Eleusis Benefit Corp: Taking the “Psychedelic” Out of Psychedelics

Shlomi Raz, CEO of Eleusis Benefit Corporation, made false claims about psychedelics. We asked multiple ethnobotanists, a medical anthropologist, and a chemist if they could help us set the record straight.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

As debates about the future of psychedelic legalization begin to appear in mainstream publications, the core message of would-be psychedelic profiteers is crystalizing into an all-too-Trumpian slogan, “Make psychedelics boring again.” The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is attempting to develop psychedelic analogues without “significant side effects” (e.g. “the trip”), while unethical entrepreneurs hype microdosing schemes through the BBC. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that corporate actors and military strategists are seeking to strip out the visionary (read: psychedelic) components of psychedelic experiences. After all, psychedelics have long been hailed as potential catalysts of revolutionary, countercultural change; hardly the ideal marketing narrative for consumer products intended to perpetuate industrial capitalism, or the status quo of US militarism.

The rebranding of psychedelics from “psychedelics”—literally, “mind-manifesting” visionary compounds, capable of catalyzing insight and resistance to dominant culture—into sub-perceptible “microdoses” marks a clear attempt at mainstream recuperation of these potent countercultural tools. As author and media theorist, Douglas Rushkoff, observed nearly 20 years ago, “Since the 1960s, mainstream media has searched out and co-opted the most authentic things it could find in youth culture, whether that was psychedelic culture, anti-war culture, blue jeans culture…they’ll look for it and then market it back to kids at the mall.” As proponents of psychedelic mainstreaming and medicalization disseminate revisionist histories to justify their approaches, we are observing the transformation of psychedelics into market commodities in real time.

Enter Shlomi Raz, CEO of Eleusis Holdings Limited (also known as Eleusis Benefit Corporation), a for-profit pharmaceutical company focused on, “Unlocking the anti-inflammatory potential of psychedelics.” In a recent opinion piece for STAT, Raz attempts to extend the “micro-washing” of psychedelics beyond the current fad of self-improvement supplementation and bring it into a fully-medicalized, pharmaceutical context. To this end, Raz concocts an all-encompassing, neocolonial narrative of “traditional” microdosing; a creation myth that sets the stage for Eleusis to pretend that it’s part of some long-standing psychedelic lineage of microdosing. In reality, Eleusis is just a pharmaceutical company looking to market a variety of low-dose psychedelic medicines, including LSD and 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI), a psychedelic phenethylamine first synthesized by Dr. Alexander Shulgin, and later Dr. David Nichols.

Raz briefly discusses scientific studies of higher-dose psilocybin, LSD, and ayahuasca experiences before casually stating that, “These high-profile research findings have obscured the primary traditional use of these medicines — as imperceptible anti-inflammatory agents.” Raz makes no attempt to identify any specific cultures or substances here; implicitly lumping all “traditional” practices with all psychedelics into a monolithic notion of “primary traditional use.” He then takes this neocolonial homogenization one step further by asserting (without evidence) that this, “primary traditional use,” was, “as imperceptible anti-inflammatory agents.”

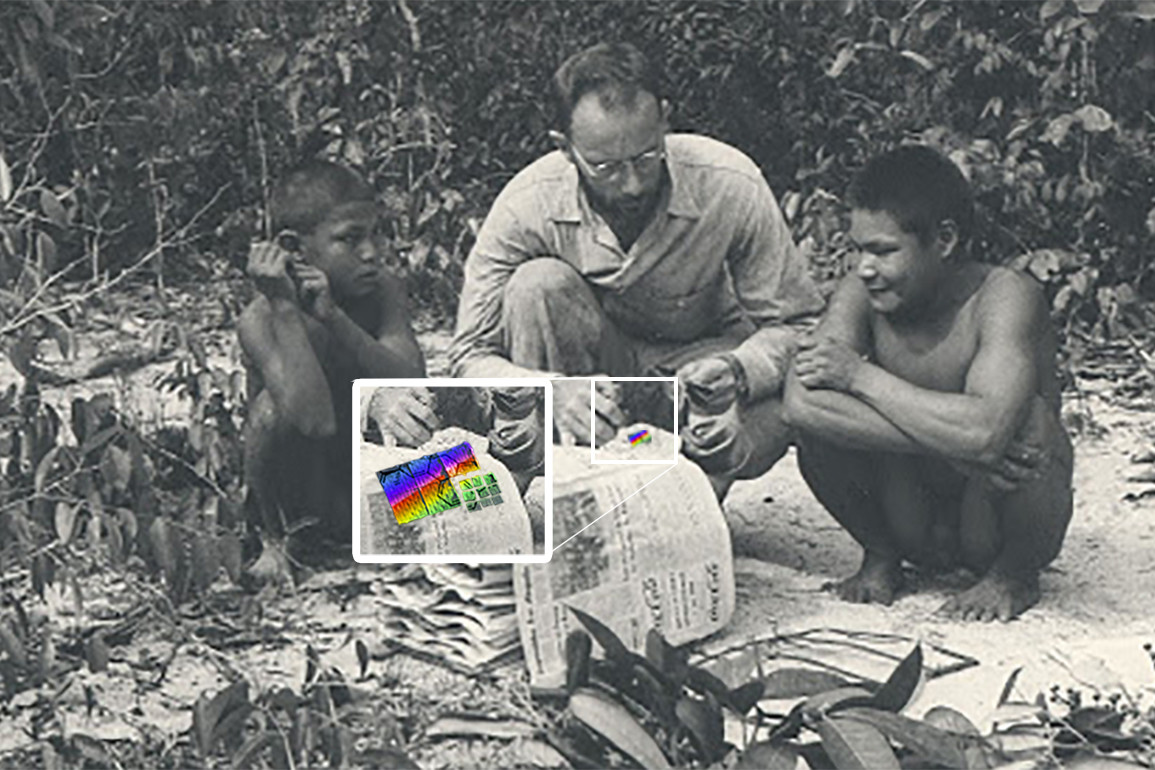

Given the varied ritual and medical ethnobotanical applications across cultures that ingest similar psychedelic preparations—to say nothing of the widely-varied traditions between cultures that use different psychedelic preparations—Raz’s assertion of a singular “primary traditional use” of psychedelics fails even the most preliminary sniff test. One need only skim through ethnobotanical reference works, such as Garden of Eden, by Snu Voogelbreinder, The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants, by Christian Rätsch, or Plants of the Gods, by Richard Evans Schultes and Albert Hofmann, to understand how nonsensical this claim is.

That’s not to say that the research side of Eleusis is entirely without merit. The investigation of LSD for Alzheimer’s disease is certainly intriguing. Furthermore, exploring the potent psychedelic, DOI, for use as an anti-inflammatory agent is absolutely fascinating. In 2012, Dr. David Nichols shared the story of how his son, Dr. Charles Nichols (now employed as Eleusis’ lead scientist), discovered the surprising anti-inflammatory potential of DOI. The story of this discovery appears to present yet another case of psychedelic serendipity, and the science behind the treatment itself may be truly revolutionary. However, there’s an incredibly important distinction to make between finding anti-inflammatory applications for substituted phenethylamines and fabricating wholesale narratives about “the traditional use” of psychedelics.

When reached for comment as to Raz’s claims, Dr. David Nichols replied:

“I don’t believe that the ‘primary traditional use’ of psychedelics was as ‘imperceptible anti-inflammatory agents.’ Nevertheless, it is true that all the claims for antidepressant, anxiolytic, and anti-addictive properties for psychedelics have relegated the anti-inflammatory properties of psychedelics to the shadows; almost no one is aware that they are potent anti-inflammatories.”

To be clear, there are bodies of folk knowledge and peer-reviewed papers documenting anti-inflammatory applications of psychedelics. However, Raz didn’t merely lament a lack of public awareness regarding the anti-inflammatory potential of psychedelics; he asserted that “imperceptible anti-inflammatory” applications were the “primary traditional use” of psychedelics. In light of the readily available ethnobotanical information—or the fact that he could have simply consulted the father of his lead scientist—it’s hard to overstate the absurdity of Raz’s generalized, sweeping assertion.

“This subject merits some actual study rather than trying to somehow force fit it with microdosing.”

Even the paper that Raz cites in his STAT article, The Appeal of Peyote (Lophophora Williamsii) as a Medicine, doesn’t contend that peyote’s main application was as an “imperceptible anti-inflammatory agent.” Additionally, Raz misrepresents his source, claiming:

“Eighty years ago, the renowned Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes wrote that the use of low-dose peyote was ‘centered around the therapeutic and stimulating properties of the plant and not around its vision-producing properties…Some of the ills listed as responding to peyote were tuberculosis, pneumonia, scarlet fever, intestinal ills, diabetes, rheumatic pains, colds, grippe, fevers, and venereal diseases…It is used as a white man uses aspirin.’”

This quote is disingenuous on several levels and comprised of sentence fragments pulled from two separate sections of the paper in question. Most significantly, none of the sentences that Raz has spliced together offer comment on “low-dose peyote.” Furthermore, the list of ills is in the context of groups who, “rely on the cactus as a panacea,” and for whom, “there is hardly a disease which is not believed to be curable with peyote.”

That said, the paper does discuss observations of indigenous people eating, “one [button] between meals as a sort of appetizer,” and the fact that, “Several mescal buttons are given three times during childbirth among the Kiowa, Kickapoo, Shawnee, and probably other Plains tribes.” While the paper discusses “therapeutic,” “pseudo-therapeutic,” “medical,” “medico-religious,” and “superstitious” applications of peyote, at no point does it discuss “imperceptible anti-inflammatory” peyote regimens as “the primary traditional use.” In other words, the only work Raz actually cites for his claim simply doesn’t support it.

Psymposia reached out to a number of experts for comment on Raz’s article. We received replies from six ethnobotanists, all of whom expressed skepticism about Raz’s claim. Two of them declined to comment publicly. However the other four offered the following remarks.

Keeper Trout, noted cactus expert, ethnobotanist, and independent researcher, said:

“As for the long-time use of peyote as an analgesic and anti-inflammatory this was, and still is, something involving its topical application and is doubtful that it is related to the low level of mescaline. Ariocarpus fissuratus and A. kotschoubeyanus are both used similarly to peyote as a topical liniment for rheumatism, joint pain or pain resulting from blows or bruises. As far as I am aware, mescaline is the only psychedelic in the peyote plant and it does not occur in Ariocarpus species. This subject merits some actual study rather than trying to somehow force fit it with microdosing. Most medicinal applications of peyote involving ingestion for treating illnesses, such as Schultes mentioned, are at fully active dosage levels. It is also noteworthy Schultes was simply summarizing what he had come across and did not vouch for peyote’s efficacy in those applications.”

Snu Voogelbreinder, ethnobotanist and author of the aforementioned, Garden of Eden, one of the most comprehensive ethnobotanical reference books available, stated:

“That is indeed an odd thing for Raz to say…it appears he has applied some therapeutic uses of peyote as though all psychedelic plants have those common uses – and I’d say those uses for peyote are not as common as suggested, because it is not plentiful enough in the wild. Maybe a long time ago there was enough of it growing that people would use it for all those minor ailments and still be sustainable harvesters, but I think numerous other medicinal plants would be used for such minor complaints in most cases. Without doubt, peyote’s spiritual uses have far greater cultural importance, as would be the case for any other visionary plant. Any other medicinal properties are a bonus – there are plenty of non-visionary plants that have such therapeutic effects…”

Dr. Glenn Shepard, ethnobotanist, medical anthropologist, and Emmy-Award-winning documentarian, commented:

“It is indeed true that visionary plants often have myriad other cultural uses and physiological effects, sometimes confirmed in bioassays, that are incorporated into holistic concepts of healing in indigenous medical systems. The Western obsession with psychoactive experiences has often eclipsed our understandings of such nuanced and multifaceted uses of plant medicines. However to assert, in broad terms, that a specific property (in this case, low dose anti-inflammatory response) is the primary use of ‘psychedelic medicines’ is to take such a corrective gesture to the opposite extreme, once again doing disservice to complex and holistic indigenous notions of health, healing and medicine.”

Dr. Constantino Manuel Torres, ethnobotanist and archeologist known for his extensive research into the Taino use of Anadenanthera snuffs, replied:

“To state that ‘the primary traditional use of [psychedelic] medicines — as imperceptible anti-inflammatory agents,’ is not correct. The statement is contradictory in itself: a primary use that is imperceptible(?).”

These replies offer significant evidence as to Raz’s lack of ethnobotanical credibility. But what about the other substances he discusses, such as LSD? Whether we situate “traditional” North American LSD use within the context of MK-ULTRA, The Diggers, The Merry Pranksters, The Grateful Dead Family, or any of the more discrete cultural movements associated with it, nowhere do we see a, “primary traditional use,” of LSD as an, “imperceptible anti-inflammatory agent,” quite the contrary.

Ken Kesey inquired, “Can you pass the acid test?” Jimi Hendrix asked, “Are you experienced?” Nick Sand heard a voice tell him, “Your job on this planet is to make psychedelics and turn on the world.” None of them were referring to “imperceptible anti-inflammatory” doses of LSD, not even close. Kesey—hardly alone in his assessment of LSD as being an incredibly powerful catalyst for personal and societal change—observed:

“I believe that with the advent of acid, we discovered a new way to think, and it has to do with piecing together new thoughts in your mind. Why is it that people think it’s so evil? What is it about it that scares people so deeply, even the guy that invented it, what is it? Because they’re afraid that there’s more to reality than they have ever confronted. That there are doors that they’re afraid to go in, and they don’t want us to go in there either, because if we go in, we might learn something that they don’t know. And that makes us a little out of their control.”

“In this role Shlomi helped pioneer the use of derivatives, both as weapons of mass financial destruction, as well as for the betterment of mankind.”

In discussing Raz, it’s worth examining how he presents himself. His biography, as published alongside a (now-deleted flickr page for a) talk he gave at the President Street Forum, entitled, “Game Theory and Brain Washing – A Practitioner’s Guide,” read:

“…In 2003 he left JPMorgan and joined Goldman Sachs, rising to Managing Director responsible for Structured Product marketing. In this role Shlomi helped pioneer the use of derivatives, both as weapons of mass financial destruction, as well as for the betterment of mankind. In December 2008, Shlomi received notice that he was the target (amongst many others) of a Department of Justice investigation into Anti-Trust practices relating to work at JPMorgan…and like the A-Team, has gone underground, surviving as a soldier of fortune.” [hyperlink added for reference]

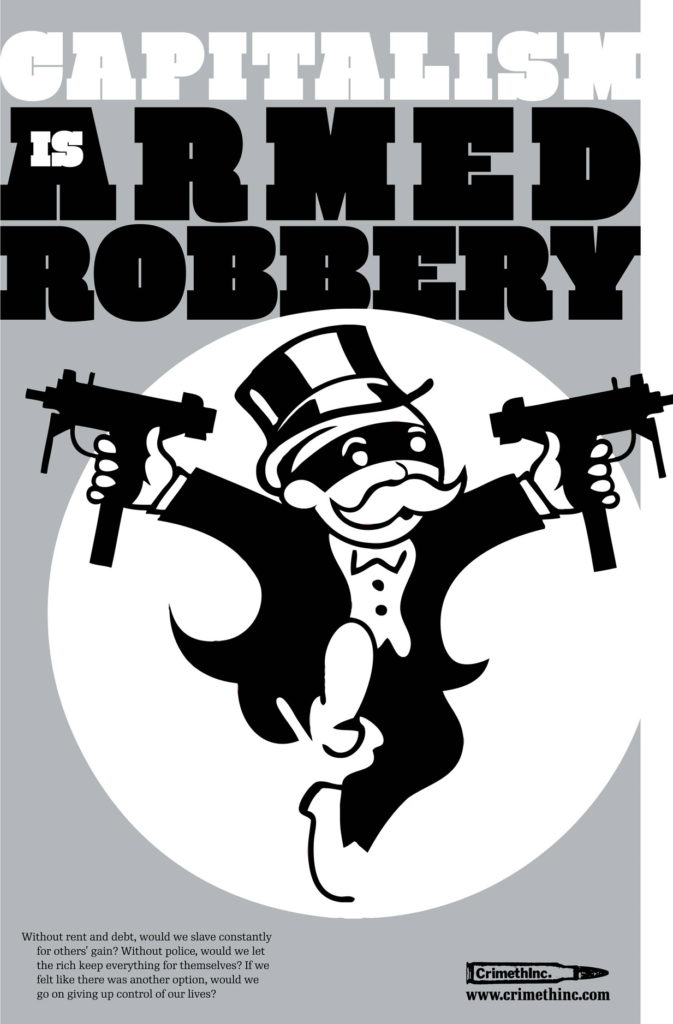

As such, we should understand Raz to be intimately acquainted with and fluent in the structures and systems of speculative capitalism. So, why has this self-professed mercenary taken such an interest in psychedelic pharmaceuticals? If we consider his bankster background, the current speculative investing in psychedelic medicines, and the fact that his company stands to benefit financially from his (false) narrative about “traditional use,” the answer seems clear: it’s a cash grab. Micro-washing the ethnobotanical record in order to create new markets for Eleusis’ products appears to be a ploy to enrich both Raz and his company.

Psymposia reached out to Raz multiple times for comment, but received no reply.

Regardless of industry, personal resumes matter: they offer insight into professional competence, ethics, and in many cases, philosophy. Just as with former Eleusis collaborator and COMPASS Pathways founder, George Goldsmith—whose past work at McKinsey & Co should raise eyebrows—Raz’s gloating about his role in creating, “weapons of mass financial destruction,” should give even a casual observer pause. It’s not that financial players have never been part of the modern psychedelic scene; quite the contrary. It’s that these capitalists—going back at least as far as JP Morgan executive and amateur mycologist, Gordon Wasson—have been demonstrably ruinous to psychedelic cultures, whether indigenous or industrial. Furthermore, in his STAT article, Raz has demonstrated a clear lack of credibility through his self-serving, mythical narrative.

Snu Voogelbreinder elaborated:

“Some people may need a human therapist to assist with [visionary psychedelic experiences], others may not, but I believe it’s a mistake to see these compounds as drugs that must be made ‘safe’ to use by the standards of societies that fear them. Rather, societies need to adapt themselves to embrace and understand these substances and the states they induce, so that we can get the most out of them, healing not privileged individuals who can afford treatment, but anyone who needs them. Psychedelics can help us with so much more than mere depression and inflammation-related illness. Raz and company wish to make psychedelics ‘mainstream and boring again,’ as if they were ever that to begin with. Psychedelics might become mainstream, but never boring, even if some researchers choose to ignore their full import.”

As Shlomi Raz, Paul Austin, and even researchers such as Dr. Charles Nichols cry out to, “Make psychedelics boring again,” we must recognize that these reactionary impulses stem from a self-interested, capitalist logic of personal profit. Commodification requires such mass-marketing ploys to depoliticize substances long-hailed for inciting recognition of our fundamental interconnectedness.

The greatest good psychedelics can offer may reside in catalyzing visionary insight into alternative sociopolitical systems and inspiring collective action, not enriching shareholders through peddling pharmaceuticals aimed at treating the symptomatic fallout of our increasingly toxic environments. This potential requires coherent historical and sociopolitical analyses through which to apply psychedelic insight, rather than simplified narratives aimed at mainstreaming.

Micro-washing psychedelics to render them palatable, profitable, and impotent for anything beyond individually-focused therapies obscures an invaluable lens for confronting the realities of skyrocketing socioeconomic inequality, government-sanctioned ecocide, and a doomsday clock creeping ever-closer to midnight.

Despite a few dealers, psychedelics have never been about profiteering. Despite their long-standing integration into some cultures, psychedelics have never been boring.

.

.

.

Perhaps instead of Humphrey Osmond’s, “To fathom Hell or soar angelic, just take a pinch of psychedelic,” Shlomi Raz would propose, To keep humanity asleep and snoring, make psychedelics plain and boring.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

David Nickles

David Nickles is an underground researcher and harm reduction advocate. He has presented social critiques and commentary on psychedelic culture and radical politics, as well as novel phytochemical data from the DMT-Nexus, at venues around the world. David’s work focuses on the social and cultural implications of psychoactive substances, utilizing critical theory and structural analysis to examine the intersections of drugs and society. He is a vocal opponent of the mainstreaming and commodification of psychedelic compounds and rituals, believing that such approaches inherently obscure the liberatory potential of psychedelic experiences.