This is Part Two of “From Mining to Mushrooms,” a series exploring the infiltration of the psychedelic pharmaceutical industry by companies, investors, and executives from extractive industry. Read Part One and Three.

To read Psymposia’s interview with Thea Riofrancos, an expert on Latin American resource conflict, click here. For a long list of psychedelic-mining industry ties, click here.

“We accept it as normal that people who have never been on the land, who have no history or connection to the country, may legally secure the right to come in and, by the very nature of their enterprises, leave in their wake a cultural and physical landscape utterly transformed and desecrated. What’s more, in granting such mining concessions, often initially for trivial sums to speculators from distant cities, companies cobbled together with less history than my dog, the government places no cultural or market value on the land itself.”

-Wade Davis, excerpt from “Don’t sacrifice the Sacred Headwaters”

Extractive industry has a long history of problems, including failing to respect Indigenous land rights, widespread pollution, and practices that reflect the ongoing effects of imperial domination.

For a case study, let’s take another look at AIS Resources (AIS)—a Canadian mining and resource exploration company from which multiple executives have emerged to found psychedelic pharmaceutical start-ups.

[For more on AIS’ connections to psychedelic pharma, read From Mining to Mushrooms: As Psychedelics Enter the Mainstream, Mining Companies Look to Dig Up Profits]

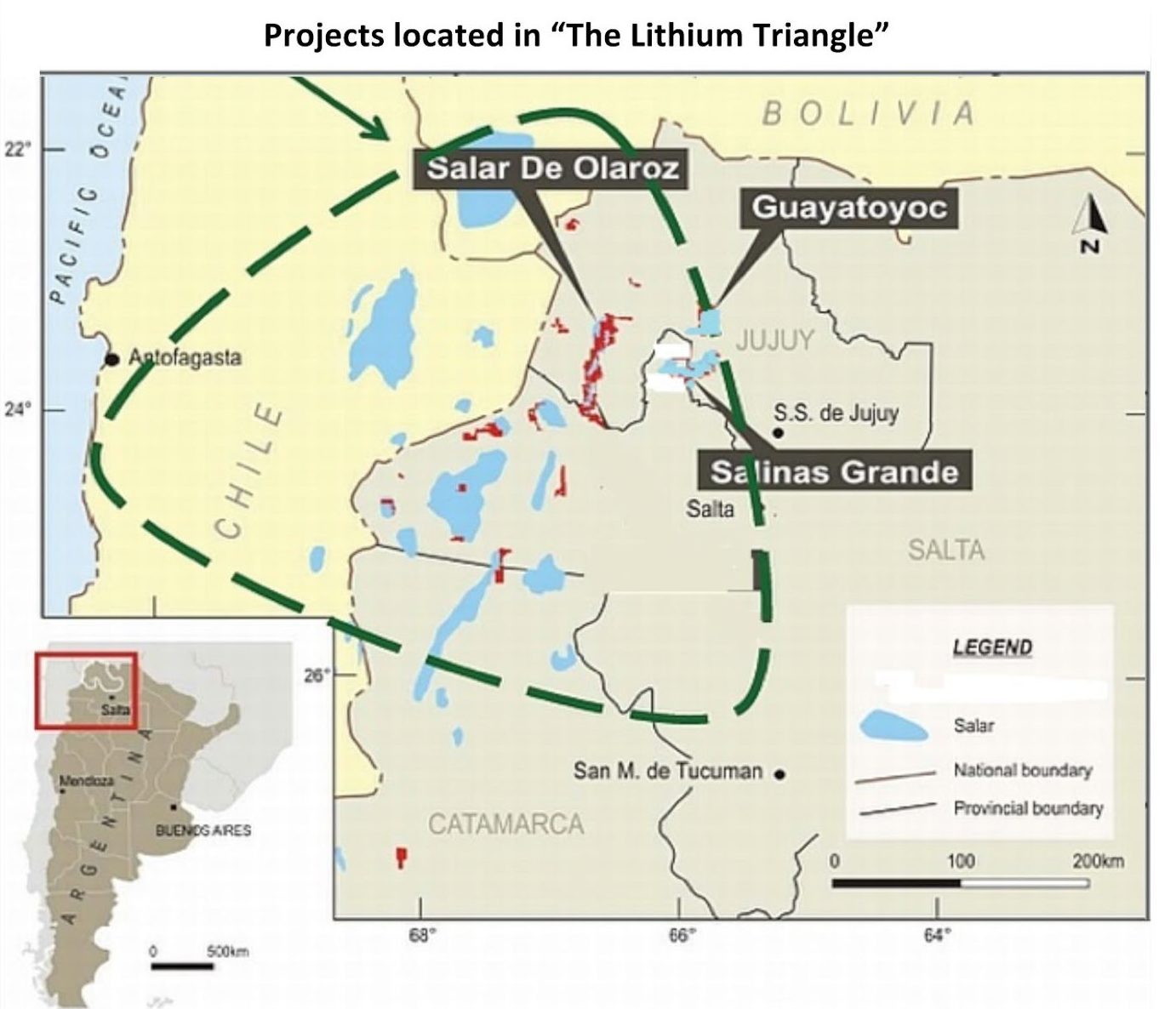

Besides mining manganese, the company has also boasted of their Guayatayoc Lithium Projects in the Jujuy Province (pronounced hoo-hwee) of Argentina—an area notorious for its dismissal of Indigenous communities’ rights in favor of mining projects.

Argentina—whose lax regulatory framework is appealing to foreign investors—has promoted mining as a pillar of its national economy for decades. As of 2019, the country was the fourth largest producer of lithium in the world. According to The Prior Consultation of Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Inside the Implementation Gap, the favorable regulatory framework in Argentina is based on the Argentine Constitution, which acknowledges that provinces “have the ownership of the natural resources existing in their territory;” the Mining Code of 1997; and Law No. 24,196 on Mining Investments of 1993.

“Both of the latter texts promote investment projects by international companies without any reference being made to the territories and Indigenous Peoples,” according to the aforementioned The Prior Consultation of Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Inside the Implementation Gap.

This document explains that, although lithium extraction is not as environmentally taxing as open-pit mining and non-conventional hydrocarbon extraction techniques, it does damage the environment. This is because lithium mining requires enormous amounts of water—a resource already scarce throughout the arid landscape of Northern Argentina—and chemical leakage can cause pollution. Lithium mining competes with the agricultural activities of local Indigenous communities and disrupts the autonomous functioning of people in territories with their own histories, practices, cultural significance, and dynamics of social organization.

The International Labor Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention of 1989, which was ratified in Argentina, provides guidelines for proper consultation of Indigenous peoples about land use. This convention—as a ratified international standard—should take precedence over national laws such as the Mining Code of 1997. However, governments and mining outfits often fail to properly meet these standards for consultation.

The Jujuy Province—where AIS has invested in lithium mining—and its neighboring Salta Province are home to the Kollas and Atacama Indigenous communities.

“These communities have been evicted from their lands and their rights violated since colonial times, and these actions have been repeated by the Argentine State,” according to The Prior Consultation of Indigenous Peoples in Latin America: Inside the Implementation Gap. The Kollas and Aracama communities have been fighting for their land for nearly a century. The document states that “at the beginning of 2010, when lithium was discovered in the underground brines that feed the salt flat in [Jujuy and Salta], multinational companies, the national government and the provinces of Jujuy and Salta undertook a rapid process of exploration in the area. This process was carried out under the notion of ‘development’ and triggered conflict with the Indigenous communities inhabiting their ancestral territories.”

The government of Jujuy declared lithium a strategic natural resource that could help generate socio-economic development in the province, which granted the Jujuy government a more interventionist position as a business partner in mining projects. This meant more money for the Jujuy government, but the Indigenous communities affected by the decision were granted little to no proper consultation.

In 2010, the Argentinian communities affected by these mining projects began meeting on a monthly basis and formed the Board of Indigenous Peoples of the Salinas Grandes Basin and Laguna Guayatayoc for the Defense and Management of Territory.

After their claims to the land were dismissed by Argentinian courts, the group took their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. This drew international attention to their struggle, and in 2011 the UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CESCR) expressed concern about the persistence of threats, violent displacements, and evictions of Indigenous peoples from their lands. CESCR stated that it regretted the “deficiencies in the consultation process with the affected Indigenous communities which have allowed the exploitation of natural resources in the territories traditionally inhabited or used by these communities.”

Jujuy Vialidad avanza sobre Comunidad Kerusillar sin Estudio de Impacto Ambiental, sin consulta previa libre e informada , arrasando con todo a su paso. Solicitan ayuda y difusion @gargantapodero @ArandaDario @Gatosylvestre @zlotomarcelo @odonnellmaria @Sietecase @nelsonalcastro pic.twitter.com/Xbc15shiIa

— Victoria Veracierto (@mavicvera) September 16, 2019

Following the influx of international attention to these issues, much of the exploration activity in the area around Salinas Grandes stalled out. And, in 2015, the 33 communities that make up the Board of Indigenous Peoples of the Salinas Grandes Basin and Laguna Guayatayoc for the Defense and Management of Territory came together to approve a document called “Kachi Yupi – Huellas de la Sal.” This document was meant to preserve their ancestral cultures through specifying the exact process for conducting the consultation and Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) process—which allows Indigenous communities to give or withhold consent to any project that may affect them or their territories.

In 2016, the importance of the “Kachi Yupi” text was acknowledged by the Argentine National Ombudsman—an institution within the national Congress—in a resolution which made a plea to several national and provincial authorities to respect these rights.

By 2019, though, the provincial government of Jujuy had already put out a new call for international bidders for mining prospecting and exploration in the area. The bidding process was carried out by Jujuy Energía y Minería Sociedad del Estado (JEMSE), a governmental entity which was created in 2011 by the government of Jujuy in order to participate in and profit from the surveying, prospecting, and exploration of hydrocarbon and mineral resources.

In response to this bidding process, the Indigenous communities banded together once again and directly protested the mining companies who received the bids: AIS and Ekeko S.A. (an Argentine lithium mining company which was originally funded by AIS’ Chief Chemical Engineer, Carlos Sorentino), according to the 2019 edition of “Conflictos Mineros en América Latina” and Tierra de Resistentes’ report, “White Gold: The Violent Water Dispute.”

AIS’ current CEO, Phil Thomas, told Psymposia in an email that he called police to the scene when he heard about the protests, calling the demonstrations “illegal.” Thomas said that protestors walked up and down the road, and to AIS’ drill site. He claimed that the protestors stole some firewood and let the air out of the tires on a backhoe, but did not do any other damage. In a Twitter post from February 15, 2019, though, Thomas wrote that he had all the protestors charged with trespassing and damages “which will be in the $10,000’s” and described the protestors as a “rent-a-crowd showing up from Jujuy.”

Pia Marchegiani, a director of the sustainable development nonprofit Fundación Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (FARN), said that the act of protest, itself, was not illegal, however if firewood was stolen or tires were deflated, this would constitute a small offense. Marchegiani said that throughout the protest there was tension between protestors and the governor of Jujuy, Gerardo Morales, who told the protestors that he was willing to speak with them only if they would come to him in-person. The community members rejected this offer, questioning why they should have to come to him—hundreds of kilometers away—when the issue they wanted to address was mining companies entering their land without proper consent. Governor Morales refused to meet them on their land.

¡El agua vale más que el #litio! Junto con las comunidades Kolla y Atacama del territorio de #SalinasGrandes y #LagunaDeGuayatayoc, presentamos una acción de amparo en la CSJN para prevenir el daño que provocará la #minería de #litio.

Mirá el comunicado 👉https://t.co/Oa3zF2Xf5y pic.twitter.com/PWQGT21W1R— FARN (@farnargentina) December 19, 2019

Thomas told Psymposia that, prior to this confrontation, AIS “did all the right things including more than 20 community consultations and the various presentations to the mines department and to the meeting of 14 representatives at the UGAMP [meeting on the environmental management of mineral exploration] in Jujuy.” Although many consultations seem to have been conducted, it does not appear that the majority of Indigenous communities affected had officially approved anything. According to FARN, these “community consultations” are often one-sided and do not allow for much engagement from communities.

Marchegiani told Psymposia that UGAMP meetings take place within the Ministry of Mining, where representatives from governmental agencies meet to discuss mining projects. Sometimes representatives from Indigenous communities are invited to get more information about mining projects. However, Marchegiani was very clear that this kind of consultation does not necessarily meet FPIC standards, which require governmental authorities to mediate consultations between companies and Indigenous communities in culturally appropriate formats.

“The whole reason the right to prior consultation even exists in international law, as well as in national constitutions, as well as in Latin America, is because of the trampling of territorial rights on the part of extractive firms,” said Dr. Thea Riofrancos, a political scientist whose research focuses on conflict over resource extraction in Latin America. “This right exists in order to avoid this situation. But, the problem is that this right—though many Latin American countries have it in their legal system—is not really properly enforced.”

Proper consultation can mean governmental authorities ensuring the presence of translators that can relay information to communities in their native languages, in an appropriately comprehensible manner, and making sure that communities are able to attend meetings. Marchegiani explained that the office in which UGAMP meetings are held, for example, is around 300 kilometers away from some of these communities—approximately a six-hour round-trip drive. Meetings are typically held during working hours, Monday through Friday. For most of the affected communities that farm or herd cattle, this presents challenges as their ideal time for meeting is on the weekends.

“It’s not flexible enough for many. Our experience is that this doesn’t offer the environment to properly discuss and to question impacts, and to say, ‘I don’t understand’…But, the government is not demanding this kind of dialogue,” Marchegiani said. “Our state, the local state, the provincial state, is not mediating this relationship. And, this is with companies that have a lot of resources and have people who are studying these communities to see how to approach them, and communities who are presented with complex information and environmental impact assessments, which they don’t understand. They say, ‘I don’t even know what kind of questions to have. I don’t get it at all.’ Imagine a bunch of technical information that most people wouldn’t understand either.”

Riofrancos elaborated on the power structure between multinational extractive companies and the communities whose land they hope to exploit.

“Any time you have very asymmetric power relations, like pretty low-income, ethnically-marginalized, Indigenous, and also mestizo—mixed Indigenous-European descent, which is some of the people in Argentinian communities—that are rural, that are isolated, that have suffered a lot of state and economic neglect—these are pretty marginalized actors, interacting with extremely well-financed foreign multinational firms…It’s a very asymmetric relationship and when you don’t have state public institutions that are good or willing to regulate those situations, then it results in all sorts of social and political problems,” Riofrancos said. “It might be a local politician being bribed by someone in order to get a permit, it might be [companies] investing in so-called ‘corporate social responsibility’ stuff where they might invest in building a soccer field in the community, but with the quid pro quo that the community doesn’t protest the water issues. That sort of stuff is extremely rampant in extractive sectors, in general, because of that asymmetry, and because of often the lack of state regulatory muscle.”

Thomas claimed that AIS had received permission from one of the communities in the area where they had hoped to exploit lithium. But, Marchegiani explained that this doesn’t necessarily mean much in an ecosystem that relies on a closed watershed, such as the one that supplies water to Jujuy and Salta.

“Obviously, a company could find and talk to somebody and offer something in exchange and there would be communities that would say yes [to these projects]. But, this is not the whole area. We are talking about a watershed that is integrated [and shared by many communities]. You cannot say, ‘OK, water you use up here doesn’t affect other communities,’ Marchegiaini said. “This is something that is tricky from the legal side because the authorities say, ‘Your company is interested in this certain area, whatever, this piece of land? Then you should talk to these two communities because these are their lands. But, not to the ones that are just outside because that’s not their land.’ But, because the water source is connected, the communities are saying, ‘We need to make a decision at the watershed level.'”

In December of 2019, the Kolla and Atacama communities of the Jujuy and Salta provinces, along with FARN, filed an environmental protection action with the Argentine Supreme Court. They argue that lithium extraction in the area will result in more water leaving the system than can naturally enter, and that other environmental concerns have not been properly evaluated.

“There are not enough environmental baselines studies produced at the basin level, nor are existing projects cumulatively evaluated together with other water uses. There is no comprehensive watershed vision, since both Salta and Jujuy authorities do not manage the basin in an interjurisdictional way. Furthermore, local communities have not been involved in decision making. Thus, it is unacceptable to move forward. It is irresponsible and an outrage,” said Santiago Cané, FARN’s legal area coordinator.

FARN and the communities involved have requested the suspension of all lithium mining activities, and of all permits pending, until appropriate environmental impact assessments are conducted and the basin is managed in an interjurisdictional manner.

“The projects need to be stopped before this damage is produced,” Marchegiani said. “We have this environmental principle, it is the ‘precautionary principle.’ We say, ‘Not having the right evidence or the right scientific evidence should not hinder you from taking protection measures.’ Even if you are not certain about the extent of the damage, you should act to protect the environment. This is the kind of argument we are putting forward.”

Tanks are full of water ready to drill tomorrow. Concrete was still a bit drying this morning at Salinas Grandes pic.twitter.com/R3ONH895NY

— Phil Thomas (@PhilAIS_Resourc) November 28, 2018

When questioned by Psymposia, AIS CEO, Phil Thomas, claimed that many environmental reports had been conducted, and cited reports conducted through consultants of AIS and other multinational mining companies. Marchegiani acknowledges this, but takes issue with the fact that there seem to be no impartial parties conducting these reports.

“A company hires a consultant that reports to them saying there will be some impact, but not a lot, because obviously they want their project approved. But there’s not any requirement for a third party review. This is what we are demanding,” Marchegiani said. “[Currently,] there are environmental reports made by those interested in having the project approved with an authority that is very much eager to get the projects.”

Thomas was steadfast that his company’s lithium extraction would not have a dramatic environmental impact in the area. (Note: It becomes increasingly difficult to take Thomas’s environmental safety claims seriously, though, as he has publicly stated online that he denies human influence on climate change. In response to a tweet on March 2, 2019 claiming that humans are contributing to climate change, Thomas wrote, “No it’s not human pollution…it’s paleo tilt and volcanoes!!”)

In an email, Thomas told Psymposia that AIS had planned to use the company Ekos Research’s “Ekosolve” solvent extraction process, which he claimed would return fresh water to the ecosystem.

“The process doesn’t need any evaporation ponds, has a small factory footprint and relies on chemistry of solvent extraction to take out the lithium chloride,” Thomas said. He claimed that this method would have “zero chance” of affecting groundwater and said that claims that it might have adverse effects on groundwater were “just ludicrous.” He cited testing of Ekosolve at University of Melbourne and “a Beijing university,” and said Ekosolve had been used for uranium extraction.

It should be noted here that Thomas’ other company—Panopus Plc—is a partner in Ekosolve, according to Thomas’ LinkedIn page. The only citation Thomas provided for Ekosolve’s supposed environmental efficacy was a PowerPoint presentation attributed to himself and an internal researcher with Ekos Research. Psymposia has not received a response from Thomas since asking him to elaborate on how Ekosolve is more environmentally-friendly than other methods of lithium extraction.

Other members of the lithium extraction industry questioned Thomas’ claims, though.

Ekosolve’s extraction process falls into the category of Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) techniques, which many in the industry are hailing as a “miraculous” new technique that will increase the amount of lithium that companies can extract in shorter periods of time. This process will allegedly produce a smaller environmental footprint.

Robert Mintak, the CEO of Standard Lithium Ltd., told Psymposia that these DLE techniques are emerging at a pivotal point in the history of lithium extraction. The techniques that the industry has used for the past six decades were not designed to meet the growing demand for lithium that is accompanying the adoption of electric vehicles.

“DLE has a number of advantages to solar evaporation: higher recovery, high-purity final product, scalable, faster. But, because it will require freshwater, chemical reagents, and power it may not be economic at every project which, at the end of the day, is what will determine if it is funded. DLE will play a significant role [in the future] but it is not a silver bullet,” Mintak said via email. “The argument around solar evaporation vs. DLE with regards to water loss or [water] consumed is far more complicated than clickbait headlines make you believe.”

Psymposia asked Alex Grant—a mining consultant at Jade Cove Partners—about Thomas’ claim that his DLE solution would not only have “no impact” on local water, but also return alkali-free fresh water to the ecosystem. Grant told Psymposia, “That appears to be a false statement and/or his technology will not be economic. I recommend not quoting this person in your article. He is likely not credible.”

Dr. Carlos Sorentino—Chief Chemical Engineer for AIS and a director at Ekos Research, which helped develop Ekosolve—told Psymposia that Ekosolve, like most DLE techniques, has not yet been commercially tested for lithium. With this in mind, any statements that AIS would have made during community consultations in Argentina about the environmental safety of using the Ekosolve extraction technique at a commercial level—while potentially true—would have been based on speculation and smaller-scale testing.

“It can’t be said definitively that DLEs have a lesser environmental footprint than traditional methods. Their environmental friendliness is a valid hypothesis that needs to be scientifically proven. I believe some (but not all) [of] the new DLEs are environmentally superior, but this assertion requires factual confirmation,” Sorentino said, contradicting his CEO’s assertion that Ekosolve presents “zero chance” of affecting groundwater.

Marchegiani noted that testing out hypotheses on South American soil is not unheard of for extractive companies.

“It is why they come to these areas and are not doing this in the middle of Canada or somewhere in the US. Remember that lithium is not a scarce resource. It is all over the world. It is just cheap to extract here,” Marchegiani said. “This is also why you have all these companies who want to try their techniques out here. It could be that they want to figure out if this works at a bigger production level. They have an investment they want to prove somewhere.”

(Note: Some DLE techniques are being tested in the US, such as Standard Lithium’s DLE demonstration plant in Arkansas. However, Mintak noted that his company lucked out through partnering with a pre-existing bromine extraction operation in the area, providing Standard Lithium with much of the necessary infrastructure from the project’s conception.)

It appears that the local communities and FARN may have ultimately deterred AIS from extraction in the area. A December 17, 2019 press release stated that “the Company has decided to relinquish the [Guayatayoc] option as the Secretary of Mines has made no progress toward arranging a UGAMP meeting, nor setting time limits on the discussion period for exploration programs.” But, “AIS will monitor conditions in Argentina with a view toward re-engaging operations when circumstances improve.”

“We left Argentina especially Jujuy province basically because of incompetence in running the administration process by [the Secretary of Mines] and we could not get permission to drill our next hole…It’s sad as I have spent more than 20 years working in Argentina but the administration has to face facts. No-one will follow us with real money. We are still recovering from our US$4m loss in Argentina,” Thomas said in an email, and added—somewhat condescendingly and unrelatedly—that, “the communities [in the Jujuy Province] are still suffering with employment, health, mental health and drug abuse issues,” as if AIS’ presence would have solved those issues.

Marchegiani told Psymposia that the Supreme Court of Argentina has yet to accept or reject the lawsuit which FARN and the Indigenous communities filed. But, she has seen that some companies, like AIS, have removed their investments in the area due to pressure from the local communities protesting extractive industry projects over the past decade.

“[The Indigenous communities near Jujuy and Salta] just say, ‘No, we don’t want you,’ Marchegiani said. “They’re so tired of being played with different promises. They say, ‘We don’t want lithium extraction and we don’t even want to get consulted about it. We just say no already.’ And, this is a consequence of not having public authorities do what they have to do when they should do it.”

The case study of AIS’ Guyatayoc lithium projects presents a number of questions and concerns about mining executives bringing their playbook to bear on the emerging psychedelic pharmaceutical industry.

Thomas’s exaggerated environmental safety claims to Argentinian communities whose environments will likely suffer from lithium extraction should give us pause and make us ask a few questions. Will psychedelic executives—especially those with backgrounds in mining and highly speculative industries—be inclined to misrepresent the effectiveness of psychedelic treatment options to uninformed consumers or vulnerable patients in order to rake in profits?

Should psychedelic pharmaceutical companies—which promote “wellness” and claim to heal trauma—be held responsible for the trauma or sickness they may be causing through their continued mining operations or other extractive endeavors?

With the cannabis bubble bursting in the rear view mirror, we should ensure that executives hopping from extractive industries into the nascent psychedelic pharmaceutical industry are well-scrutinized, and we should not assume or blindly trust that they will use tactics that are any less exploitative than those they used in their past career roles as mining executives.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Russell Hausfeld

Russell Hausfeld is an investigative journalist and illustrator living in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism and Religious Studies from the University of Cincinnati. His work with Psymposia has been cited in Vice, The Nation, Frontiers in Psychology, New York Magazine’s “Cover Story: Power Trip” podcast, the Daily Beast, the Outlaw Report, Harm Reduction Journal, and more.