“Acid Revival” portrays a resurrected scientific field, notably more conservative than its historic predecessor

Through candid interviews with modern psychedelic researchers, Danielle Giffort’s “Acid Revival” presents a profession obsessed with how it is perceived by mainstream audiences and desperate not to repeat the “mistakes” of the 1960s.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

In January 2019, psychedelics researcher Robin Carhart-Harris sat at the head of a small crowd at the World Economic Forum (WEF), a meeting of the world’s power brokers. Interviewing him was Alyson Shontell Lombardi, Business Insider’s Global Editor-in-Chief.

Shontell Lombardi asked the crowd if they’d ever consumed alcohol before. They responded with giggles. “Have you ever smoked cannabis?” was met with a more sober response. As she made her way up the illegal drug daisy-chain, the awkwardness intensified. When Lombardi asked about LSD—responding to the mood of the room—she uncomfortably slanted her mouth, waiting for the few responses from the crowd.

A lecture about psychedelic research at the WEF would have been unthinkable a few decades ago—maybe even a few years ago. Despite the crowd’s obvious discomfort, Carhart-Harris’ presence demonstrates a certain legitimization of psychedelics’ reputation within the “global elite.”

Based on anonymous interviews with 40 psychedelic researchers, sociologist Danielle Giffort’s book, Acid Revival, describes the concerted effort psychedelic researchers have put into laundering their reputations in their quest for this legitimacy. Giffort also describes how this goal is haunted by the spectre of Timothy Leary, the 1960s psychedelic researcher and countercultural icon. For modern researchers, he acts as a near-mythical figure, a cautionary tale which they strive to embody the antithesis of.

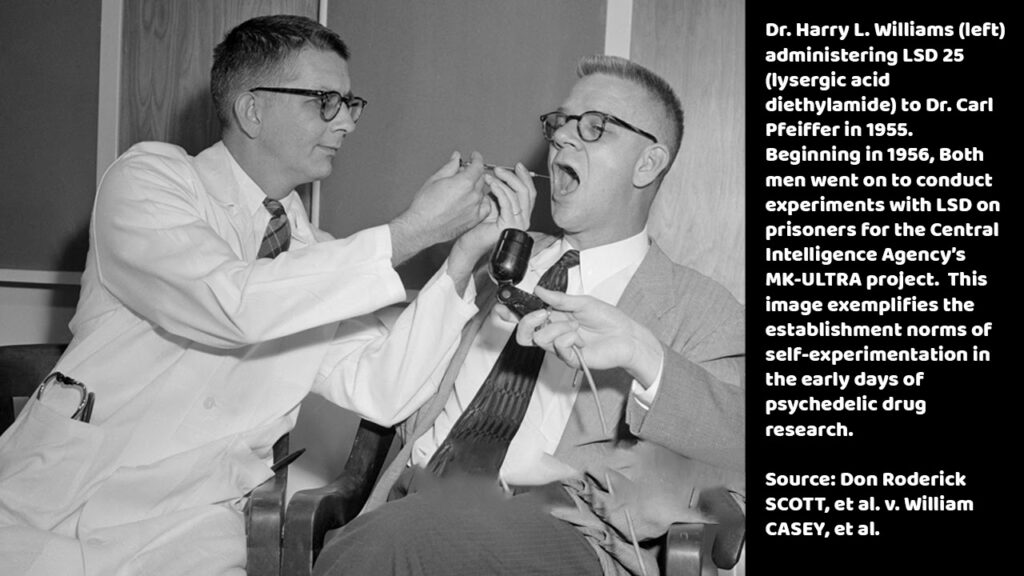

One common theme presented by researchers in the book is that Timothy Leary killed psychedelic research. They characterize him as an “impure scientist,” accusing him of failing to conduct objective scientific research, being too spiritual, and taking acid himself. In the first three chapters, Giffort explores each of these themes, places the accusations in historical context, and describes how modern scientists have—and, considering these are researchers who were somehow inspired to research criminalized drugs, often have not—changed.

In assessing what some have termed the “Leary’s Ghost fallacy” Giffort seems unconvinced by the “Great Man” theory of the death of mid-twentieth century psychedelic research. Instead, Giffort desensationalizes Leary and offers a cultural lens, pointing out that these complaints were endemic in the first generation of psychedelic researchers as a whole. She presents the decline of sanctioned psychedelic research as resulting more from changing scientific fashions than eccentric figureheads. For example, the rise in importance of randomized control trials (RCT) was not compatible with appropriately testing psychedelic drugs. Restraining a subject to a table, giving them LSD and leaving them unattended was not found to be therapeutic—who knew?

Importantly, Giffort explores how today’s researchers struggle with some of the same issues as Leary and his colleagues and, despite their criticisms, borrow much from this generation. Leary’s “set and setting” is still a notable part of psychedelic therapy and squaring it with RCTs is still difficult. However, this generation of researchers presents themselves as better at, or more willing to play “the science game.” They expertly frame research in ways that will appeal to the prestigious journals, the FDA, and the DEA, whose approval they need to conduct research. In doing this they build up a “performance” as “sober scientists”: spirituality is expressed in biological terms and if they engage in self-experimentation, they do not discuss it.

Dr. Roland Griffiths is frequently presented as a model sober scientist and psychedelics researcher. Griffiths is a pharmacologist with four decades of research to his name and a CV that includes over 380 publications. He left conventional drug research for psychedelics after experiencing states of consciousness which “seemed mystical” while meditating. Griffiths’ peers describe him as nerdy, boring, and square (they mean it as high praise). Colleagues can only speculate on whether he has ever taken a psychedelic drug. With his academic pedigree and his sober, detached aura, Griffiths offers a presentation that is ripe for framing as the antithesis of Leary. His performance is one that other psychedelic researchers strive to emulate.

Chapters four and five describe the lengths to which researchers go to cultivate this “sober” image. Suits and ties are an important uniform to make them indistinguishable from any other group of pharmacologists. When presenting in public, they screen fellow panelists so they are not associated with “someone with purple hair.” To accommodate researchers’ anxieties around disruptions to their performances, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) has implemented dress codes for other presenters and even volunteers. Established researchers also measure the performance ability of potential scientific recruits; those who are too self-aggrandizing or too excited about psychedelic drugs are filtered out.

While not historically accurate, the legend that Leary killed psychedelic research raises the stakes of this performativity for those who buy into it. After all, if psychedelic prohibition is (incorrectly) understood to stem from the antics of a single rogue researcher, such prophylactic performativity on the part of current researchers presents a misguided attempt to transcend prohibition through respectability politics. Interestingly, Giffort finds that some researchers who have read their history are ambivalent towards this narrative.

However, as with most cautionary tales, the historicity of the details is less important than the message: if one of us steps out of line, drifts too far from the sober scientist performance, sanctioned psychedelic research could die again. As a result, researchers send each other emails to monitor their behavior. They also worry over the actions of MAPS’ vocal and enthusiastic Executive Director, Rick Doblin, and have pressured him to adopt a more sober performance.

Acid Revival highlights the costs of the researchers’ policy of mainstreaming psychedelics. Trying to blend in with the middle-aged-white-male-dominated environment of pharmacological research has, predictably, turned psychedelic research into a boys’ club. Traditional psychiatry also has a heavily biased focus toward white communities; by emulating this field, researchers have heavily biased the focus of psychedelic research towards white communities, as well. Obsessively trying to maintain a squeaky-clean image has led to sexual harassment and assaults being swept under the rug. Unfortunately, we do not hear much of the researchers’ candid opinions about these criticisms. This feels like a missed opportunity, especially because many researchers are publicly silent on these issues and some researchers have actively worked to silence public discussions when asked to engage with them.

Unlike her subjects, Giffort is not conservative in her performance as an academic. She abandons the dry and sterile tones, the incomprehensible prose pregnant with technical terms, which litter many academic texts. Acid Revival is written with colloquialisms, with simple language, with personality. However, the lack of top-level formality does not detract from the presentation of her academic research. This is a revealing and informative book written to be read by anyone, which is not the case for all academic texts.

Overall, Acid Revival will appeal to those interested in psychedelic research past and present. The candid interviews the book offers makes it a unique source. Giffort convincingly uses these underexplored windows of insight to present a profession obsessed with how it is perceived by a mainstream audience and desperate not to repeat the “mistakes” of Timothy Leary, real or imagined. With regards to the “ghost” researchers’ construct of the man, Giffort concludes with one of Leary’s final declarations:

“You get the Timothy Leary you deserve. You get the Timothy Leary you earn. You create Timothy Leary in your own mind, and you’re in charge of it, like it or not. You can think I’m a madman, you can think I’m a thief, you can think I’m the greatest philosopher since Billy Graham and the Buddah. But it’s you that’s doing it.”

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Alex Brown

Alex Brown is the researcher, writer and producer of drug history podcast Hooked on History. He has a Master's in Contemporary History from the University of Edinburgh.