the plastids or chloroplasts, come from cyanobacteria.

Truth is stranger than fiction and Lovecraft and Poe teaming up would be hard put to outdo the image of crowded life evolving more complex cells from wild permanent mergers of symbiotic bacteria. Cells which then, in cloned, sexually reproducing forms, evolved into land-based plants and animals like us—each of us a vast society deluded into thinking we are “individuals.

Lynn’s contributions to our understanding of life on Earth, especially the eighty percent of life’s history before plants or animals evolved offers a very rich legacy to our changing understanding of who we are—think of the growing talk of the microbiome—the role of microbes in our gut to our health and mood.

She often debated with Richard Dawkins. He’s been making videos about the hate mail he receives. Is he still being selfish with his genes?

Lynn had a famous debate with Richard Dawkins in Oxford in 2009, sometimes called “The Battle of Balliol.” The debate was moderated by Denis Noble, one of Dawkins’ professors and on his thesis committee. Dawkins and the neo-Darwinists with their Selfish Gene Theory made important contributions but prematurely mathematized the science, giving what British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead called “misplaced concreteness.” Although they now accept that we and all life forms are “symbiotic monsters”—vast collections of cells many of which themselves have multispecies bacterial symbiotic ancestry—they still cling to the notion that symbiosis is rare in evolution. This is hardly true, although the origin of eukaryotic cells (ameba-like cells of the type we and all plants, fungi, and animal tissues are made) is notable for marking a radical upgrade in surface life’s basic module of organization.

For example, it is now known that new species of insects evolve depending on their associations withWolbachia bacteria. This may be why there are so many beetles. When we consider that animals as different as termites and cows can only digest their food (wood and grass, respectively) because of the microbes they contain, it should not surprise us so much.

The most immediate and important influence for Dawkin’s Selfish Gene theory was William D. Hamilton. Dawkins called Hamilton, “my intellectual hero,” and the “nearest equivalent we have to Darwin in the 20th century.” At a meeting on the evolution of sex Lynn Margulis referred (fearlessly, as usual) to neo-Darwinists as “puerile numerologists.” In the strange math of merging symbiotic bacteria, or a sperm and egg cell for that matter, 1 + 1 does not = 2. No, 1 + 1 = 1 : one organism is the result of the merger, in which the new organism acquires the genes of both “parents.” This is lateral genetic transmission and huge in evolutionary theory – so huge that it is really incorrect to think of life on Earth as a “tree” – the “roots” are too entangled, and they continue to grow into one another on a crowded planet.

The language of life is chemistry, not mathematics, Lynn emphasized. Genes cannot be selfish (I once said, and she repeated the comment), because genes are not selves. The earliest detectible self is the cell, or the organism made of cells. Nascent selves are represented at a more nebulous, but still very real level by termite mounds, bee hives, and technoscientific humans organized into warring nation states.

In The Narrow Roads of Gene Land, Volume 2, William D. Hamilton calls Margulis “a high priestess” (perhaps getting her back for her numerology comment). But tellingly, late in his life he collaborated on scientific articles on the Gaia hypothesis, which studies Earth’s geochemistry, its own nascent physiology, which shows aspects of active stability – for example, regulation of atmospheric chemical composition and planetary temperature regulation over time spans of hundreds of millions of years – reminiscent of the physiology of an animal.

Hamilton imagined clouds as ways for microbes to spread themselves, and he wanted his own body to be returned to the Amazon rainforest. A true naturalist, he spent many hours in the wilderness with organisms; and his contraction of the protists (ameba-like cells) Giardia and the protist Plasmodium (which spreads via mosquito-born malaria) were with him for his entire life; I would argue that alone shows the folly of thinking of organisms too exclusively as mathematizable “individuals.”

Lynn experimented with LSD when she was younger. In “An Open Letter to Mr. Joe K. Adams” published by thePsychedelic Review in 1964 she’s said:

“I really do agree with your contention that the drug (LSD) attacks defense mechanisms built up carefully to conceal the truth of our direct sensory perceptions. One would a priori imagine, however, that a drug which forced us to see the world as it is would be welcomed. Why, then, is the entire ‘consciousness expanding’ drug movement confronted with enormous hostility?” She clearly got the message, but did she hang up the phone?…

My mom told me that she took LSD in a medical setting under direction of my father’s cousin, Eugene Sagan, when it was legal. From her account of it to me, she in no way freaked out but, rather, found it mildly amusing: the men in lab coats who administered it to her looked like “big babies” she said; and she found that she could adjust the sound and treble of the music they were playing by adjusting her ears. I don’t think she ever got high on weed, although she did show off once by smoking it with her Columbian friend in front of me and my brother one time—she didn’t like what it did to people (made them less productive, in her view), and I doubt she tried it enough times to get high. I do think she had a natural nature mysticism, and there are passages in her letters that seem to refer to a profound experience in nature as a young woman in the midwest.

As far as “once you get the message, hang up the phone”–Alan Watts’ advice on taking psychedelics—I think she already had the message irrespective of psychedelics. Her CV does mention going to Mexico to study indigenous and traditional medicine in her mid-teens; when one looks at “shamanic” paintings such as those of Pablo Amaringo, the interpenetration of biomorphic forms seems almost a visualization of symbiosis theory and bioenergetics, so there was definitely a cultural, if not a psychedelic influence there.

In the same letter she says,

“The excitement here arises from our present position: we are probably on the threshold of a physical basis of consciousness. Perhaps our times are analogous to those at the beginning of the century, which culminated in today’s clear concept of the physical basis of heredity.”

This is somewhat anathema in psychedelic circles…

Sure, it sounds naive to me too, but remember this was in the 1960s when huge money was coming into the government to compete in general and space science with the Soviets, who with Sputnik had launched the first satellite. It was the start of Big Science. The discovery of the chemical structure of DNA and its role in the biochemistry of reproduction was epic. At the same time my mom was naively hoping to maybe use psychedelics as an “intellectuoscope” into the true workings of the brain, my father was writing letters comparing the voyage of ships to other planets to the European Age of Discovery, ships setting off to discover “new worlds” in the 15th century and so on.

So there was great general excitement. On the other hand, she still has a point, in that studying brain chemistry via psychedelics and other substances may still yield many discoveries unavailable to less experimental frames of inquiry like philosophy and behavioral psychology. I think her initial excitement for psychedelics as a chemical key to unlocking consciousness waned.

She visited Timothy Leary in Millbrook, NY and was disenchanted with the half-naked women and guru act of the former clean-cut Harvard psychologist, who now had his young daughter in a box recording her emotions while on LSD. However, I think my mother never lost her faith in the scientific power of chemistry—including biochemistry, and geochemistry—to reveal life’s truths. Remember the role of DNA in life is only one of many discoveries in the understanding of how energized chemicals interact to produce living systems; increasing our understanding of the brain and the chemicals that affect it may still may be among the best ways, or the best way, to illuminate the mysteries of consciousness.

So, what is life?

“Life is what happens when you’re making other plans,” to quote John Lennon.

Ok, let’s talk about your new book. It’s 2016 and we really don’t know why we age. Cracking the Aging Code,which you co-authored with Josh Mitteldorf, argues that aging, actually evolved. Tell me more.

Aging has long been the province of shamsters, telling people what they want to hear. Religion, in so far as it promises surcease from death, can be considered an anti-aging scam. Today, in the US alone, a billion dollars a year are sold in antioxidants, touted to quench free radicals, the cause of aging. But this model of aging imagines us as a kind of machine inevitably succumbing to the biological equivalent of rust. In fact, life has mustered its resources to counter free radical damage ever since the Earth’s atmosphere was oxidized starting some two billion years ago.

The atmospheres of Mars and Venus are over 90% carbon dioxide but we have 20% oxygen in ours (and only a trace of CO2). The cyanobacteria, mutating in photosynthesis to use water as an electron donor, began releasing reactive oxygen into the atmosphere in massive amounts. Predecessor photosynthetic bacteria, the purple sulfur bacteria, got their hydrogen from hydrogen sulfide and excreted balls of sulfur. But the fabulous spread of green bacteria, later symbiotic as the green parts of plants, taught life to deal with oxidation and free radicals. In fact, we use free radicals in our immune system, to destroy invaders and to shape ourselves in utero for example by destroying the webbing between our fingers and toes. Indeed, surface life in general found ways to detoxify reactive oxygen and then use it as an energy source.

All plants and animals alive ably use oxygen in combination with food or carbon in carbon dioxide to grow their complex tissues. The biggest anti-oxidant study, on male smokers in Finland, was discontinued when the subjects given antioxidants (vitamin E in this study) began dying statistically more often. There is more but the bottom line is the most accepted “scientific” study, that free radicals make organisms wear out over time, doesn’t hold up. As you know life can repair itself: it can heal, it can grow and grow stronger (up to the time of adolescence), blood clots, the immune system destroys nascent cancers by apoptosis—programmed cell death deploying free radicals and so forth.

The free radical theory of aging was put forth by an industrial chemist and it doesn’t stack up against the evidence. Evolutionists realized that the body has self-healing properties and that life as a whole has survived for billions of years, and many microbes can divide indefinitely without anything resembling aging unto death. But death, and the aging that leads there is commonplace in many animals.

Using a version of selfish-gene theory modern evolutionists proposed that genes that help one reproduce early in life may turn against the body later in life. This is called antagonistic pleiotropy. The most accepted evolutionary aging theory suggests that not genes but energy limitations cause aging. It is theorized, in the disposable soma theory, that the energy used to reproduce robs the body of the resources necessary to continue repairing itself, and that aging, and then death, is the inevitable result.

However aging as an increased chance in dying is not observable in all animal lineages. Turtles and sharks have no increased chance of dying year over year. Moreover, fruit flies have been selected for longevity until they live eight times as long, with no decrease in fertility. Therefore these evolutionary theories share with the free radical theory the virtue of putting forth a reasonable explanation but also the vice of not matching with the evidence.

Salmon are flooded by hormones after reproduction and die immediately. Whales (like the bowhead whale) live hundreds of years and clams, judged from their growth rings, can live several hundred years. Aging is plastic, not inevitable.

The thesis of Cracking the Aging Code is that in lineages where there is a tendency to reproduce too fast, aging has evolved because it helps the population not die out from running out of resources, particularly food. This matches with the data that caloric restriction make multiple species live longer. A species which destroys its food source, or pollutes itself to death, or is laid to waste by an epidemic leaves no offspring.

The aging theory in the book suggests that aging has evolved to protect populations, which cannot survive if they overgrow their ecosystems. This contradicts selfish gene theory which imagines that whoever spreads the most genes is an evolutionary winner. The math here makes evolution seem more scientific but in fact populations that destroy their resource base disappear forever, and this important phenomenon has not been introduced into evolutionary models in a credible way until recently.

A species like the Rocky Mountain Locust may have depleted its food supply immediately prior to extinction. There may be huge evolutionary advantages to organisms that evolve means of controlling their population growth. Aging unto death should probably be seen in this context, as a possible adaptation. If this is true not only do we have to revamp biology to include the advantages to groups of individual deaths by aging, but also question the assumption that whatever is natural is good for us as individuals.

The variety of aging schedules in species, including beings such as carrion beetles and hydrozoans that if stressed can age backwards, returning to earlier phases in their normal development, suggest beyond a doubt that aging is built-in, genetic, in those species which exhibit it. In the book we suggest that human aging occurs via shrinking of the thymus gland, through rationing of the enzyme telomerase, through apoptosis, insulin-related mechanisms, and also inflammation. The idea is that aging has been so beneficial to our ancestors that dying is kept on a genetic leash through aging.

The good news is that this means that we can add years to our life—for example by taking low-dose aspirin and ibuprofen, mediating aging, and by something as simple as eating less—because these things interrupt the aging pathways in their evolved logic to control overpopulation. Eating less would act as a physiological signal that the population is no longer in danger of overpopulation and consuming its food supply.

Life, the planetary phenomenon that produced human intelligence, is not a machine but a sensitive, if mostly unconscious intelligence that can respond to ecological signals to perpetuate its kind. We argue that survival is not only an individual, but a group phenomenon. And this analysis merges with my mother’s vindicated analysis on the importance of symbiosis—groups of a different sort—in evolution. No man is an island, and no organism is a true loner. There is power in numbers and social beings, especially if they have a tendency to grow too fast, and may have long been selected for their ability to remain ecologically stable. This is the basic idea of the book, and it has major implications for health and longevity, as well as for mainstream evolutionary theory.

Any advice for young people who are fighting to end the war on drugs?

A word of advice—don’t give it. The war on drugs, what is it? It seems to me an incoherent motley of legalisms. There is no escape from drugs in life because we are made of, grown from chemically active natural substances. The Greek word for drug, pharmakon, means both cure and poison. The botanist Paracelsus, who founded toxicology, said the “poison is the dose.” I think the war on drugs is incoherent philosophically. Life is a cosmic biochemical phenomenon, expanding into its environment. Whatever the hypocritical legalisms, life will continue to experiment, for better and worse, with the sort of substances of which it itself consists.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.