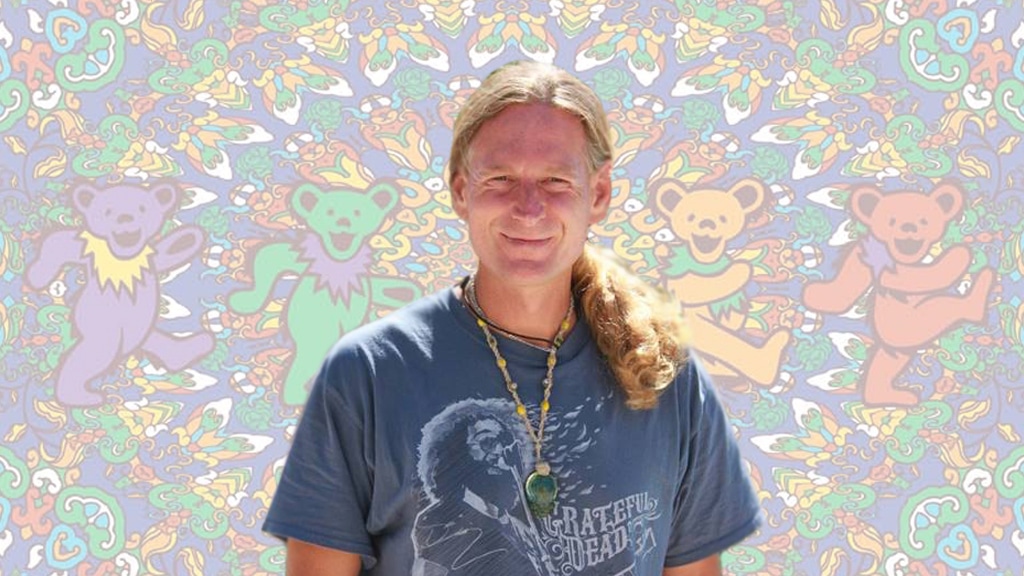

Just over two years ago, Timothy L. Tyler was granted the chance of a lifetime when President Barack Obama commuted his double-life prison sentence. Tyler was arrested in 1992 and convicted in 1994 for selling LSD and cannabis to a police informant.

Despite Obama’s action in August 2016, Tyler was not released from federal prison for another two years, until May 29, 2018. Even after leaving prison, he did not regain full freedom. He spent time in Las Vegas, Nevada first in a halfway house and then on home confinement.

Exactly two years later on Thursday, August 30, 2018, Tyler was released from home confinement. Twenty-six years after his arrest in 1992, he is a free man.

In an exclusive Psymposia interview, Tyler recounted the day that he first received the news. He was ordered to go to an office at 2:00PM, which was unusual. As he was ushered into the office, the guard let him through the door without asking him why he was there—also unusual.

In the waiting room Tyler met two other inmates. No one knew why they were there, but they learned they had each made a clemency petition: could this be the moment they had waited for all these years?

The first man was called into a separate room to receive a telephone call. When he left shortly after, he simply flashed the other two men a thumbs up.

Finally, Tyler took his call. It was from Professor J.P. “Sandy” Ogilvy, a law professor at the Columbus School of Law at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. Ogilvy had handled his clemency petition.

“Timothy, I’ve got some good news for you,” Ogilvy said. “The U.S. Pardon Attorney decided to give your clemency petition to The President of the United States and he signed it. He gave you a two year release date, with a requirement that you enroll in a residential drug abuse program (RDAP). You no longer have a life sentence.”

“I was trying to hold everything back to not break down and cry,” Tyler said of that moment. “Even the woman who handed me the phone, I almost wanted to hug her—she looked like she was gonna cry.”

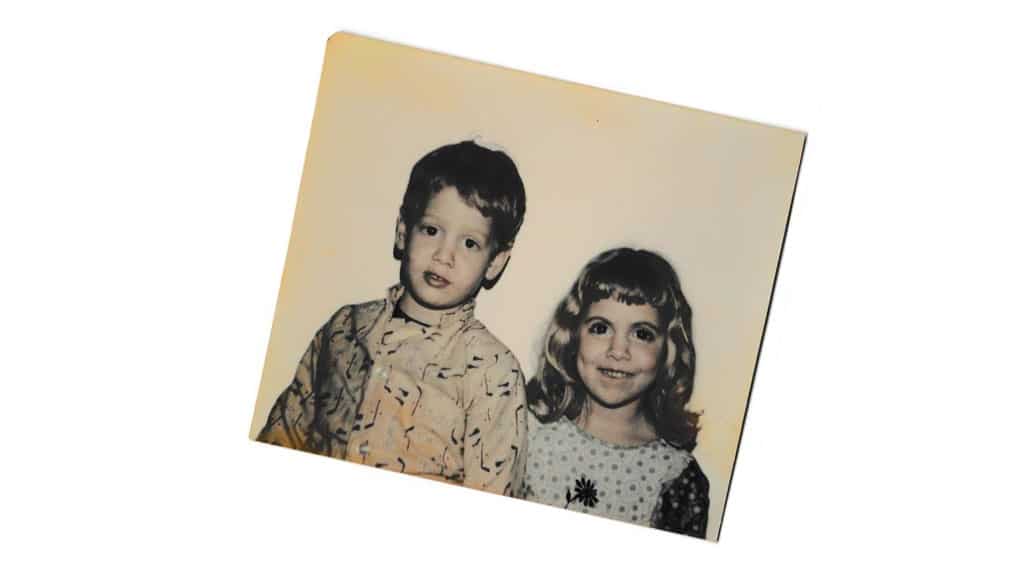

Tyler left the office in a daze. When he returned to his quarters, he called his sister, Carrie, who didn’t answer. He then called his mother, Lura, and gave her the incredible news. She was so shocked she couldn’t understand what he was saying. “I felt like all the negativity she had in her life for the last twenty-six years, all the depression, just lifted out of her, when she realized that I was going to come home.”

Tyler’s gift is one too many prisoners will never know of–among them his late father, Timothy Varnum Tyler, who was also implicated in his son’s drug charges. The junior Tyler refused a plea deal to avoid testifying against his father, but T.V. Tyler received ten years anyway. He died in prison at age 53, with eighteen months remaining on his sentence.

Tyler lived out the remaining two years of his sentence as a new man. “When I got a release date, I finally had a date to look forward to for the first time,” he said. “I now understand how it feels for people that come in knowing they’ll be let out in five years, to know that a day will come when they’ll be let out.”

“The U.S. Pardon Attorney decided to give your clemency petition to The President of the United States and he signed it. You no longer have a life sentence.”

Twenty-Six Years, Eleven Prisons

By 2016, Tyler had served twenty-two years of his life sentence, plus two years spent in county jail before his conviction. Over the years, he was confined in nine different facilities. His long journey began at the United States Penitentiary (USP) in Atlanta, where in only his second week he witnessed a man get stabbed with a knife.

That same year, Tyler’s roommate had a knife planted on him, and both men were unjustly blamed for it. They were punished through a form of torture with which he became too familiar throughout his prison sentence: solitary confinement. In prison, it was simply called ‘the hole’. He was put in ‘the hole’ for thirty-seven days his first time.

Tyler spent seven years at USP Atlanta from 1994 until 2001, when he was wrongly accused of trying to escape the facility. Before being ‘shipped’ to a new facility, he was punished with five months in ‘the hole’. He was then transferred to the USP in Beaumont, Texas, about 100 miles east of Houston.

In the Beaumont facility, where Tyler spent three years, he started making wine and distilled alcohol. “It was a very violent prison,” he said, “and I looked at my surroundings. If you’re an alcohol maker—called the ‘wine and shine guy’—they’re not gonna bother you. You’re looked on highly, everyone needs you.”

This mentality helped Tyler survive two and a half decades in prison. “I just adapted to my environment and made the best I could of each day.”

But while Tyler’s winemaking earned him favor, it increasingly caused drunken brawls among his peers. He blames himself for what he calls his ‘bad karma’. He was repeatedly put in ‘the hole’ for his illicit activities, until he was finally threatened with a six month confinement. His mother and sister offered to send extra money to his commissary account to help him avoid further repercussions. He quit winemaking in 2003.

Tyler was imprisoned in USP Beaumont until 2004, then was moved to the USP in Victorville, California, where he was kept for a year and a half. Prison unrest resulted in a transfer in 2006 to the USP Pollock in Louisiana. He was kept there for three months before he was the victim of an assault.

Tyler was then moved to the USP Lee in Virginia for two years, where he suffered manic episodes. As a result he was moved to the United States Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri. “If you go long enough without attention or affection, you lose your mind,” he said. He declined to shed further light on those dark moments.

Tyler’s mental state recovered quickly. But without being interviewed or diagnosed, he was forced by prison staff to take a medication (Risperdal) under threat of being permanently locked in solitary. He eventually agreed to take it for thirty days, then convinced the doctors to switch him to lithium. They promised if he took the treatment they would allow him to leave the facility.

After taking lithium for twelve months Tyler gained significant weight. The doctors, true to their word, sent him to the USP Allenwood in Pennsylvania. He ceased lithium treatment and suffered withdrawal symptoms, but ever since has been healthy.

While at the Springfield facility, the doctors also noted Tyler’s blood pressure was slightly abnormal and coerced him into taking Zocor briefly. Upon his release, he was horrified to learn that the makers of both Risperdal and Zocor received class-action lawsuits against them for side effects associated with their treatments.

Throughout his life, Tyler has avoided taking any medications. He has always preferred herbal or naturopathic treatments, but these were not available behind bars. For ten years, he yearned for a simple olive oil and epsom salt detox treatment.

“I’ve got all that stuff now I’m out. The good health I have right now is amazing, I knew I could feel like this but I couldn’t while in prison. Which is sad, because you’re only supposed to be in prison to be kept away from society, not to be slowly dying every day.”

He chuckled. “They tried to kill me, I feel like, but it didn’t work.”

After Springfield, Tyler was kept in USP Allenwood for one year, then was moved intrastate to the USP Canaan for four years and two months. Finally, he was brought to the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) in Jesup, Georgia. His four years there were his last in prison.

“If you go long enough without attention or affection, you lose your mind.”

I Will Get By

At Tyler’s first facility, USP Atlanta, he was allowed to have an electric Fender Stratocaster guitar. He was not allowed to take it with him when he was moved, but some of the other prisons had nylon string guitars in the recreational areas.

Tyler practiced guitar when he could, but often couldn’t hear himself in the loud rec rooms. The situation worsened when, about twenty years ago, he lost all hearing in his left ear. Some of the prisons had band practice rooms, though they had long waiting lists of up to two years. He performed in a talent show while in FCI Jesup.

Tyler’s access to recorded music behind bars was very limited. He was allowed to buy a radio and tune into local terrestrial stations. But for a devoted Deadhead, FM classic rock stations are a poor substitute for the vast canon of underground, bootleg tape recordings the band’s fanbase has created over the decades. “On the radio, you might hear one GD song – ‘Touch of Grey’ might come on every so often – but I wanted to listen to all their songs, and I wasn’t able to do that.”

To supplement, Tyler played Dead songs on his guitar, and let his sister play their music over the phone for him. In 2012, he was allowed to buy an MP3 player. He filled it with Grateful Dead tunes, which he could buy for $1.55 each from the prison computer system.

“Even then, I only listened to it for a half hour a day,” he said. “I knew they could always take it away from me. I learned to not enjoy things to their full capacity.”

Life After Commutation

Life after commutation was not easy for Tyler. He described his time in the mandatory residential drug abuse program (RDAP) as the hardest eight months of his life. He wasn’t permitted to exercise, and even had limited access to food. “What really set it off was they told me I could never listen to the Grateful Dead again. I told them I wouldn’t stop, and I’ll always consider LSD a sacrament, so they tried to make me retake the classes all over again.”

While in RDAP, Tyler lived with two other men in a low-security, cramped cubicle hardly suitable for even two men. The RDAP staff were surprised that he never complained. “They told me I adapt to my environments too fast. They were afraid for me. But of course I had to learn to adapt, over twenty-six years in prison.”

Tyler never completed the RDAP, even though he helped nine other inmates do so. He was grateful, however, to learn public speaking skills through the program. But after quitting RDAP, he attracted the ire of the program doctor, who campaigned to have him punished. He was put in ‘the hole’ for three months and three days.

Deprived of exercise and a vegan diet, Tyler almost starved. A sympathetic orderly who snuck vegetable scraps under the door helped save his life. “There were days in there I thought I wouldn’t make it out alive,” he admitted. “I even used coffee enemas each day to try to survive.”

“When they let me out of the hole,” Tyler explained, “I found guys in the kitchen who every day brought me tofu, oatmeal, and bags of apples—I ate five apples a day. I started playing handball three and a half hours a day, I got a lot of sun, and I got in real good shape. The last eights months at Jesup were some of the best I had behind bars.”

After overcoming the indignity of this situation, Tyler came up against one last challenge before being released—his own roommate. “This man needed a place to live, but I didn’t wanna get in any kind of trouble. I didn’t like him and he knew it. He tried to get me locked up three days before I left so he could steal all of my property.”

The man—imprisoned for an offense Tyler won’t name—wrote a falsified ‘note’ on him, and he was confronted by prison authorities. He swore he wanted to do nothing to harm the man just before his own release. “So I went back to my room knowing that he tried to get me locked up,” he said, “and for three days I had to live with him.”

“What really set it off was they told me I could never listen to the Grateful Dead again. I told them I wouldn’t stop, and I’ll always consider LSD a sacrament, so they tried to make me retake the classes all over again.”

Freedom At Last

On May 29, 2018, Tyler was released from FCI Jesup. “Even until the day I walked out of prison, I couldn’t believe it. I’m not really going home, am I? As soon as I walked through that gate, I started crying. I couldn’t believe it. I’m actually walking out this door!”

His mother Lura and cousin David came to greet him. Lura then returned home to Florida while Tyler and David took a bus to Savannah, Georgia. They met with Wes Bruer, a journalist currently producing a documentary on him. For the first time in twenty-six years, Timothy Tyler visited a beach. “I broke down as soon as I got to the sand and went into the water.”

The three men then drove to the Atlanta bus station, where they met Malik King, a representative from the CAN-DO Foundation. King and several other Deadheads brought Tyler some gifts: a vegan Jerry Garcia ice cream, a Grateful Dead picture book and poster, and a hundred dollar bill. “I was so happy to see some Grateful Dead family there, it was a blessing. Family still exists and they made me feel welcome. Since then I’ve been feeling really welcomed.”

When Tyler boarded the bus, he noticed a beautiful woman who sat down next to him. She smiled and reached for his hand.

“It’s Like Space Age Out Here!”

The group traveled across the country to Nevada. When at last Tyler arrived in Las Vegas, he was required to live in a halfway house, a supervised living facility for people who are transitioning from prison. While there, he could only travel outside by requesting a pass ten days in advance, and he was required to complete a ‘residential re-entry’ class.

One bizarre experience was when Tyler received a four-hour pass to visit a Wal-Mart. “That was overwhelming. All those people there. Then my sister gave me a credit card with my name on it to use while I was there. I didn’t even know how to use it–everything was all new to me.”

Outside the walls of the store, even mundane objects like billboards amazed Tyler. “They got billboards with pictures that move in them. It’s like space age out here compared to when I left.”

Between fifty to one-hundred people at a time lived in the halfway house. Often, residents’ stints would be cut short if they failed mandatory drug testing. Many residents, for example, would take advantage of legal cannabis dispensaries in the neighborhood—but regardless of state cannabis law, this violated house rules.

In August, however, Tyler transitioned to home confinement. This allowed him to live on house arrest nearby with his sister. He was required to wear an electronic monitoring bracelet on his leg, which connected to the home telephone.

Tyler had similar travel restrictions as when he lived in the halfway house. He was allowed on weekends six hours each day to travel, and three hours, three days during the week to use the gym. One of the more absurd requirements was his need to petition for a pass to visit the swimming pool twelve feet away in his sister’s own backyard.

Since living with his sister, Tyler was required to check in twice a week at the halfway house, to conduct breathalyzer tests and continue with his mandatory classes. He estimates that in the last two months of his house arrest, he was administered twelve drug tests (about once every five days).

“Even until the day I walked out of prison, I couldn’t believe it. I’m not really going home, am I? As soon as I walked through that gate, I started crying. I couldn’t believe it. I’m actually walking out this door!”

Reuniting With The Dead

Armed now with a fresh start in life, Tyler has several ideas for where to go and what to do. Among his goals is a desire to help other people be released from prison. He wants to try to write a book about his experience, or work with organizations like Families Against Mandatory Minimums who helped campaign for his release.

“If I can do good out here and people see me, it’ll give more people that were left behind another chance,” Tyler told me. “I want to help make that happen however I can.” He also wants to do lectures or speaking tours—but not before he gets his teeth fixed. His dental health suffered while behind bars, and he wants to visit a dentist.

Tyler also wants to learn some trades, like T-shirt making, or help with his sister’s herbal sales company. He also wants to once again see the surviving members of the Dead.

When Tyler learned of a Dead & Company concert in Mexico, he tried auctioning one of his late father’s toys on eBay. “As soon as I put it up, I had a bunch of people respond who told me to forget about it and start a GoFundMe,” he said. “Within four days they sent me enough money to go on this trip. Now I’m going to Mexico for two weeks in January to see Dead & Co. I’m also going to visit the Mayan ruins; I’m really lucky.”

Tyler has understandably struggled to adapt to modern technologies since achieving freedom. “I went in over twenty years ago with cassette tapes, and then I come back out and there’s all this advanced stuff I’ve never seen before.”

While in prison, Tyler had access to a basic computer with limited functions. Starting in 2010 he had access to CorrLinks, an email system operated by the federal Bureau of Prisons that allows inmates to communicate with people on the outside.

“I never used a cell phone. I was warned years ago that if we were trying to get a clemency, do not get caught with a cell phone. When I got out, my mother handed me this phone I’m talking to you now on. I said, how do you use it? Where’s the buttons on it? It was pretty weird.”

Tyler slowly learned the functions of his Samsung Galaxy cell phone. He was delighted when he learned how to take pictures, then send them to a CVS pharmacy and pick up the prints. “It’s like Star Trek, or Back to the Future!” he exclaimed.

But even using some bathrooms proved difficult. “I couldn’t figure out how to turn the water on or flush the toilet. I looked everywhere, I looked under the sink, I couldn’t turn it on!”

Tyler was introduced to social media on his cross country bus ride. The attractive woman who sat beside him helped him set up a Facebook account; in one bus ride, he made 600 friends.

Besides digital photography and social media, Tyler is learning how to listen to music in the ‘space age’. Gone are the days of analog cassettes and CD’s. While in prison, he missed the Napster and illegal download era, the debut of the iPod and MP3 players, the rise of iTunes and digital download stores, and finally the transition to digital streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music. He is mostly using YouTube to find his favorite music, where he can search for old Grateful Dead videos and newer footage.

“I went in over twenty years ago with cassette tapes, and then I come back out and there’s all this advanced stuff I’ve never seen before.”

The People We Left Behind

As Tyler reenters a technologically transformed society, he reflects back on the people he left behind in prison. He recounted the story of a friend he made behind bars, first arrested in 1980, that protected him and ‘had [his] back’. But because this man killed someone in a prison fight, he will never leave prison. Tyler made many unlikely friends, including ‘Italian Family guys’. “Because of them I was able to live in prison without doing the stuff some gang members pressure you to do.”

Because of his backstory and his charges, Tyler was treated with more respect and admiration than other inmates who were incarcerated for greater offenses. “Even many staff members, lieutenants—even wardens said, ‘This is ridiculous. They gave you life, what the hell?’” he said. “There were people in there for doing stuff to children that didn’t get as harsh a sentence as I for selling paper me and my friends considered a sacrament. I was almost looked at as being in there for a religious crime.”

Tyler noted the absurdity of drug prohibition in the United States. “Apparently, society does want people to have legal access to weed,” he told me. “President Trump could let all the pot offenders out of prison and legalize weed at the very least. But we need to reevaluate the prison laws in this country. The punishment needs to fit the crime.”

Tyler’s voice grew heated. “Many of my friends have died in prison,” he said. “If you took all of the guys with life sentences now and gave them a release date—no matter how many years it took—you’d dramatically reduce the violence in federal prisons, instantly.”

Timothy Tyler vows to be a role model, and show that people can be reformed without suffering unnecessary punishment. “We’re not hurting anyone by releasing these people,” he told me. “I learned my lesson fifteen years ago—the rest is just wasted time and taxpayer money. You have to forgive. Even me—I have to forgive the people who told on me, and took my father from me. Forgiveness is the key to all doors.”

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.