How To Open Your Wallet: The Hyped and Distorted Claims of Online Psychedelic Marketing

From cultural appropriation to “Shroom Boom,” psychedelic online marketing gaffes and misrepresentations are becoming more and more prevalent from major psychedelic organizations.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

The budding psychedelics industry is full of individuals and organizations ideologically and financially invested in presenting the field as rooted in rigorous, buttoned-up science. However, the entrance of these drugs onto the mainstream stage has already spawned a number of questionable media and marketing stunts. These have included collaborations between psychedelic research groups and various “crunchy” businesses (such as Goop and Dr. Bronner’s); uncritical news segments on networks like Fox and CNN; and endless celebrity endorsements. One executive has even gone as far as claiming that psychedelic pharma will usher in a new “spiritualized humanity” by 2070.

More often than not, these approaches have oversimplified psychedelic science for the sake of an attractive narrative. But — over the last year or so — a number of online promotions from prominent psychedelic organizations have gone above and beyond, pushing the discourse even further from any kind of measured discussion, with results verging on parodying the cultures and science in which these drugs are rooted.

DoubleBlind Magazine claims to be an educational outlet with “a commitment to fact-checking,” proceeds to repackage and promote understudied science

Last year, I published a story through Psymposia about a billboard advertisement that DoubleBlind Magazine and a number of other wellness brands purchased together. DoubleBlind took to social media, boasting about it as the “first-ever billboard campaign in the U.S. devoted to plant medicines” that was “[disrupting] the profit-driven advertising we often see in places like Times Square to fuel a conversation about healing.”

Spoiler: It was not the first campaign of its kind and it was advertising products that DoubleBlind and its partners sold (just like any other advertising in Times Square).

At the end of that article, I made the argument that any outlet declaring that it provides the “most trustworthy information on psychedelics” and seeks to educate the public about growing and ingesting illegal drugs has a responsibility to its readers to uphold the highest standards of accuracy.

Since then, it has come to my attention that DoubleBlind charges hundreds of dollars for classes based around generally-disproven (and unproven) claims about microdosing for mental health, and information about psychedelics that could otherwise be found for free online.

For $399, DoubleBlind offers a “30-Day Live Microdosing Program,” taught by Adam Bramlage — a “microdosing coach” and founder of the company, Flow State Micro. The decision for the “most trustworthy” source on psychedelic information to sell a course on microdosing is dubious, considering the largest placebo-controlled trial on microdosing recently concluded that microdosing either a psychedelic or a placebo for cognitive enhancement provided essentially the same benefits.

“In the largest placebo-controlled trial into psychedelics to date, they found that small doses of LSD indeed boosted the psychology in all manner of ways,” Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian. “[But] when the researchers examined what trial volunteers took, they found placebos worked equally as well as the drug.”

Genuine question: As a journalistic outlet which claims to promote psychedelic education, how do you square selling microdosing classes with the growing body of research indicating no meaningful difference between microdosing and placebo for psychological improvements? https://t.co/HtK9VLSDbN

— Russell (@RussellHausfeld) February 17, 2022

DoubleBlind co-founder Madison Margolin has gone on record about microdosing’s lack of effect. On the CelebStoner blog, writer Steve Bloom reported that when “asked about microdosing psychedelics, Margolin scoffs, ‘Microdosing is the CBD of psychedelics. (It’s) for people who are afraid to get high. People do CBD and microdose for similar reasons.’”

DoubleBlind producer and host of the organization’s “How To Use Psychedelics” class, Zeus Tipado, has also written a number of articles noting that microdosing placebos seems to have the same effect as microdosing psychedelics (which generally cost a lot more than a sugar pill, especially when paired with $399 classes).

Tipado even seemed to acknowledge the issues of microdosing classes and coaching in a recent article, stating, “On social media, a potpourri of enticing microdosing courses are available. These often come with pricey memberships hovering around promises of ‘life improvement’ and ‘mental sharpening.’” DoubleBlind even offers a membership service called DoubleBlind+, which it describes as “a definitive resource online for psychedelic education and community building.”

Tipado concludes that article by stating that if someone feels like microdosing truly does help them, he is in no position to tell them to stop. But, he writes, “It would be equally dismissive for me to not inform you that the marketing claims of microdosing are severely misleading. Some are even downright false when compared to the current science surrounding it.” DoubleBlind advertises microdosing for Lyme disease and irregular periods.

Beyond selling classes on techniques that its own organization’s members seem skeptical of, DoubleBlind’s marketing may strike some as predatory.

Navigating DoubleBlind’s website, readers are bombarded with pop-up discount ads and offered “free” guides, which ultimately recommend buying classes. The “free” microdosing guide offer, for example, auto-redirected anyone who signed up for it to a $149.99 microdosing course.

Sigh…

Last month, I wrote about @doubleblindmag's billboard ad, which was marketed as a "first-ever" plant med destigmatization campaign. It wasn't.

Yesterday, I came across these ads for "free" guides which immediately redirect to a $149 class… 1/4#corporadelic pic.twitter.com/XoyL0pqrpk

— Russell (@RussellHausfeld) November 12, 2021

While writing this article, I scrolled through DoubleBlind’s class offerings and received an email almost immediately titled, “Get Our Free Microdosing Guide!” which began with the line, “I noticed you were checking out our course.”

During my scroll through DoubleBlind’s course offerings, I did not give them my email address or ask for a free guide, which begs the question: How did they “notice” I was checking out their course?

I asked DoubleBlind co-founder Shelby Hartman this question and she told me that I input my email months ago, on November 11, 2021 (when I originally signed up to receive the free microdosing guide via email) and that my “cookies are saved on [the] website for two years.”

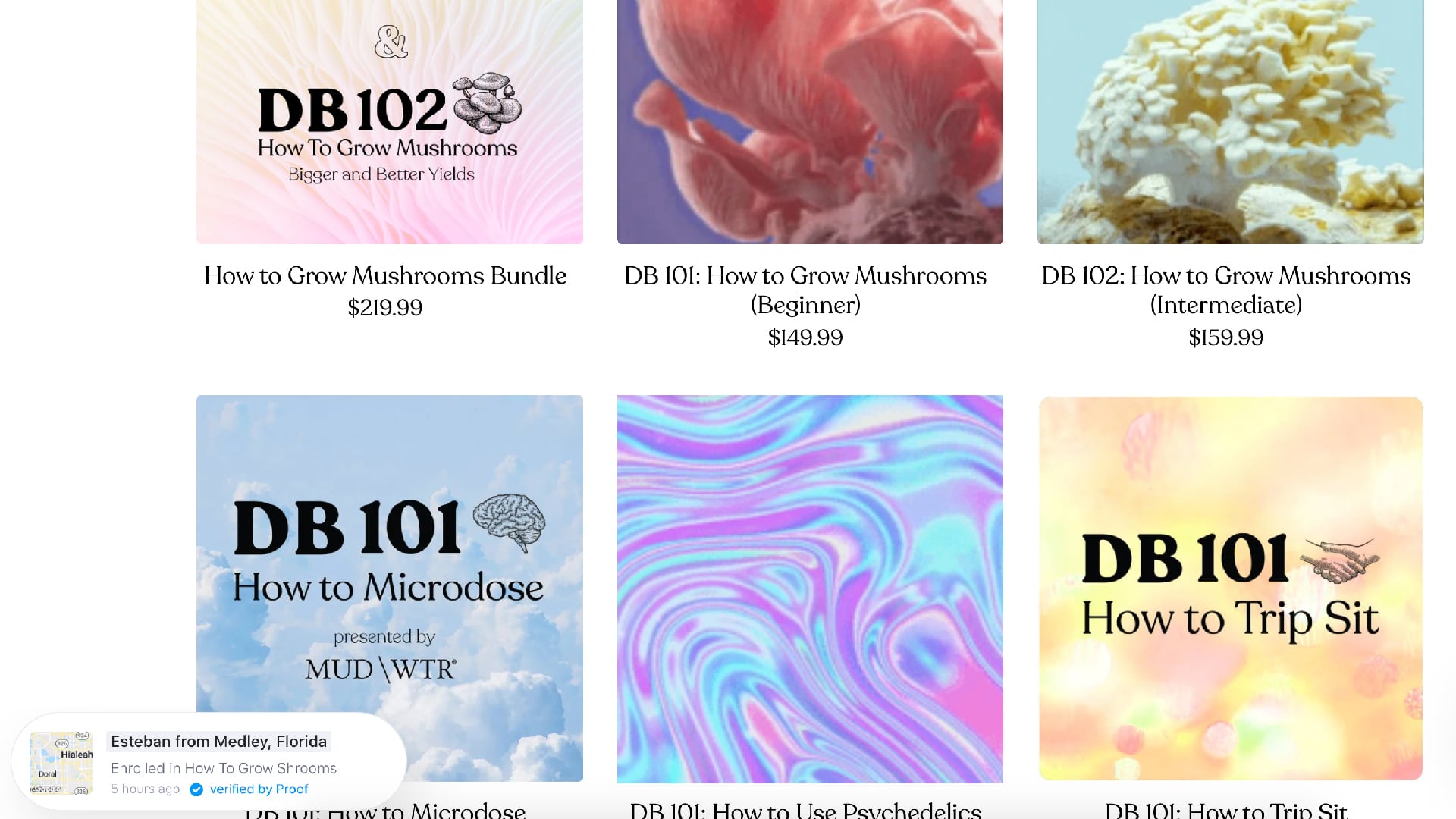

Aside from DoubleBlind’s microdosing courses, its offerings include topics such as “How to Grow Mushrooms” ($149.99 for the beginner course and $159.99 for the intermediate course), “How to Trip-Sit” ($119.99), and “How to Use Psychedelics” ($74.99) — all information that has been generally accessible for free online through websites like Erowid, Bluelight, the DMT Nexus, the Shroomery, and even Reddit.

Another downside to DoubleBlind selling information on illegal substances is that — unlike the websites which list this information freely — it requires you to relinquish personal identifying information in exchange. DoubleBlind’s privacy policy clearly states it will hand over your information to other entities “to comply with applicable laws and regulations, to respond to a subpoena, search warrant or other lawful request for information we receive.”

Averaging all of DoubleBlind’s current course prices (excluding course bundles) equates to a figure of around $180, and DoubleBlind claims that over 7,000 people have taken their courses. A little back-of-the-napkin math with those figures and it looks like DoubleBlind could have made hundreds of thousands of dollars from trafficking in otherwise freely accessible information and understudied science.

DoubleBlind markets itself as “provocative” and its founders, Shelby Hartman and Madison Margolin, are often framed as media-savvy veterans of the War on Drugs, writing about “living psychedelically” in venues such as LA Weekly, High Times, and Rolling Stone.

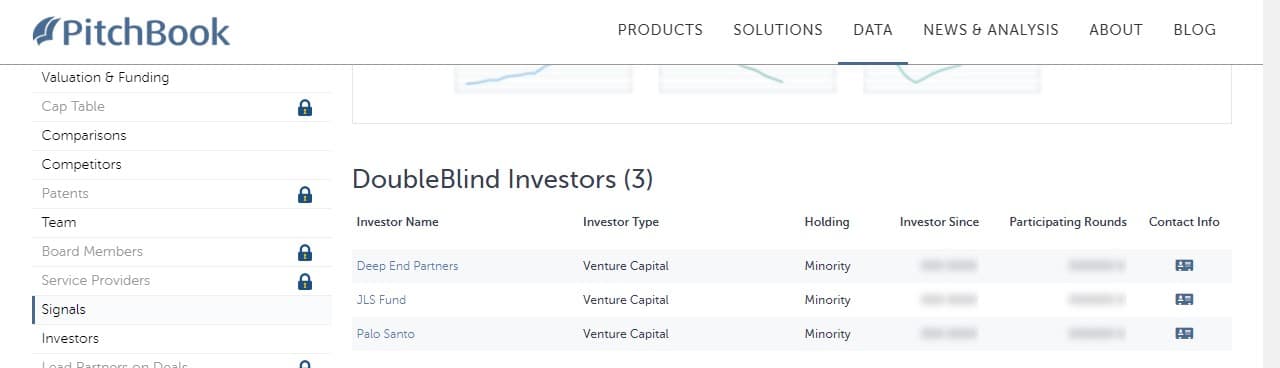

But as the publication ages, it appears to be adopting many similar approaches to the psychedelic pharmaceutical companies it shares investors with — accepting venture capital funding, choosing to ignore science in favor of profits, and monetizing previously-free and open-source community knowledge.

Although DoubleBlind does produce some free content (which often acts as a funnel to its paid classes), its main products pollute the field with paywalled content that seems more committed to capitalizing on the current hype around psychedelics than to scientific rigor.

For more psychedelic marketing missteps from DoubleBlind Magazine, see “DoubleBlind Claims Its Ad Was the ‘First-Ever’ U.S. Psychedelic Destigmatization Campaign — It Wasn’t”

Field Trip creates an “educational” social media campaign, stereotypes and appropriates Indigenous cultures

Field Trip, a for-profit venture currently offering ketamine infusions with plans to expand into classical psychedelics, released a mobile application in September of 2020 called “Trip.”

Through the social media accounts created for the app, Field Trip launched an “educational” campaign that incorporated elements of corporate redwashing — the use of Indigenous American depictions for public relations gains.

The campaign billed itself as “shedding light on time-tested wisdom of native cultures and lands that have brought psychedelic plant medicine work and practices to the world.” However, the exaggerated imagery and stereotyped summaries of Indigenous cultures ultimately resulted in a tone-deaf ad campaign attempting to direct viewers to Field Trip’s app platform.

Hi @RonanDLevy @tripapp @fieldtriphealth,

We need to talk.

-Psymposia pic.twitter.com/cyP5wwsE1S

— Psymposia (@psymposia) October 6, 2021

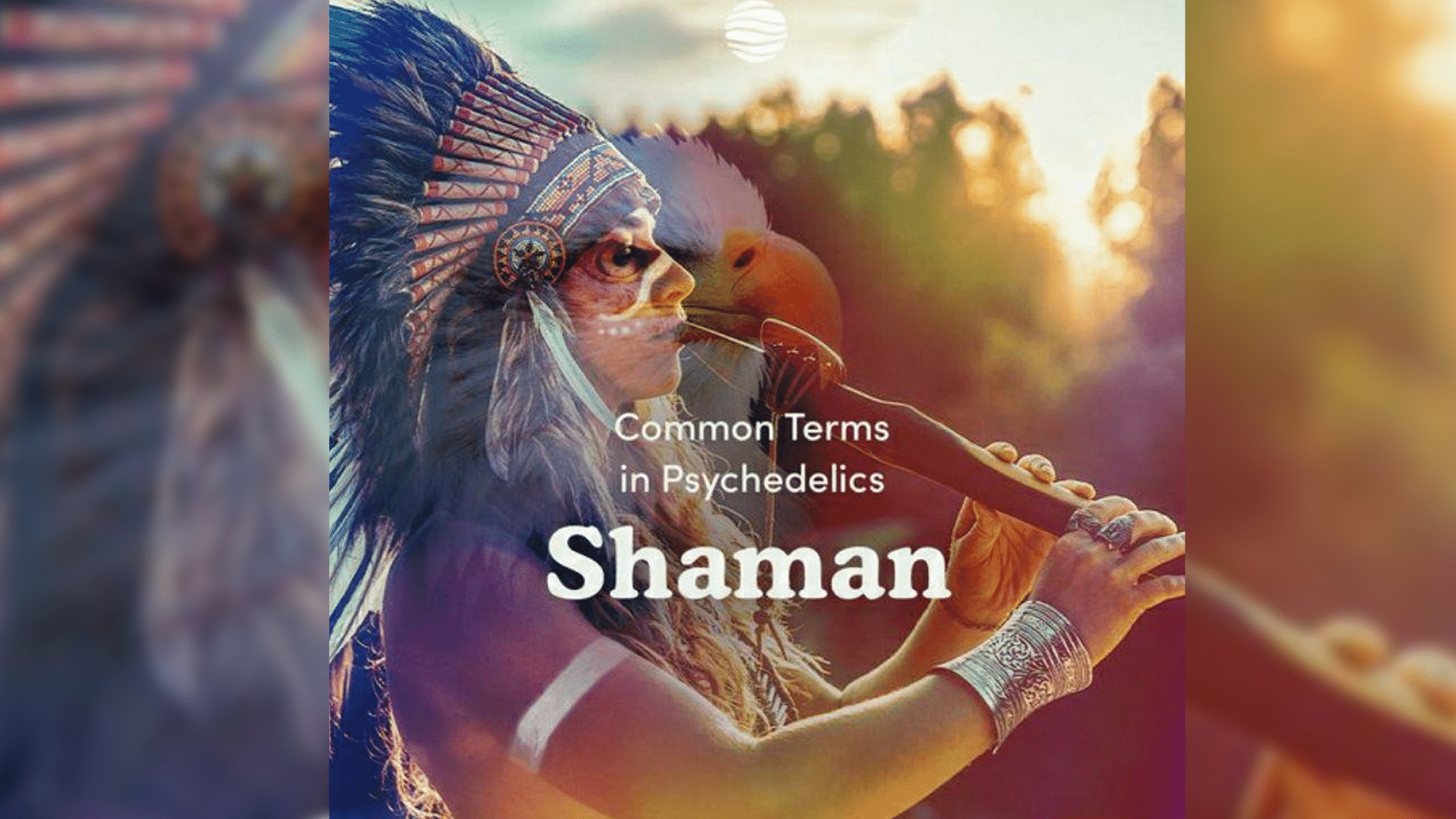

One tweet, defining the word “Shaman,” read: “Indigenous cultures regard shamans as the seers 👁️, the healers 🏹, the prophets 💡. They are believed to have an open connection to the spirit world, which allows them to “see beyond the veil,” or beyond reality as most know it. Head to @tripapp on instagram to read more.”

This was accompanied by an image of a model in a headdress playing a flute. Not only was this photo depicting an individual in plains tribe clothing (a group not historically associated with classical psychedelic use) but a reverse image search revealed that it was a stock photo taken by a Slovakian photographer titled, “beautiful shamanic girl playing on shaman flute in the nature.”

If viewers were to take the bait and visit Trip app’s Instagram page, they’d find a post which concludes, “We remember the OGs that paved this path for us, and invite indigenous voices forth to hear guidance that stems from generations of learning.”

This statement was paired with images offering brief descriptions of a few (so-called by Field Trip) Indigenous cultures: Shipibo, Mazatec, Huichol (who actually call themselves “Wixárika” and were called “Huichol” by Spanish colonists), and Bwiti (which is a syncretic spiritual practice created in the 20th century, not an Indigenous group).

This is a hot ass mess, but can we talk about how terms like "shaman" "seers" don't come from Indigenous cultures in the Americas? This whole series homogenized Indigenous cultures. https://t.co/6kUCZQlZCN

— Gullah Jack (@if3tay0) October 6, 2021

Trip’s Indigenous tokenization is compounded by the fact that leadership at Field Trip has, in the past, made statements dismissing concepts like “sacred reciprocity,” or the idea that companies should give back to the “OGs that paved this path.”

At the 2020 Green Market Summit on the Economics of Psychedelic Investing, Field Trip co-founder Ronan Levy said that the company had no plans for implementing “sacred reciprocity” into its business model.

“From our perspective, we are focused on healthcare outcomes,” Levy said. “Our immediate focus, now and when we give back, is to make sure that we are creating pools of money and capital, but make sure that we can make these treatments — which are not inexpensive — available to more people. The marginalized people who might be excluded from accessing this care, because it is going to be expensive. It is very high touch point. So, I don’t have a great answer in terms of addressing the sacred reciprocity, but our focus, in terms of our commitment, is on patient outcomes and making sure people get access to clinical care.”

The offensive copy and generic stock imagery of this “educational” campaign, paired with past comments from Field Trip’s leadership, diminishes any authenticity it may have hoped to claim. Instead, it reads as the hollow attempt of a pharmaceutical company to pander to marginalized communities and promote a new app without doing anything substantive for the communities to which it’s pandering.

For more psychedelic marketing missteps from Field Trip, see “Field Trip Announces ‘World’s First’ Virtual Psychedelic Therapy, But Forgets To Mention They Aren’t The First And No Psychedelics Are Involved”

Awakn Co-Founder Ben Sessa admits a graph is misleading and made for hype, later spins possible patent legal action into company PR

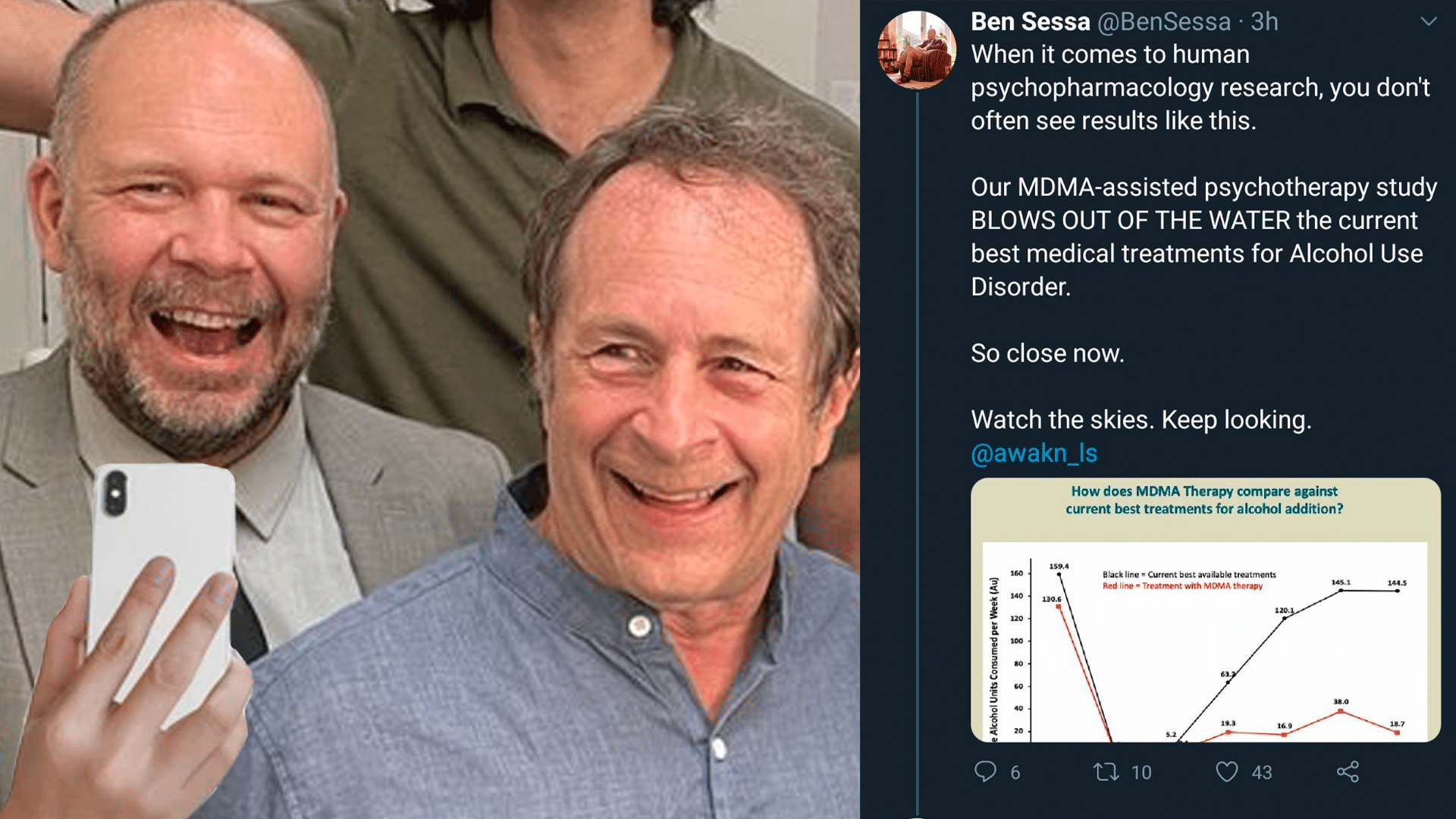

In December of 2020, Ben Sessa, Co-founder and Chief Medical Officer of UK-based Awakn Life Sciences Corp, shared a graph on Twitter he made comparing two different studies on the same graph.

I can't stop thinking about the potential for harms resulting from overeager (& self-interested) researchers hyping psychedelic therapies & instilling unrealistic expectations in potential patients.

The (rare) cases of study participant suicide underscore these concerns. pic.twitter.com/f4PkzRqtOF

— David Nickles (@D__Nickles) December 10, 2020

“When it comes to human psychopharmacology research, you don’t often see results like this,” Sessa tweeted, referencing a graph he created which compared MDMA treatment to abstinence treatment for alcohol addiction. The graph seemed to depict what Sessa wrote next: “Our MDMA-assisted psychotherapy study BLOWS OUT OF THE WATER the current best medical treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder.”

But when questioned about these seemingly-exciting results, Sessa backpedaled.

“Its a bit hyped, fosho, in that these are two separate studies superimposed on one graph,” Sessa wrote. He then responded to another question about the graph: “Its not possible to compare the two groups statistically as this is a superimposed pic of two non-randomized studies to illustrate MDMA vs Treatment as Usual. But it looks good on Twitter…” (emphasis added).

Like I could use HbA1c to measure how exercise effects people w/ pre-diabetes & how metformin works for people w/Type2 diabetes if I put those things on graph together then Metformin will look hugely different. studies don’t have the same populations, goals or designs….

— Emma Tumilty, PhD (@EmTumilty) December 2, 2021

Apparently Awakn thought this graph could be put to use outside of Twitter. The company currently displays the results of a small, 14-person Phase IIa study of MDMA for Alcohol Use Disorder (data collected by researchers at Imperial College London, including Sessa and David Nutt, and acquired by Awakn) on its official website, using the graph that Sessa tweeted as an illustration. The comparison study was also a small, 12-person “observational, questionnaire based, follow-up study [also conducted by Ben Sessa, David Nutt, et al.] in patients undergoing a community alcohol detoxification at Bristol Drug and Alcohol services.”

Notable differences between the two studies include that the Phase IIa study for MDMA included patients being dosed up to two times with MDMA and receiving 10 psychotherapy sessions, whereas it is unclear what kind of therapeutic care participants in the observational, questionnaire-based study received. Also notable: only half (or six) participants in the observational study provided “full datasets at the 9-month follow-up point.” As Sessa noted, “Its not possible to compare the two groups statistically.”

While the study results of the Phase IIa MDMA study were generally positive, with about three-quarters of the 14 subjects (so maybe 10 people) showing some improvement nine months after treatment, the graph is misleading and presumably does not represent data that any legitimate medical professional or scientist would point to as proof that MDMA is more effective than current treatments for Alcohol Use Disorder.

When presented with Sessa’s comments regarding this graph, a spokesperson from Awakn told Psymposia, “the graph you have pointed out was published in the journal of psychopharmacology [sic], and both we and the journal thought it was clear they were from different studies; however, it seems that is not the case from your email. Therefore, we have updated this on our website to ensure the clarity is there.”

Awakn’s Chief Research Officer, David Nutt, was the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Psychopharmacology for over two decades, including at the time the MDMA for alcoholism paper was published, and he remains listed as an “editor emeritus.” Nutt was also a co-author on that paper during his tenure as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Psychopharmacology (a practice which some academics consider questionable).

“I’d like psychedelics to work out — the idea that there might be something really effective for intractable depression or PTSD is amazing. The seeming inability of those pursuing this to do any well-designed RCTs [randomized controlled trials] and talk about them accurately is hampering progress,” said bioethicist Emma Tumilty, regarding Sessa’s graph.

I’d like psychedelics to work out – the idea that they’re might be something really effective for intractable depression or PTSD is amazing. The seeming inability of those pursuing this to do any well-designed RCTs and talk about them accurately is hampering progress IMHO

— Emma Tumilty, PhD (@EmTumilty) December 2, 2021

Tumilty added: “The pattern of talking about results in misleading and overhyped ways, pooling heterogenous data, selective reporting of results, or comparing apples and oranges gives the impression that results are weak or poor and need manipulation to be impressive or persuasive. Robust design and analysis with clear, transparent, and honest reporting is what is needed in this space urgently.”

In another example of how information can be spun and presented for hype, Sessa has taken to describing Awakn as “world leaders” in “MDMA-alcoholism” (based on a 14-person study) and boasting about a seemingly-friendly “Memorandum of Understanding” the company signed with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) to license MAPS’ preclinical data.

Another huge announcement from @awakn_ls

MAPS are world leaders in MDMA-PTSD, & Awakn are world leaders in MDMA-alcoholism.

I've been buddies with Rick & MAPS for >15 years.

Its fab to now be cementing this with a formal collaboration. MDMA is a wonderful medicine.

Onwards😃 https://t.co/EarNDTl6KS pic.twitter.com/gMoAHpTYB0— Dr Ben Sessa MBBS (MD) BSc MRCPsych (@BenSessa) January 19, 2022

While a number of questions and concerns about MAPS have recently come to light, organizational partnerships with MAPS (essentially the most well-established psychedelic organization) have tended to make headlines and inspire investor confidence.

What goes unsaid is that, according to MAPS Executive Director Rick Doblin, Awakn had tried to undercut MAPS and this “Memorandum of Understanding” was only developed after MAPS threatened legal action.

Our CEO @AnthonyTennyson reflects on Awakn's MOU with @MAPS to explore a partnership to utilize #MDMA-assisted therapy to treat #AlcoholUseDisorder (AUD) in Europe. For more information visit: https://t.co/yN8vkCrMkp $AWKN $AWKNF pic.twitter.com/eiTK9GFcOs

— Awakn™ Life Sciences (@awakn_ls) January 19, 2022

In a March 2021 meeting with the Boston Psychedelics Research Group, Doblin explained how MAPS “had a situation with David Nutt [Awakn’s Chief Research Officer]…and Ben Sessa who just did this MDMA for Alcohol Use Disorder study.”

“We got them the MDMA, we trained them, we worked with them on the protocol, we let them cross-reference all of our data, and then we find out that they are trying to patent MDMA for Alcohol Use Disorder,” Doblin said. “They have their for-profit, Awakn, and they thought the only way they could get investment money was if they patented MDMA for Alcohol Use Disorder. So I told Ben that we’re going to challenge their patent. And not only that, they have absolutely no right to do that.”

Doblin went on to cite early writing on MDMA from 1986 which had already identified MDMA’s usefulness for alcohol use reduction.

“So, for all these years later — 35 years later — for them to say they’re going to try to patent MDMA for Alcohol Use Disorder like it’s a new, original invention…it’s ridiculous,” Doblin said.

In the span of a few months, Awakn seemingly walked back their plans to patent MDMA for Alcohol Use Disorder (although the company has filed patents for “MDMA-derived new chemical entities”) and spun the narrative from one of undercutting the organization that supported them, to a positive story about a “Memorandum of Understanding” that was featured in the headlines of a number of investing news websites.

When asked about Doblin’s comments, a spokesperson from Awakn told Psymposia, “we are not aware of any comments from MAPS in regard to this.”

Mind Medicine Australia erases criticism of “Shroom Boom” music video, demonstrates concerning pattern of engagement with criticism

On February 19, Mind Medicine Australia (MMA) — a nonprofit organization attempting to introduce medicalized psychedelic treatments in Australia — released a music video for the song, “Shroom Boom,” written and performed by MMA Executive Director Tania de Jong. The video was released to MMA’s YouTube channel, as well as the YouTube channel “mtaose” which hosts a number of other performances of de Jong and her band, Pot-Pourri.

Posted without comment.

Full video here: https://t.co/bd5Y7kQUS0 pic.twitter.com/27HDVtq25B

— David Nickles (@D__Nickles) February 20, 2022

The song has been criticized by many psychedelic advocates for depicting psilocybin mushrooms as a miracle cure, demonizing other antidepressant drugs, and being generally cringe-worthy (one Twitter user likened it to a mix between Teletubbies, Hillsong church songs, and budget pharma ads).

The song begins with the lyrics:

Why can’t I get out of bed?

It’s not because I am dead

And yet the pain never stops

Antidepressants and side effects

So I tried magic mushrooms

And now I’m feeling so great

Now I’m changing my brain waves

And I’m changing my state

This oversimplification of psychedelic treatment comes at a time when many worry that the current hype around psychedelics may lead depressed people (especially those who have tried other treatments unsuccessfully) to approach psychedelics with unrealistic expectations or as a desperate final attempt at healing.

Dr. Rosalind Watts, the former Clinical Lead at Imperial College’s Centre for Psychedelic Research, commented on this video that the song made her sad and was “irresponsible.”

“Taking magic mushrooms to treat depression is a high risk therapy that requires ongoing support from trained professionals. Psychedelic trips can uncover trauma and very painful emotions. They often require many therapy sessions just to process some of the raw stuff that comes up. They do not magically reset the depressed brain, or heal the world, or the soul,” Watts wrote, responding to the above lyrics as well as the later song lyrics: “Shroom boom, come into the mushroom, healing our planet, healing our souls.”

She continued her comment, stating that psilocybin mushrooms can be very helpful for some people, but that they can also be unpredictable.

“If you are taking antidepressants, please do not stop taking them and eat loads of magic mushrooms. Please do not consider this song to be a health message from a responsible organization, it is most certainly not that,” Watts concluded.

Watts’ concerned YouTube comment — along with a number of other comments presenting criticism of the song — has since been removed.

At the same time that critical comments such as Watts’ were being removed from the video, MMA announced a competition asking people to leave them comments about the video, and like and share the organization’s Twitter post about the video for the chance to win $99-worth of MMA merchandise.

This is not the first time that MMA has received criticism from psychedelic advocates. In November of 2021, a letter was sent to advisors and board members of MMA from “concerned members of the psychedelic community” who claimed to be ex-MMA staff and volunteers. The letter accused de Jong of “bullying, abusive control, and cruel treatment of those she is responsible for, is representing, or has power over.”

De Jong’s husband and co-founder of MMA, Peter Hunt, responded to the anonymous letter by asserting that de Jong is an “incredibly talented and caring human being,” characterizing the letter writers as a “small group” of hypocrites, and painting their concerns as “unnecessary challenges that we constantly have from a small group of spiteful, selfish and rather sad people.” He continued by stating that he worried letters voicing harms regarding psychedelic organizations may send a message to regulators that “we are a community divided by pettiness and that we are incapable of coherent and professional discussion of differences.”

Hunt asked anyone who knew the letter writers to “insist that they behave decently and in a caring and respectful way. Ask them to consider the importance of the work that we [MMA] are doing and to consider the implications before posting small-minded and defamatory material. Please ask them to behave as professionals and bring concerns into the clear and open air where we can assess differences and hopefully come to some form of understanding.”

The writers of the letter state that their choice to remain anonymous was out of fear of litigation from MMA. This fear is not unfounded, as MMA has responded to other online criticism by calling it harassment, calling the police, and — in one case — attempting to get an anonymous Twitter user identified. Psymposia has been informed, by a source who would prefer to remain anonymous, that MMA leadership has also attempted to get an internet forum owner to identify users of their forum who criticized MMA.

Psymposia has also been on the receiving end of defensive responses to criticism of MMA.

During an investigation into MMA’s Certification in Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy program, Psymposia reached out to de Jong, Hunt, and a number of MMA advisors with concerns about accreditation claims and faculty listed on MMA’s website.

Psymposia Managing Editor, David Nickles, laid out these concerns in episode 8 of the podcast Cover Story: Power Trip.

In the episode, Nickles notes that it is “worth pointing out that they [MMA] list Francoise Bourzat [who has been accused — along with her husband — of harming multiple clients] as the first trainer on their psychedelic certificate page.”

This was the first concern that Psymposia reached out about. The second issue was regarding MMA’s representations of professional organizations accrediting its therapist training program.

“On their website, at the time, they had the logos of several Australian professional organizations under the headline ‘Accreditations.’ The Australian Association for Social Workers, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, the Australian Psychological Society,” Nickles said. “And so I reached out to all of these organizations and it turned out that not a single one of them had accredited MMA’s certificate. When I reached out, they said things along the lines of: ‘We don’t know what you’re talking about. Whose website are we listed on?’ In other cases, they had explicitly told MMA ‘no,’ or they actually weren’t accrediting any outside training programs. And once those organizations were made aware of the listings, they asked MMA to remove their logos, which they did.”

In response to Psymposia’s inquiries of MMA and its advisors, someone using de Jong’s email account sent an email to MMA’s board and advisors calling Psymposia a “tiny fringe publication” and characterizing our inquiries as “defamatory statements.”

“These statements [about accreditation and faculty] are incorrect [editors’ note: they were correct] and are a result of prejudice and malicious intent,” wrote someone from an email account that matches one de Jong has listed publicly as her own. The email continued: “These are underground psychedelics people who resent the psychedelic renaissance and the need for these treatments to be conducted in medically controlled clinical environments to treat a range of serious mental illnesses. They are also anti-capitalist and post a lot of vitriol about many leading organizations (NFPs and commercial) in the space.”

This same language had appeared in a prior email to an accrediting organization, which was anonymously leaked to Psymposia. When Psymposia inquired about this email, de Jong denied sending it, telling Nickles, “I don’t know. Like, that is very strange,” even though it was sent from her personal email and signed “Tania de Jong.”

De Jong and Hunt’s rebuttal-of-choice to criticism appears to be to attack the character of their critics; emphasize that their critics are “small,” “tiny,” or “fringe”; and, when possible, erase the criticism altogether, as they did with a number of critical YouTube comments.

As MMA continues to assert itself as the leading organization attempting to bring psychedelic treatments to Australia, its lack of engagement with (and often outright dismissal of) criticism is concerning.

Any entity attempting to claim that level of authority might be expected to have patients’ best interest in mind and be cautious about promoting overblown claims and dangerous practitioners — especially when MMA boasts an advisory panel and “Ambassador” list of over 75 individuals working in psychedelic research fields.

These individuals include, but are not limited to, Rick Doblin (Executive Director of MAPS), Roland Griffiths (Johns Hopkins University), David Nutt (Imperial College London), Ben Sessa (AWAKN Clinics), Bill Richards (Johns Hopkins University), Robin Carhartt-Harris (University of California San Francisco, formerly Imperial College London), James Fadiman (author of “The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide”), Wade Davis (anthropologist and author of “One River”), Albert Garcia-Romeu (Johns Hopkins University), Ingmar Gorman (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies and Fluence), Matthew Johnson (Johns Hopkins University), Gabor Maté (renowned writer on addiction), David Caldicott (Cavalry Hospital), Dan Engle (writer of “A Dose of Hope: A Story of MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy”), Lynn Marie Morski (host of the “Plant Medicine Podcast”), Rachel Yehuda (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai), Johann Hari (author of “Chasing the Scream: the First and Last Days of the War on Drugs”), David Nichols (Purdue), Reid Robison (Chief Medical Officer at Novamind), and Ronald D. Siegel (Harvard Medical School).

[Update 5/25/2022: Since the publication of this article, Lynn Marie Morski and Rachel Yehuda have been removed from the MMA Advisory Panel. Update 7/21/2022: Johann Hari has been removed from the MMA Advisory Panel.]

What does it mean when some of the world’s most respected researchers of psychedelic drugs make common cause with those broadcasting irresponsible or overblown claims to the public? As we have seen, some will speak out against inaccuracies and blatant lies, but others seem more than happy to stick around and lend organizations like MMA their credibility.

Psymposia has contacted MMA’s advisors with concerns about the organization and the information it promotes (well before “Shroom Boom” dropped). At least one advisor requested removal from MMA’s website but remains listed as an advisor. Beckley Foundation Executive Director Amanda Feilding, for example, made a statement in January of 2021 distancing herself from her advisory position at MMA, but still remains listed on the “Advisory Panel” section of the organization’s website. The vast majority of advisors, however, have chosen to remain affiliated with MMA despite the concerns shared with them — some going as far as dismissing Psymposia’s inquiries about accreditation and abusive faculty as “‘tabloid-like’ allegations.”

We are associated with Mind Medicine Australia in their capacity as advocates of psychedelic therapy.

As a scientific research organisation, we do not agree with Tania's views on this particular issue, as they appear to be contrary to the current scientific evidence. pic.twitter.com/1miOdcTCX7

— Beckley Foundation | Psychedelic Research (@BeckleyResearch) January 8, 2021

The Comedown

All of the organizations in this article share a concerning desire to hold the hands and shape the minds of the next generation of psychedelic users.

DoubleBlind’s “About” page reads, “We’re not speaking to the veteran tripper nor evangelizing to the anti-drug square. We are speaking to everyone who is curious about psychedelics.” And if one were to read that sentence on DoubleBlind’s website, they’d likely be interrupted before the end by a pop-up ad for how to avoid “Newbie” psychedelic mistakes.

Organizations like Field Trip, Awakn, and MMA — those looking to medicalize psychedelics — often identify their ideal customers as those who appreciate going to their doctors and might be too nervous to try psychedelics on their own.

Both media-based and clinic-based businesses have identified an influx of interest in psychedelic drugs from an increasingly mainstream crowd. Whether these new folks are struggling with untreatable PTSD or just happen to live in a state where psychedelic drugs are newly decriminalized, many businesses have deemed the most effective sales pitch to be marketing miracles; demonizing other forms of treatment; fronting as cultural experts; or overstating research.

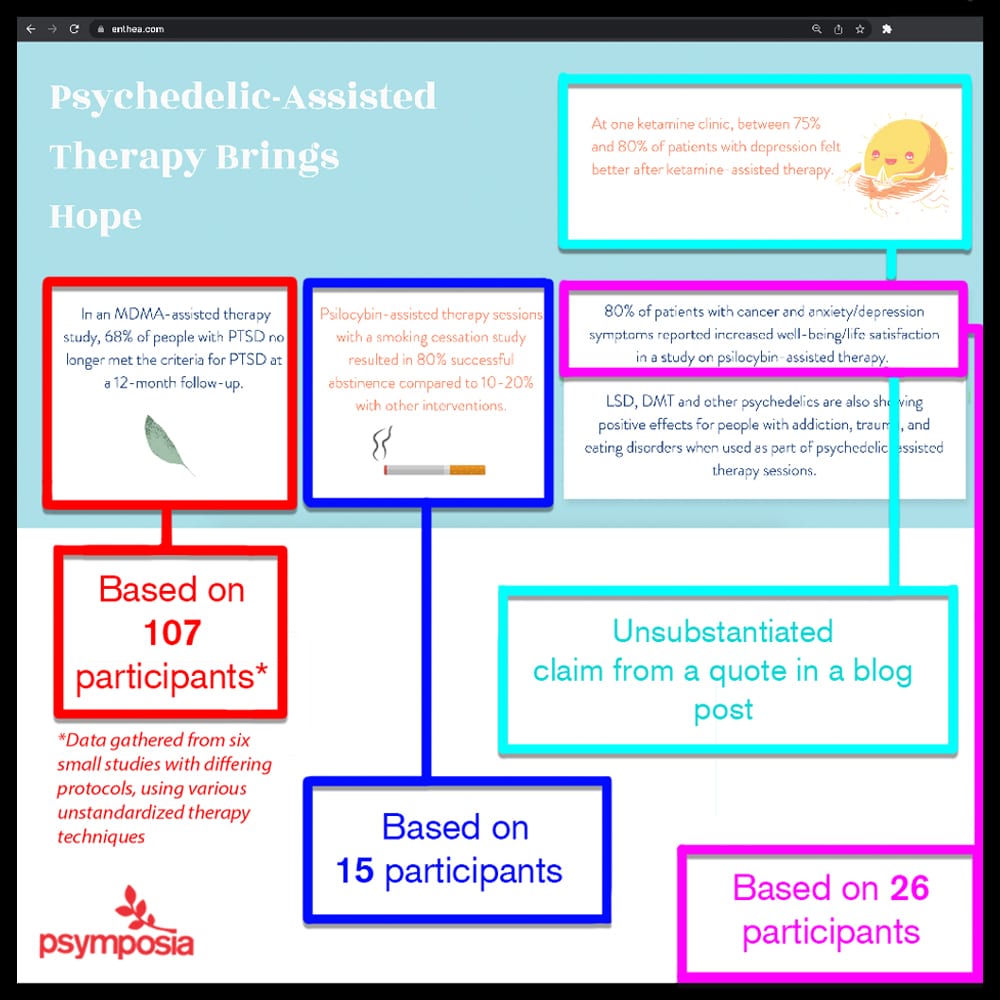

To date, much of the data being trumpeted in online advertising has been garnered from small-scale studies. For example, Enthea — a non-profit benefit plan administrator promoting psychedelic healthcare and partnering with companies like Dr. Bronner’s — references a 15-person smoking cessation study on its website to claim that psilocybin-assisted therapy has resulted “in 80% successful abstinence compared to 10-20% with other interventions.”

Even in the paper where Enthea found these numbers, the authors note: “Additional, carefully controlled research in larger, more diverse samples is necessary to determine efficacy.” And yet, these study results (excluding numbers of participants) are already being used as promotional material for, in this case, a company that wants to sell you and your employer access to networks of psychedelic providers.

It seems that too few of these companies and media outlets are interested in moving slowly and mitigating unrealistic expectations, potential dangers, and oversights around psychedelics. And while plenty of entities participating in the newly-mainstreamed psychedelic industry may state that patient safety and risk management are important to them, they still seem willing to stretch the science and complicated cultural histories of these substances in search of a profit. In doing so, these organizations disregard the well-being of the very customers they are so eagerly pursuing.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Russell Hausfeld

Russell Hausfeld is an investigative journalist and illustrator living in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism and Religious Studies from the University of Cincinnati. His work with Psymposia has been cited in Vice, The Nation, Frontiers in Psychology, New York Magazine’s “Cover Story: Power Trip” podcast, the Daily Beast, the Outlaw Report, Harm Reduction Journal, and more.