Does the First Amendment Protect Spiritual Cannabis Use? A D.C. Activist Plans to Argue For It

A group of cannabis activists held a demonstration outside the White House. They made a Jewish, Christian, Buddhist, non-sectarian, and Rasta prayer over the plant, seeking to highlight the spirituality of cannabis use.

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

Adam Eidinger, a founder of Washington, D.C.-based cannabis activist group DCMJ, will be in court on September 11, 2017 to face charges for public use of cannabis. The penalty is up to six months in jail. Eidinger plans to challenge the constitutionality of cannabis prohibition on First Amendment grounds.

“I have been offered a plea deal of three months in jail which I have refused and seems excessive,” Eidinger says, “especially because the crime is only a crime if its constitutional.”

On April 24th, 2017, Eidinger and a group of cannabis activists held a demonstration outside the White House. They made a Jewish, Christian, Buddhist, non-sectarian, and Rasta prayer over the plant, seeking to highlight the spirituality of cannabis use.

Eidinger and three other activists were arrested by Capitol Police after each lighting a cannabis joint. They were charged with public cannabis use in violation of D.C. law. “This peaceful direct action got under their skin and they are seeking real jail time for a working single dad,” Eidinger says.

Eidinger will represent himself at trial with the aid of an attorney, Mark Goldstone. Eidinger argues that cannabis prohibition denies the free exercise of religion guaranteed in the First Amendment. “[Mark and I] have worked on First Amendment cases I have been a defendant in in previous years. We have won most of the cases actually. Being my own lawyer or Pro-se allows me to make opening and closing arguments, as well as motions and objections. In any case, I plan to call many people who were at the interfaith service on April 24.”

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” It is this second clause—the free exercise clause—which Eidinger argues is undermined by cannabis prohibition. Can Congress make laws banning drugs if it violates one’s freedom of religious exercise? It’s an interesting question, but Eidinger is not the first to pose it. U.S. courts at the state and federal levels have grappled with this in similar cases for decades.

Cases From The Past

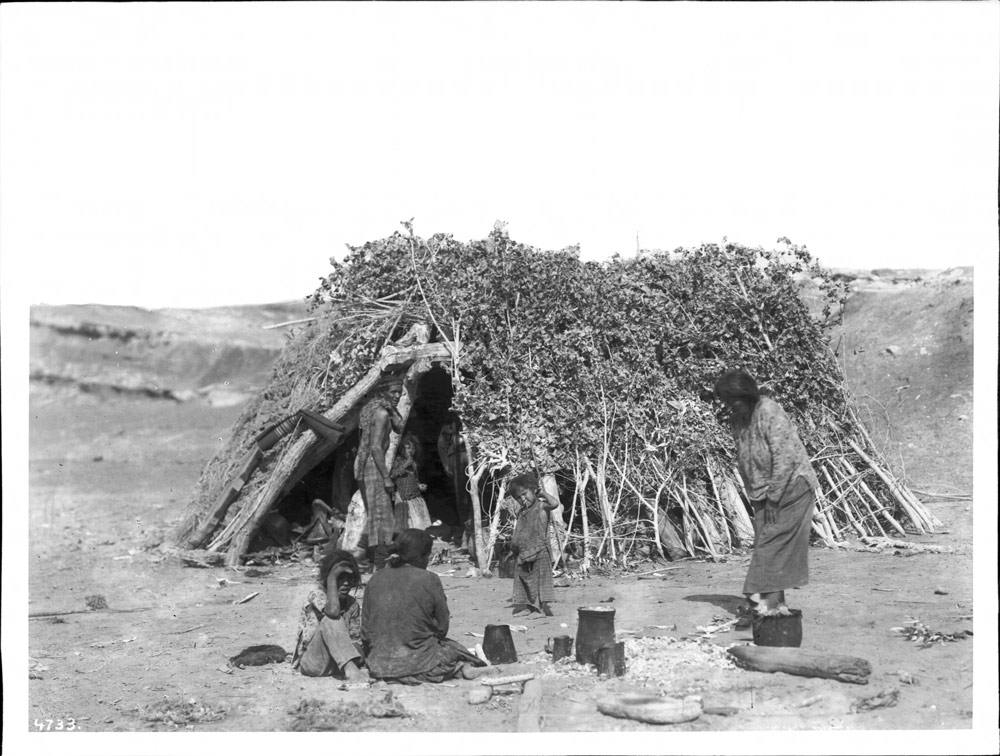

In 1964, the Supreme Court of California heard the case of People v. Woody (1964). This case involved a group of Navajos who were arrested in 1962 while using the peyote cactus, which contains the psychedelic mescaline. The trial court found them guilty of illegal possession of narcotics. This was affirmed by the Appellate Court, before the California Supreme Court reversed it.

They concluded the Navajos were protected by the First Amendment “since the defendants used the peyote in a bona fide pursuit of a religious faith, and since the practice does not frustrate a compelling interest of the state [emphasis added].” The court’s language was based on Sherbert v. Verner (1963), which established the “Sherbert test” to determine when a state has violated the free exercise clause.

The court conceded that although the right to free exercise is “absolute”, that doesn’t mean any practice is protected by the First Amendment. The state can regulate certain practices—but only if it can prove a “compelling interest” that outweighs the free exercise. An example is the case of Reynolds v. United States, where the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that polygamy in the Mormon church was not constitutionally protected, because of the dangers it posed to society.

People v. Woody touched on the question of what is a “bona fide” religious belief. We must distinguish, the court said, between those who practice their religion sincerely, and those who exploit the free exercise clause “merely as a cloak for illegal activities.” The court found that since the use of peyote was so central to the Navajo faith, it was a bona fide religious practice.

In weighing the individual’s free exercise against the state’s interests, the court found “the use of peyote presents only slight danger to the state…The scale tips in favor of the constitutional protection.” The court finishes their statement with a defense that makes one wonder if they themselves were using peyote: “In a mass society, which presses at every point toward conformity, the protection of a self-expression, however unique, of the individual and the group becomes ever more important. The varying currents of the subcultures that flow into the mainstream of our national life give it depth and beauty.”

The 1970 Controlled Substances Act established a system of controls and regulations on various drugs, including cannabis and other psychedelics. In practice and in writing, the U.S. government has recognized a special exemption for the “bona fide” use of peyote by members of the Native American Church. This understanding was based on existing legal precedent established by Woody and cases like it for over a decade.

But is this same protection afforded people who are not members of the Native American Church? This question came up in Native American Church of New York v. U.S. (1979). Here, a church in New York sued for their right to use psychedelics in a religious context. The Church, founded by Alan Birnbaum, was not affiliated with the Native American Church and few of its members were of Native American descent. However, they believed that all psychedelics—including peyote, cannabis, LSD, and more—were deities and wanted to use them freely in their practice.

The court concluded the law cannot restrict the peyote exemption to one particular church or group, and that any organization who used peyote sincerely in a religious context would be protected. However, the court would not let Birnbaum claim the exemption to use and distribute other psychedelics in his church besides peyote. The court noted the danger to society posed by psychedelics, and found that “[the plaintiff’s] interest still must be subordinated to the important purposes served by the Controlled Substances Act.”

The free exercise issue came up that same year with regards to cannabis in Jacquelyn R. Town v. State of Florida (1979). In this case, the Supreme Court of Florida affirmed a lower court’s ruling that the petitioner, Jacquelyn Town, may not use cannabis in her home for meetings of the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church. This faith is based in Jamaica and Miami, and draws influence from Marcus Garvey and Rastafari teachings. It considers cannabis use central to its faith. Again, the court found that “the state’s compelling interest outweighs the free exercise interests of the petitioner. To hold otherwise would, for all practical purposes, legalize the use of cannabis for anyone, member or nonmember of the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church, who came to [Town’s] residence to use the prohibited drug.”

In the early 1980’s, various members of this church were convicted in two separate trials in Florida and Maine of importation, distribution, and possession of cannabis. Law enforcement agents in both states collected a total of over 115 tons of cannabis. The church members’ free exercise defense was dismissed because the court found that the First Amendment did not protect smuggling cannabis into the country.

The free exercise question comes up in the famous case of Employment Division vs. Smith (1990). In this case, two members of the Native American Church in Oregon named Alfred Smith and Galen Black were fired from their jobs after testing positive for peyote. Their petition for state unemployment benefits was denied, because they were fired for work-related “misconduct”. They sued in response, and the appellate court found the state had violated their First Amendment rights. The state appealed, but the Oregon Supreme Court affirmed the decision.

The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled against Smith and Black. The Court reasoned that although the free exercise clause protects religious belief, it does not protect any religious activity from “neutral, generally applicable” laws of the state—meaning laws everyone must follow. Because the State of Oregon had a legitimate interest in banning peyote, one must not claim a religious exemption to the law. Justice Antonin Scalia recognized that this standard might disadvantage certain religious minorities but deemed “[this] must be preferred to a system in which each conscience is a law unto itself or in which judges weigh the social importance of … laws against … religious beliefs.” In this ruling, the court diminished the importance of the “Sherbert test” used for years and applied in the Woody case.

Public outcry from groups both liberal and conservative led to the passage in Congress—by near unanimous support—of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA). This reinstated the Sherbert test in federal and state law. The Act prohibited any government from “substantially burdening a person’s exercise of religion” even in generally applicable law. The only exception is if the burden “furthers a compelling governmental interest, and is the least restrictive means of furthering [that interest].” The Smith ruling had been thwarted.

But in 1997, the Supreme Court struck down the RFRA in City of Boerne v. Flores, ruling that it was unconstitutional as applied to the states and an improper exercise of Congress’s power. It remained in place as applied to the federal government.

This was confirmed in the case of Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficiente Uniao Do Vegetal (2006). This case concerns the Uniao do Vegetal (UDV) or Union of the Plants, a church based in New Mexico. This church made sacramental use of the psychedelic brew ‘hoasca’ (ayahuasca). In 1999, federal agents seized a shipment of the ayahuasca the church imported from Brazil. UDV sued the federal government and received a preliminary injunction against any further action towards the church. They cited the RFRA, stating that the state failed to show a “compelling interest” in its ban on their importation of the drug. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in their favor, concluding that their right to free exercise outweighed the state’s interest in regulating the drug. It compared their case to the religious exemption made for Native American use of peyote.

They remanded the case to lower courts for further proceedings. According to the American Law Division, “The Court’s decision does not establish a broad precedent for religious exemptions from criminal statutes….The Court made it clear that the government could not establish a compelling interest in simply enforcing an existing statute; there must be some other justification for the burden on religious expression.”

A smaller case dealt with a very similar issue. In Guam v. Guerrero (2002), the U.S. Court of Appeals found that the RFRA protected individual possession of a drug—but not its importation. Here, a Rastafari man named Iyah Ben Makhana (b. Guerrero) was arrested at the Guam international airport with several ounces of cannabis, and charged with drug importation.

His religious defense was partially dismissed. The court concluded Ben Makhana’s possession of cannabis was justifiable, but not his importation of it. “Rastafarianism,” the court reasoned, “does not require importation of a controlled substance, which increases the availability of controlled substances and makes it harder for Guam to control.” This odd ruling was summarized by Ben Makhana’s lawyer: “[This is] equivalent to saying wine is a necessary sacrament for some Christians but you have to grow your own grapes.”

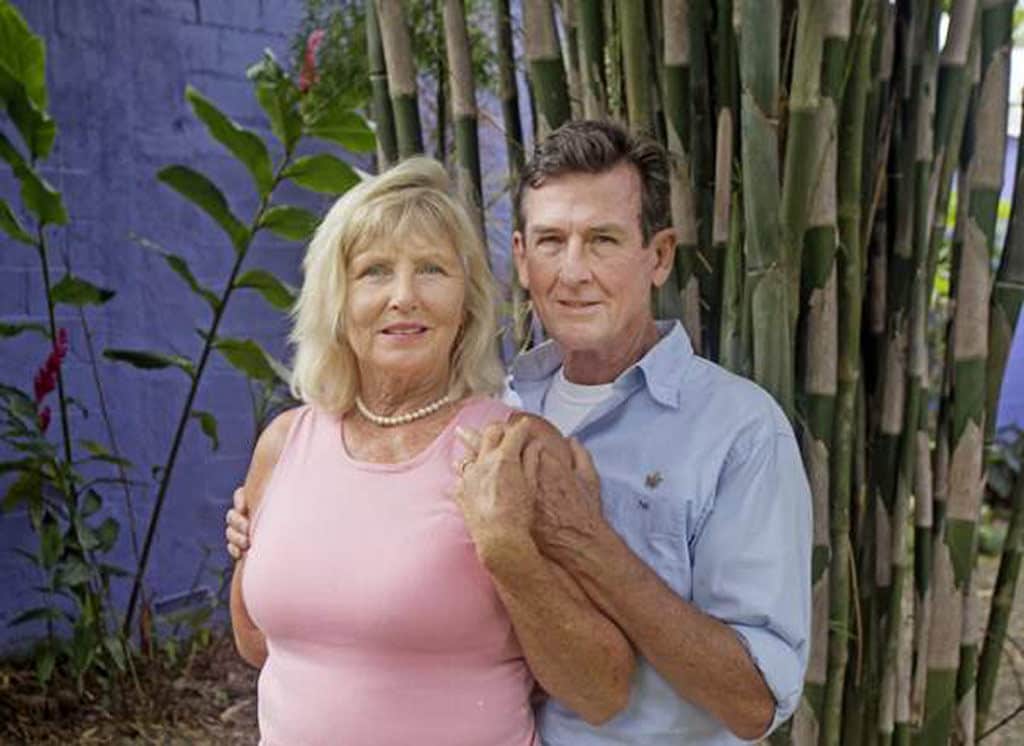

Ben Makhana had limited success. But we turn now to the most disappointing story concerning this question—that of Reverend Roger Christie. Christie founded The Hawai’i Cannabis (THC) Ministry in 2000, after being ordained as a minister to perform marriages with “cannabis sacrament”. In 10 years, his church’s membership grew to 50,000 and he performed weed marriages, weed funerals, and weed baptisms. VICE News writes, “Miraculously, [Hawaii] pretty much agreed with his interpretation, allowing him to form a church around the drug and practice uninterrupted for nearly ten years.”

But in 2010, Christie’s ministry was raided after a two-year long DEA investigation. He and 12 others were arrested, including his wife, and indicted by a grand jury for counts of marijuana trafficking.

Christie’s defense citing the RFRA was first upheld by U.S. District Court Judge Leslie Kobayashi, who found Christie’s practices sincere and legitimate according to the law. But the same judge reversed course one week later and rejected his defense. She refused to make a religious exemption for a Schedule I drug, citing its danger. In a move that echoes the Town case, the court also claimed Christie’s ministry might allow people with a fake ID to access the church and its cannabis and use it for a non-religious purpose (Christie denies this ever happened). However, Christie did defeat the charge that his ministry was a front for a drug-trafficking ring.

It is difficult to know which lessons to take away from this peculiar case, but if nothing else it reveals that strictly legal concerns are often subservient to mere political concerns. Reverend Christie tells us that he and his wife are fighting to overturn their convictions, and are awaiting a final ruling as of the writing of this article.

Back to the Present—How Will the Court Rule?

Looking at the legal history of this issue, one cannot clearly predict the outcome of Eidenger’s case in Washington, D.C. Clearly, the U.S. government at both the federal and state level—and courts at every level—have for decades recognized that some forms of illegal drug use are protected by the free exercise clause of the First Amendment. But context is of utmost importance.

What is the state’s compelling interest, if any, for restricting Eidinger’s ability to smoke? Is Eidinger’s cannabis use a bona fide religious expression, and if so, how could he prove it? Is this expression central to his religious practice, or is it secondary to other, more important aspects of his faith? And if it is a true religious expression, is a federal property in Washington, D.C. an appropriate venue for him to make it? These are all important questions that must be tackled in his trial. There is no sure road here to success–—nor an inevitable path to failure.

If you want to assist Eidinger and DCMJ in this legal effort — or just offer your support — you can contact them here.

Correction: September 28, 2017: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Roger Christie was convicted of drug trafficking. He was charged but not convicted.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.