This is part two of a six part series on the intersection of psychedelics and capitalism, and the early investors making it happen.

It feels a little surreal to be sitting in a Manhattan WeWork ballroom with a group of medical researchers, venture capitalists, and pharmaceutical executives who are licking their chops in anticipation of what some are calling the next “short-term bubble” for investors. This is where the 2020 Green Market Summit on the Economics of Psychedelic Investing is unironically taking place. Everything is trimmed in gold, the curtains drape 20-feet from floor to ceiling, and the room is abuzz with excitement between panels that include: “Intro to Psychedelic Markets;” “The Market for Microdosing;” “Business Strategies for Psychedelic Companies;” and “Parallels Between Cannabis and Psychedelic Companies.” It’s like no one in the location planning stages had read any of the dozens of articles titled some variation of “The Epic Rise and Fall of WeWork.”

Founded in 2010, WeWork was on track to become the biggest lessee of new spaces in America, renting millennials’ dream coworking spaces to a generation of gig economy workers, freelancers, and entrepreneurs. Workspaces included lofts of claim-your-own desk space, booths with projector screens, couches, alcohol and coffee on tap, a “no meat” policy, and on-site meditation and yoga classes.

WeWork’s visionary and founder, Adam Neumann—whose first two business ventures included a brand of high heels with collapsible heels and baby pants with knee pads—told the New York Daily News that “during the economic crises, there were these empty buildings and these people freelancing or starting companies. I knew there was a way to match the two.” So, he bought up property, started a coworking space called GreenDesk, sold it, then started WeWork. And, for a while, people were excited about the business, which achieved “unicorn” status in the investor world and a $10B valuation by 2016.

In 2017, WeWork gained another $10B in valuation after receiving huge investments from the venture capital platform SoftBank, and began a heavy expansion into China. And, by 2019 WeWork was valued at $47B, even though, as The Guardian points out, they really had no evidence that they could produce profits. The Guardian also notes several other factors which indicated WeWork had started spiraling downward, including Neumann’s “weird” behavior—such as allegedly smoking weed on his private jet rides, and flying all of his employees to mandatory workforce summits called “Summer Camp” that cost the company at least $2,500 a head—and allegedly self-dealing and self-enriching himself by frequently selling off stock and leasing buildings to WeWork that he, personally, had partial ownership of.

Neumann also patented the word “We” through WeWork’s parent company We Company. He then charged WeWork—which he was CEO of—just shy of $6 million to use the word “We,” in a brazen example of self-dealing. And, it came to light that WeWork’s projected market for shared office space was insanely optimistic. WeWork claimed something like a $3 trillion potential. But it counted every employee in the United States who worked at a desk in cities where there was a WeWork as potential members. Every person with an office job in a non-U.S. city with a WeWork was counted as a potential member.

WeWork tried to make an initial public offering of shares in August of 2019. But, by September, it had gone bust, as WeWork’s numerous issues mounted. Neumann voted himself out of his CEO job, and gave majority control of WeWork’s stock to SoftBank. In return for his shares, SoftBank reportedly gave Neumann a $1B offer, a $185M “consulting fee,” and $500M to pay off a loan from JPMorgan. Neumann is a crazed capitalist’s wet dream. He “failed up” time and time again at the eventual expense of about 2,400 laid-off employees, until someone handed him $1B to go away.

Anyway, here I am: late January, in a post-Neumann WeWork, across the street from Bryant Park in New York City. The front of the building is canvased in scaffolding, but a semi-circular sign denotes the WeWork logo. WeWork’s attractiveness to investors has faded, but new opportunities always lurk on the horizon. The one on display today is psychedelics. After picking up my name tag from a woman who greets me with, “Welcome to the mushroom space, man,” I ascend the spiral staircase and enter the ballroom through a large pair of curtains.

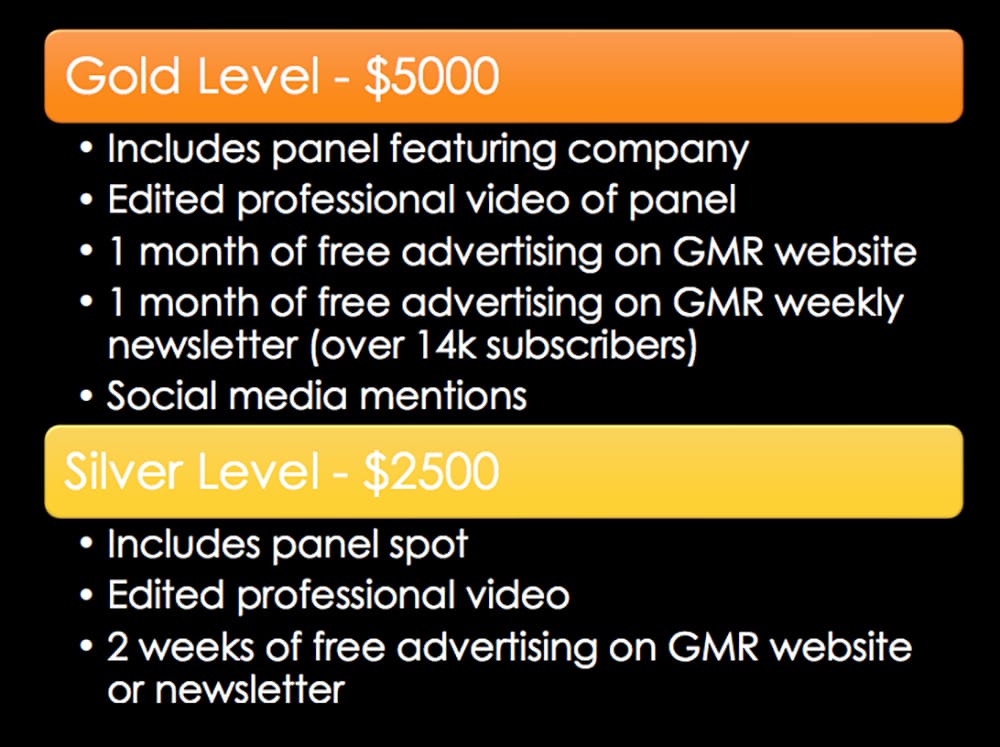

Toward the end of the fourth panel discussion of the day, Debra Borchardt—the CEO of Green Market Media and organizer of the summit, where speakers paid up to $5,000 to speak on behalf of their own companies—stands up from her laptop.

Ex-cannabis-pharma-executive-turned-psychedelic-investor-slash-also-a-gold-dealer Ronan Levy, his public relations manager Lewis Goldberg, and corporate cannabis consultant Brian Quigley, had been discussing the parallels between the early days of the cannabis industry and the current psychedelic investing scene.

“I have a question,” Borchardt says. She explains that, while putting together this summit, she has been approached by people about why she would support capitalist endeavors in the psychedelic space.

“And I thought, ‘Well, you know, it is biotech.’ And, we have had this same discussion in the biotech world of, ‘Why are you charging so much for this drug,’ without thinking of all the trials and how expensive it was,” Borchardt says. “I won’t get into drug costs and all that, but it seemed to me a repetitive argument. Do you guys face this with your companies? Do people address this to you and accuse you of being too capitalistic?”

To set the record straight, many Big Pharma companies actually spend more on marketing than research and development. A report from the California-based Institute for Health and Socio-Economic Policy found that in “2015, out of the top 100 pharmaceutical companies by sales, 64 spent twice as much on marketing and sales than on R&D, 58 spent three times, 43 spent five times as much and 27 spent 10 times the amount.”

To hear concerns about the negative effects of capitalism described as a “repetitive argument” felt dismissive to me, especially from a career financial journalist. Borchardt has been a contributor to Forbes and worked for the economic news site The Street throughout the 2008 financial crisis. Doesn’t she know what capitalism looks like? Even if we set aside the slavery and genocide that drove the primitive accumulation of capital, the ongoing cycles of boom and bust within modern, late-stage capitalism—alongside the exploitation and extractivism necessary to keep the whole system running—should be enough for any serious journalist to recognize the systemic problems inherent to this economic model.

She did tell the room at the beginning of the panel that she is a “real OG” when it came to cannabis and psychedelic market coverage, though. Her cannabis coverage dates way back to the year 2013. So, maybe I’m the weird one. I wanted to see how the capitalists on the panel felt about this question.

Levy has already gone on the record about the divided opinions regarding approaches to psychedelic capitalism, while giving an interview about his for-profit research and investing company Field Trip. He told Psychedelic Times that both nonprofit and for-profit psychedelic efforts are worthy of support, but that all parties need to work together, until we “get across the line.” Once we get across this metaphorical finish line, “more thoughtful conversations of how to respect the sacred aspects of psychedelics and original cultural values can be engaged in a much better way.” Too much infighting in the early stages, he claims, could stall the momentum of the industry.

Read: Let us develop a profitable corporate framework for these medicines. You know, one that will likely make it impossible for nonprofits to meaningfully participate. Once that’s in place, and we know that dissenting opinions can be easily squashed, we can start having these conversations.

From his seat at the front of the WeWork ballroom, Levy shrugs nonchalantly, admitting that, “I mean, the [capitalism] question has come up a couple of times.”

He assures the room that he takes a “conscious” approach to these issues, and he knows people have differing perspectives. He says he’s willing to have these conversations with anybody who wants to talk; but don’t think that means he will change his mind.

“We don’t always have good answers [when people criticize our approach], but we don’t want to shut down the conversations. So, it’s a dialogue. No system is perfect for achieving the ultimate societal goals. There are benefits and risks, and I’ll be the first to acknowledge that,” Levy says. “On balance, we think a for-profit, capitalistic approach to this makes the most sense, delivers the best incomes and the most outcomes to the largest group, and that’s where we land on this point. Doesn’t mean we’re right. It is just where our analysis leans.”

Quigley chimes in that, from his point of view, a balanced for-profit system can be achieved through having a diverse team on both the operating side and advisory council (hmm, again). He goes on to list that he has toxicologists, world-class scientists, mycologists, and a few other perspectives on his team—which actually sound like the typical people you’d have at one of these companies. These voices, he says, “can make sure that we are a for-profit entity, but also we are here to do good.”

For-profit or nonprofit, though, Levy told the crowd earlier in the presentation that all sides are on board with a capitalist, for-profit approach—for the most part.

“The truth is that most of the conversations we have had with the active participants in the nonprofit side of things, including MAPS and Usona, they get it. They 100% get it. They are not opposed to it [for-profits in the psychedelic space],” Levy said. “The pushback tends to come from more the community and the activists, who have problems with for-profit approaches.” However, Usona affiliates have pushed back on these types of claims through various public channels.

MAPS and Usona, for the uninitiated, are two nonprofit players in the psychedelic space. MAPS—or the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies—has been pushing to legalize psychedelics since 1986 and is conducting Phase 3 clinical trials for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD. And for the most part, MAPS’ executive director Rick Doblin says Levy’s claim is correct. Doblin is not inherently opposed to for-profit investors in psychedelic medicine and sees for-profits as a sign of the success of nonprofits who have been working to gain regulatory approval and public support for psychedelics for years.

Doblin regularly encourages for-profit investors in psychedelic spaces—just not his psychedelic space. “No private investment is accepted,” reads a bulletin about MAPS’ own for-profit arm, the MAPS Public Benefit Corporation. Even though Doblin clearly recognizes the dangers investors pose when it comes to MAPS, he claims for-profit investment in other companies is, “just an inevitable part of the mainstreaming process.”

“All that said, I don’t mean to imply that I think all psychedelic investments make sense or are likely to make any money for investors. I also worry that for-profit incentives will warp psychedelic medicines in similar ways to the way for-profit incentives have warped US healthcare, in particular. And international healthcare, though less so,” Doblin said in an email. “For example, I believe that esketamine for depression would be more effective if combined with psychotherapy. But, that would likely result in fewer administrations of esketamine and more psychotherapy sessions for preparation and integration, making less money for [Johnson & Johnson], but being better for patients. I’m also concerned that for-profit incentives might result in opposition to drug policy reform efforts.”

Doblin offers a sobering point here, albeit one that appears at odds with his past words and actions. When asked in 2018 if it mattered who was on the boards of for-profit psychedelic companies, he told Psymposia that having people like Johnson & Johnson alumni and regulators on for-profit psychedelic pharmaceutical boards would give him more confidence that they’d succeed in medicalizing these drugs.

It remains to be seen what, if any, effort MAPS will make to prevent the issues Doblin now acknowledges. MAPS has been one of COMPASS Pathways’ biggest advocates, supporting COMPASS’ decision to patent psilocybin synthesis methods, defending an exclusivity agreement between COMPASS and a psilocybin manufacturer (which prevented researchers from obtaining the psilocybin necessary for conducting clinical trials), and sharing data and regulatory connections with COMPASS.

Usona Institute, a nonprofit which is working on developing psilocybin for medical treatment, was one of the parties set back by COMPASS Pathways’ exclusivity contract. Speaking on behalf of himself (although he is one of Usona’s board members and a board member and President of the Heffter Research Institute), Carey Turnbull, told Fortune that—while he doesn’t consider himself an anti-capitalist—he does feel like COMPASS’ actions are an attempt to block competitors.

“COMPASS has shown almost no creativity. Their pitch sheet says, essentially, we’re going to establish exclusivity and make billions. But they’re entering a field that has been extensively researched by others,” Turnbull told Fortune.

In the Q&A following the panel in the WeWork, an audience member tells a story of his 15-year-old son who recently attended a Bernie Sanders rally, and came back saying, “Dad, I know what you’re doing has to exist within a for-profit structure. But don’t worry, because once Bernie wins, he is going to make sure we have some regulation around this stuff.” After a big laugh from the rest of the attendees, he continues, “I think it’s a good point, because I don’t think you can ever fully trust businesses, in the end.”

Panel moderator Goldberg—Levy’s PR manager—cuts in at this point, jerking a thumb at Levy. “I trust him, though,” he says, with a disarming smile. The audience member catches on and responds that, “Oh, of course I trust him, as well.”

Another audience member suggests that we should be giving back to and making space for the indigenous and spiritual communities who have been exploring these compounds for centuries before venture capitalists got involved. Levy admits that he is not, at this point, particularly concerned with issues like giving back or “sacred reciprocity.”

“From our perspective, we are focused on healthcare outcomes,” Levy says. “Our immediate focus, now and when we give back, is to make sure that we are creating pools of money and capital, but make sure that we can make these treatments—which are not inexpensive—available to more people. The marginalized people who might be excluded from accessing this care, because it is going to be expensive. It is very high touch point. So, I don’t have a great answer in terms of addressing the sacred reciprocity, but our focus, in terms of our commitment, is on patient outcomes and making sure people get access to clinical care.”

There is a lot of this talk from presenters—discussing the idea of making this expensive treatment (which they will be dictating prices for) more accessible. What isn’t discussed is the fact that mushroom treatment—in the context that I, and probably most of the presenters, investors, and audience members have experienced it—is extremely inexpensive.

An earlier presenter mentioned that magic mushrooms send the fewest number of people to the emergency room of any drug. And, they grow on cow shit, or brown rice flour, or rye grain, or wild bird seed, or a variety of other mediums that home-growers can easily procure. Yet, it is apparently of vital importance that we invest hundreds of millions of dollars researching entirely new ways to synthesize them, manufacture them, engage with them, and create a new industry for “the straights”—as Levy’s PR manager, Goldberg, calls them—to profit from.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Russell Hausfeld

Russell Hausfeld is an investigative journalist and illustrator living in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism and Religious Studies from the University of Cincinnati. His work with Psymposia has been cited in Vice, The Nation, Frontiers in Psychology, New York Magazine’s “Cover Story: Power Trip” podcast, the Daily Beast, the Outlaw Report, Harm Reduction Journal, and more.