Turn Off Your Mind, Relax—and Float Right-Wing?

On January 6th, 2021 at least two psychedelic heads stormed the United States Capitol. Strange as it may seem, those adhering to right-wing politics haven’t just established a beachhead in the psychedelic renaissance—they’re maneuvering to own it.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

The term “conspirituality” was coined in 2011 by Charlotte Ward and David Voas to describe the merging of conspiracy and spiritual thinking. This phenomenon isn’t new, but its relevance to the recent violent—if short-lived—seizure of the US Capitol building should be obvious. The motivation for the coup attempt was itself rooted in a conspiracy theory that the presidential election was stolen. Many of the participants were followers of “Q,” an anonymous Moses-like character promising to lead his people out of the elite pedophile-pizza-basement into an awakened promised-land of a morally cleansed America. Psymposia previously reported on one emblematic case of conspirituality at the Capitol: that of Jake Angeli Chansley, the “QAnon Shaman.” In his own words, Angeli made it clear that psychedelics are central to his understanding of the universe. But who would have guessed that not one, but two diehard psychedelic heads would have spearheaded (pun intended) the Capitol invasion?

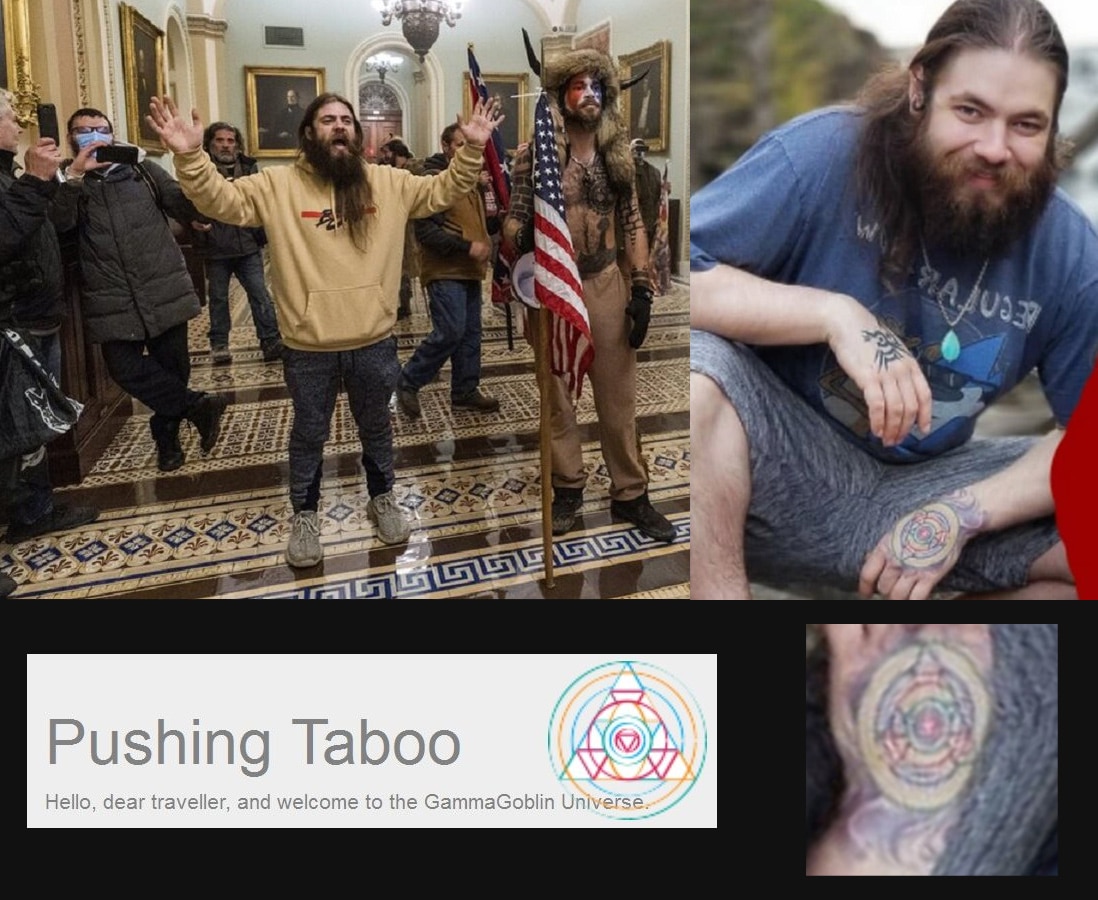

First reported by The Birmingham News, William Watson, 23 (photographed alongside Chansley in an oversized yellow hoodie) was out on $103,000 bond for LSD and cannabis trafficking charges. Watson was arrested last July in possession of a kilo of cannabis and more than 4 grams of LSD (roughly 40,000 doses at 100 micrograms each), according to court records. There was a brief spasm of paranoia on the right that Watson was actually “ANTIFA,” as it was alleged that his left hand tattoo was a stylized sickle and hammer, but Watson himself (and fact-checkers) rebutted the charge—the image was from the video game Dishonored 2.

Yet fact-checkers missed what an astute Psymposia reader did not: Will Watson’s right hand is tattooed with the logo of a well-known psychedelic supplier, GammaGoblin. GammaGoblin is the nom de guerre of perhaps the most prolific darknet LSD distributor. In response to Psymposia’s request for comment, GammaGoblin wrote:

“Well, we have no power over what people put in and on their bodies. My only comment would be: that’s a nice tattoo, kudos to the artist. We always steered clear from political, religious or ideological matters in general. Of course we have our own beliefs but when it comes to our mission, we just believe in a free access to the medicine that we spread, nothing less, nothing more. So I really hope we will not be dragged into a political or extremist narrative on a basis that someone involved had our logo tattooed on his hand : )”

An avid Alex Jones listener, young Watson was allegedly sitting on a virtually inexhaustible supply of LSD (if this is indeed crystal LSD and not draconian courts weighing blotter paper). Jones, a far-right conspiracy commentator, has repeatedly addressed the significance of psychedelics (as more of a recurring, vivid fixation than an endorsement) and when Jones put out the call to rally in DC on January 6th, Watson was among the thousands who answered. It is now apparent that Jones played a significant role in securing funding for the rally.

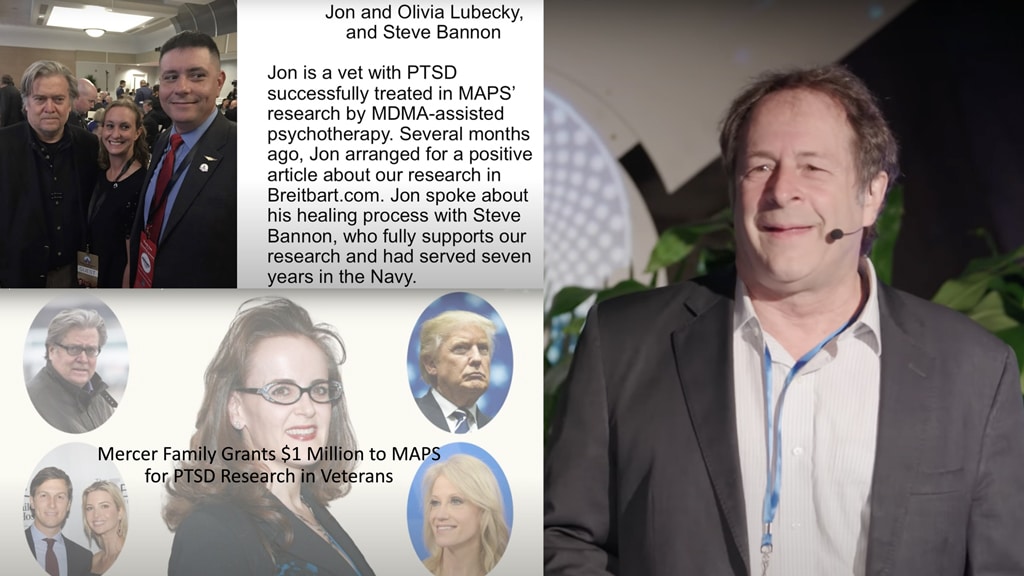

Recent events highlight why it’s a problem that the “psychedelic community” doesn’t like to talk about politics. Some posture as though a personalized, chemically-induced revolution would render earthly disputes null and void. Others pull from the centrist bag of tricks, pretending that discussions of politics other than their own are divisive. Nevertheless, the biggest players in the psychedelic game have no such reservations about their own right-wing, reactionary politics. Billionaire Peter Thiel recently sunk $12 million into ATAI Life Sciences. Beyond his enthusiastic support for Trump, Buzzfeed reported that Thiel hosted a dinner for Kevin DeAnna, an influential white supremacist activist. Christian Angermayer is the founder of ATAI, a fan of Trump, and directly helps prop up at least one dictator. Rebekah Mercer pledged $1 million to MAPS. She has also backed Cambridge Analytica and Breitbart, and is the co-founder of Parler, a far-right response to Twitter where white supremacists, misogynists, anti-LGBTQ bigots, and antisemites take refuge—and which was instrumental in coordinating the storming of the Capitol.

When these are the sort of folks throwing big money at psychedelic research, it’s no wonder that researchers are reticent to venture too deeply into political discourse. Another common anxiety among psychedelic reformers is that if the psychedelic community starts to look too unruly, Uncle Sam will bring the hammer down again. So when Eddie Jacobs penned a piece for Scientific American posing the question What if a Pill could Change your Political or Religious Beliefs?, a reply was inevitable. Jacobs posited that psilocybin may cause people to become more liberal or abandon religious orthodoxy, and that this might complicate bipartisan support for research. Dr. Matthew Johnson, Professor and Associate Center Director at the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research, and Dr. David B. Yaden, a postdoc at Hopkins stepped in to soothe establishment fears. In their Scientific American reply, There’s No Good Evidence that Psychedelics can Change your Politics or Religion, Johnson and Yaden tamped down alarmism that psychedelics might bring about radical change, stating that there is no refereed scientific research that psychedelics are likely to change one’s party affiliation or religious membership.

Prior to this exchange in Scientific American, I argued that psychedelics are unlikely to reduce authoritarianism, because (anecdotally) there are too many dedicated authoritarians who seem to like them just fine. Another study (co-authored by Johnson) noted that a single dose of psilocybin can leave patients scoring higher on a personality trait called openness. Openness is a basic personality trait that describes individual receptivity to new ideas and experiences. And it is worth noting the 2014 Carhartt-Harris (et al.) study titled, LSD enhances suggestibility in healthy volunteers. Taken together, these studies lend weight to the idea that psychedelics can make people gullible.

While the Carhartt-Harris study suffers from the small sample sizes that plague psychedelic research, its results do seem to comport with the body of psychedelic therapy literature, potentially pointing towards its very mechanism of action. Such effects could explain why experiencing chemical suggestibility while hanging out with someone offering (presumably) helpful suggestions for coping with your long-unsolved psychological problems has such value. In his paper Consciousness, Religion, and Gurus: Pitfalls of Psychedelic Medicine, Johnson calls this effect of psychedelics “behavioral plasticity.” Such behavioral plasticity can play a role in radicalization. According to a survey of 75 fascists conducted by Bellingcat entitled, From Memes to Infowars: How 75 Fascist Activists Were “Red-Pilled,” four cited tripping on LSD as key to their embrace of Nazi ideology. Indeed, Johnson devotes the majority of his article to discussing the dangers of clinicians imposing their beliefs on clients:

“The powerful subjective nature of psychedelic experiences can be leveraged toward explicit harm, as in the extreme case of Charles Manson and his followers.”

Johnson’s warnings are important and valid, but they raise the question: should we not also seriously consider the dangerous, antisocial political beliefs and actions of major funders of corporadelic endeavors? If, as Johnson argues, it is inappropriate for clinicians to introduce their worldviews to patients, how can psychedelic communities shield themselves from the open right-wing bent of the psychedelic industry’s biggest investors? I reached out to Dr. Johnson for comment but did not hear back before publication.

A common misunderstanding about the social impact of investment and philanthropy holds that all money is good money as long as it’s going towards good work. First, this assumption ignores the real tax and brand benefits gained by philanthropic funders, who can point to the “good works” they support whenever critics enumerate their dirty deeds. Anand Giridharadas succinctly describes such reputation laundering by pointing out that many of these companies “create harm in billions and do good in millions.” With investment, there is no analogous argument, however poor—stakeholders have considerable power, and they use it to set agendas in pursuit of financial returns. Second, since funders spread cash to many docile pots, they can saturate the discourse with a curated set of ideas which serve those who paid for them. Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman called this “manufacturing consent.” For a synopsis, check out a video animation of the media theory, narrated by Amy Goodman of the nonprofit news outlet Democracy Now!

The will of funders has immense cultural reach, and is used to assert the parameters of conversation. For example, the managing director of Thiel Capital—Dr. Eric Weinstein—coined the term “Intellectual Dark Web” (IDW), a moniker adopted to describe a loosely defined group of culture warriors whose main goal is to counter the gains made by various liberatory projects (e.g. Black Lives Matter, trans liberation, women wearing makeup in the workplace). Several nodes of the IDW have more than succeeded in broadcasting reactionary ideas while flirting with psychedelia to polish their “rebel” cred.

One group that has successfully capitalized on the marriage between psychedelics and right-wing thought is Rebel Wisdom. Their founder, David Fuller, launched the platform explicitly riding the coattails of Jordan Peterson, producing a series of documentaries on the lobster king. Along with other “sensemakers” of the Intellectual Dark Web, Peterson and the Weinsteins (Eric has a brother) are recurring guests. Furthermore, Rebel Wisdom co-founder Alex Beiner is also an Executive Director of the UK-based psychedelics conference Breaking Convention—when not acting as a retreat assistant at the elite psychedelic spa, Synthesis.

At minimum, the active promotion of extreme beliefs by those underwriting the psychedelic medicalization project affects the kinds of questions that researchers ask and the type of research that is deemed politically viable (see: veterans and PTSD). Such a realpolitik approach serves to further marginalize people whose lives and interests have historically been subjugated: those of the impoverished, women, POC, LGBTQ, disabled people, the criminalized, and the neurodivergent—a fact reflected in the paucity of psychedelic research dedicated to these demographics.

To probe further, the concern about psychedelics precipitating radical shifts in belief—political or religious—has its roots in psychedelics’ own peculiar history. And while psychedelics are currently putting on a proverbial suit and tie to make them both marketable and palatable to the mainstream, few care to discuss what happened the last time institutions had a free hand with these mind-bending chemicals. That era was defined by MK-Ultra, the CIA’s decades-long attempt to subvert people’s deepest convictions by any means possible. Though the majority of the evidence was deliberately destroyed, what we do know about MK-Ultra is extremely disturbing, and remains an unresolved, profound violation of human autonomy and public trust. Frankly, society hasn’t adequately addressed this institutional betrayal and there is no time like the present “psychedelic renaissance” to revisit these difficult topics. In other instances when human rights violations have become undeniable, a best practice for moving forward is truth and reconciliation. And if we are to avoid mistakes from the cannabis industry (which booms while many thousands remain incarcerated), this should precede entrepreneurs making their billions.

What we do know is that many of the educational institutions currently investing heavily in psychedelic research have dark histories of conducting research for the CIA (witting and unwitting) to weaponize the very drugs these same institutions seek to wield as the healer’s scalpel. Not all of this research was specifically using drugs. Documents obtained via Freedom of Information Act requests indicate that at least 80 institutions and 44 universities played some role in the effort to covertly and overtly bend people’s will to the aims of another. Notable mention goes to Johns Hopkins, Stanford, and Mount Sinai Hospital—each of which received funding from MK-Ultra and today are positioning themselves as potential leaders in the revivified psychedelic field. Even my present employer, The Ohio State University, was connected to two MK-Ultra subprojects.

While the CIA famously tried and failed to use psychedelics as mind control pills in MK-Ultra, one of its real “successes” grew from Canadian psychiatrist D. Ewen Cameron’s experiments with drugs, sleep, and sensory deprivation. Cameron’s work resulted in the KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation and Human Resource Exploitation Training Manual. As Naomi Klein points out in her hugely influential book, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, Cameron’s tests on human subjects were ultimately not used for mind control, but “to design a scientifically based system for extracting information from ‘resistant sources.’ In other words, torture.” Consequently, some of the techniques developed for KUBARK are being used in present-day US black sites and detention facilities such as Guantánamo Bay, which is now approaching its 20th anniversary.

In addition to information extraction, shock can soften a person to new information. According to social theorists, a crucial first step on the path to radicalization is something called a cognitive opening: an experience that jerks the person out of their routine, or causes them to question the foundation of their belief structures or worldview. This post-shock opening leaves the person vulnerable to, as Klein puts it: “Whatever ideas happen to be lying around.” Of course, Klein is discussing policy ideas post-crisis, but for the purposes of this discussion, her assertion appears relevant to understanding the psychology of radicalization.

In counterterrorism and radicalization literature, cognitive openings are usually characterized as resulting from an upsetting event—the disruption of a way of life or perhaps the loss of livelihood or a loved one—but strong psychedelic experiences can leave people feeling similarly shattered. In fact, a whole psychedelic integration industry has popped up to put Humpty-Dumpty back together again. But what if your integration therapist was also a fan of the Intellectual Dark Web? What if the person who introduced you to psychedelics also introduced you to Alex Jones, QAnon, or the Proud Boys? What if these dynamics are in play right now?

Conspirituality doesn’t require psychedelics. Alternative spirituality employs syncretism to create bespoke, transcendent liberations, while conspiracy theory complexifies into ever-more insidious cages. Synergies abound. But be it conspiracy theory or spiritual practice, toss psychedelics into the mix and watch the fireworks. Psychedelic conspirituality has already demonstrated itself as contiguous with COVID denialism and the far-right. As such, it is well past time to acknowledge that right-wing ideologues have already staked a claim in psychedelia from multiple angles—from straight-laced ex-Goldman Sachs bankers introducing their psychedelic start-ups on Fox News and demanding we “make psychedelics boring again” to unhinged acid heads preaching the gospel of Alex Jones at the Capitol.

To be clear, none of this should be taken as an argument that psychedelics themselves are shifting people’s ideologies in any particular way. Radicalization is too complicated to be attributable to a single cause, as outlined in Innuendo Studios’ excellent video, The Alt-Right Playbook: How to Radicalize a Normie. Rather, post-psychedelic neuroplasticity may leave some people vulnerable to the kind of stochastic terrorism that Trump, Fox News, and digital Nazis have employed for decades, culminating at the Capitol with a semiotic force that we forget at our own peril.

A core insight in antifascist organizing is that no one is going to protect your community for you. So how do we disrupt the infiltration of psychedelic spaces by the right? Talking about it is a good start. Apart from preventing far-right insurrection, the decriminalization of all drugs and increasing equitable access to care (healthcare, housing, and substance use treatment) is another solid goal. As of February 1st, 2021, this is the policy reality for the entire state of Oregon and there is no reason it cannot be achieved elsewhere.

Once people accept the reality that psychedelics won’t solve all the world’s problems, perhaps it will be harder for psychedelic community members to sell out marginalized people to outsider financial predators—collaborating with fascists to legalize psychedelics.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Brian Pace, PhD

Brian Pace, PhD is currently a lecturer who teaches Psychedelic Studies at The Ohio State University. He was trained as an evolutionary ecologist, specializing in phytochemistry, ethnobotany, and ecophysiology. His interest in life science was piqued as a teenager while experimenting with his own neurochemistry. Brian believes in the psychedelic society movement and other grassroots decriminalization efforts to find alternative policies to the imperial drug war. He did field work in Southern Mexico, the US midwestern prairie, and the Ecuadorian Amazon. For more than a decade, Brian has worked on agroecology and climate change. Along the way, he has taught several university courses on cannabis.