Aldous Huxley on the decline of mental health following “progress” in capitalist democracies

“In this field prevention is incomparably more important than cure; for cure merely returns the patient to an environment which begets mental illness. But how is prevention to be achieved? That is the sixty-four-billion-dollar question.”

Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We rely on contributions from our readers and listeners. Your support is vital to sustaining Psymposia.

Support Psymposia’s independent journalism on Patreon and help us drive the Mystery Machine! We’re a bunch of meddling kids who are unmasking the latest shenanigans on the psychedelics beat.

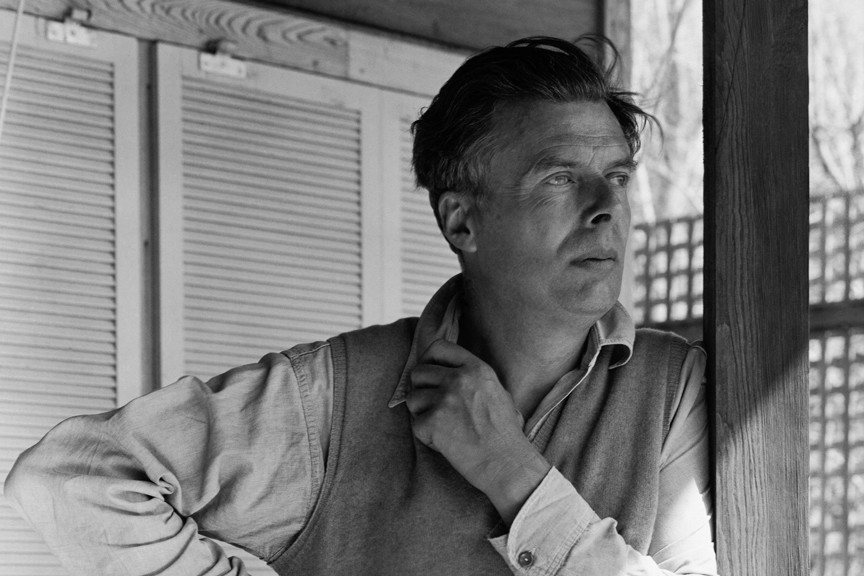

English author Aldous Huxley is known for being an early proponent of synthetic psychedelics and for his prophetic warnings about the results of progress. He wrote in his best known novel, Brave New World, that “one can’t have something for nothing.” There is always a price for “progress”; sometimes, perhaps often, it outweighs the benefits. Brave New World describes a future where independence is forbidden, where humans are drugged with the “perfect tranquilizer” and brainwashed to accept their place in society. Government authority, happiness, and consumerism are valued above all else. Huxley produced a large catalogue of essays, books, and interviews warning of the potential negative effects he believed would accompany new developments in science and technology—effects which we have had the honor of watching play out first hand.

Huxley (1894-1963) was born into an age of scientific optimism. Authors like H. G. Wells and Jules Verne painted fabulous pictures of an imagined scientific future to come. The reality of the world Huxley grew up in painted a different one. Europeans who lived through the early 20th century had seen the “first modern war” (which decimated their male population by 6 percent in the UK, 12 percent in France and Germany, and 20 percent in Serbia), the Great Depression, the break up of traditional communities, and the rise of totalitarian communism and fascism.

Huxley felt reality departed so far from the scientific progress promised that he wrote his dystopian novel as a satire of the out-of-date H. G. Wells. Huxley was far from alone, these events left deep scars on the European psyche. In 1940 German philosopher Walter Benjamin wrote during his exile in Paris:

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

As a Jewish Marxist, Benjamin saw the writing on the wall when France fell to the Nazis. Soon after, he killed himself in the Pyrenees, having failed to secure passage to the US.

Huxley was not strictly against scientific progress, “All technology is in itself moral and neutral. These are just powers which can either be used well or ill.” He would frequently call on scientists to solve pressing issues. For example, alleviating the Great Powers’ temptations to declare war in the Middle East by investing in alternatives to petroleum, such as wind and solar energy. Nor did he obtusely turn a blind eye to the century’s social progress. Huxley simply felt that if “progress” was not in service to humanity, one could not say it made the world a better place, in many cases quite the opposite.

In illuminating the shadows of the “progress” of his time, Huxley found many troubling developments. He concerned himself greatly with the erosion of personal rights. In capitalist democracies he saw the main danger as increased centralization. In 1958 he wrote:

But the progress of technology has led and is still leading to…a concentration and centralization of power…In a world of mass production and mass distribution the Little Man, with his inadequate stock of working capital, is at a grave disadvantage. In competition with the Big Man, he loses his money and finally his very existence as an independent producer; the Big Man has gobbled him up. As the Little Men disappear, more and more economic power comes to be wielded by fewer and fewer people… This Power Elite directly employs several millions of the country’s working force in its factories, offices and stores, controls many millions more by lending them the money to buy its products, and, through its ownership of the media of mass communication, influences the thoughts, the feelings and the actions of virtually everybody.

Unlike his contemporary Orwell, Huxley did not see future despotism as something sustained by terror or physical violence, stating, “You can do everything with bayonets except sit on them.” For Huxley, long-term tyranny required the consent of the people. As in Brave New World, he believed people would come to love their slavery, and advances in propaganda and mass media could allow this. In America, he saw great danger in the sophistication of advertising. In children singing commercial slogans, he saw firms conditioning them for future consumerism. And the political implications of this sophistication were more worrying. The 1956 presidential election made great use of marketing theories and merchandising candidates, which Huxley saw as undermining the democratic process:

Democracy depends on the individual voter making an intelligent and rational choice for what he regards as his enlightened self-interest, in any given circumstance. But what [marketers] are doing, I mean what both, for their particular purposes for selling goods and the dictatorial propagandists are doing, is to try to bypass the rational side of man and to appeal directly to these unconscious forces below the surface. So that you are, in a way, making nonsense of the whole democratic procedure, which is based on conscious choice on rational ground.

While it may sound like Huxley was an eternal pessimist, this was not the case. Huxley’s calls for people to step back and examine whether scientific innovations had humane values, at their heart, stemmed from a sense of optimism; it is never too late for us to change our ways. The serious approach Huxley wished to take toward new advancements can be seen in his reaction to the Psychopharmacological Revolution, which he described in a 1958 issue of the Saturday Evening Post:

We ought to start immediately to give some serious thought to the problem of the new mind changers. How ought they to be used? How can they be abused? Will human beings be better and happier for their discovery? Or worse and more miserable?

The matter requires to be examined from many points of view. It is simultaneously a question for biochemists and physicians, for psychologists and social anthropologists, for legislators and law-enforcement officers. And finally it is an ethical question and a religious question. Sooner or later-and the sooner, the better-the various specialists concerned will have to meet, discuss and then decide, in the light of the best available evidence and the most imaginative kind of foresight, what should be done.

Huxley dedicated a lot of thought to the subject of drugs and drug use. He frequently worried about their potential as agents of control, but also saw in them the potential for spiritual and psychological release. At the age of 59 he took mescaline and wrote about his experiences and philosophies in Doors of Perception (1954). He expanded on these ideas in Heaven and Hell (1956) after taking LSD. For Huxley, drug use would always exist, as:

Most men and women lead lives at worst so painful, at best so monotonous, poor, and limited that the urge to escape, the longing to transcend themselves if only for a few moments, is and has always been one of the principal appetites of the soul. Art and religion, [etc.]… all these have served, in H.G. Wells’s phrase, as Doors in the Wall. And for private, for everyday use there have always been chemical intoxicants.

However, Huxley was unimpressed with the chemical “Doors in the Wall” available. Alcohol, tobacco, opium and cocaine all carried heavy side effects. There were of course the new tranquilizers, which had medical uses, but he thought they acted as uninspiring agents for self-transcendence. Yet, prohibition was not the answer to these unhealthy habits:

The universal and ever-present urge to self-transcendence is not to be abolished by slamming the currently popular Doors in the Wall. The only reasonable policy is to open other, better doors in the hope of inducing men and women to exchange their old bad habits for new and less harmful ones. Some of these other, better doors will be social and technological in nature, others religious or psychological, others dietic, educational, athletic. But the need for frequent chemical vacations from intolerable selfhood and repulsive surroundings will undoubtedly remain. What is needed is a new drug which will relieve and console our suffering species without doing more harm in the long run than it does good in the short… it should produce changes in consciousness more interesting, more intrinsically valuable than mere sedation or dreaminess, delusions of omnipotence, or release from inhibition.

Huxley saw mescaline and LSD as a giant step in this direction and wrote with great enthusiasm about the effect they would have on society. He saw it as an opportunity for men and women to achieve genuine religious experiences and temporary self-transcendence. He felt this would make traditional religion redundant:

To men and women who have had direct experience of self-transcendence into the mind’s Other World of vision and union with the nature of things, a religion of mere symbols is not likely to be very satisfying. The perusal of a page from even the most beautifully written cookbook is no substitute for the eating of dinner. We are exhorted to “taste and see that the Lord is good.”

In one of his predictions he wrote the “revival of religion…will not come about as the result of evangelistic mass meetings or the television appearances of photogenic clergymen,” but as a result of self-transcending biochemical discoveries.

These theories on drugs were influential on a medical profession attempting to make sense of an explosive demand for mood-altering drugs. The Doors of Perception was well received by the British medical profession. In the British Medical Journal, the Head Psychologist at St Thomas’ Hospital London, William Sargent, reviewed it very positively:

This book should be very interesting reading to doctors and especially to psychiatrists. It will make us even more uneasy at our present failure to relieve so much of the mental suffering of our patients, so vividly brought to life by this book. It may put in better perspective our some times too detached philosophic viewpoints on such problems.

However, this influence would wane after his death in 1963. The drug scares and anti-psychedelic wave of the 1960s had a large effect on the medical profession. Czech Psychiatrist Stanislov Grof complained that, “although the reports of two decades of scientific experimentation with LSD were available in psychiatric and psychological literature, [mental health professionals] allowed their image of this drug to be formed by newspaper headlines.”

In this environment, Huxley’s self experimentation was no longer acceptable. Its popularity in the “hippie” scene did not help matters (Jim Morrison would name his band The Doors as a tribute to the book). While Huxley was perhaps too prestigious and his writings too notable to be attacked directly, Doors of Perception was written off as a bad influence in medical journals. Celebrations of Huxley in literary journals and the general media would often barely mention it; if they did, any complimentary descriptions were heavily caveated so as to not promote drug use.

In 1971, Britain formalized its anti-drug stance with the Misuse of Drugs Act and Nixon would initiate the War on Drugs. Popular philosophical investigations into drugs and drug use diminished. The tone shifted and became more combative, with the “War on Drugs” dominating the discourse. It is hard to imagine a book like Doors of Perception being published in the proceeding decades, let alone a shameless, philosophical discussion of drug use in a popular magazine like the one Huxley wrote for The Saturday Evening Post. There are many well-reported negative side effects of the War on Drugs, less explored is its silencing of such discussions in popular discourse. Yet, the continued rise of drug use and addiction demonstrates that greater need.

Of course, psychedelics are currently making a comeback. It is hard to imagine Huxley would not cast a worried thought (or more likely essay) toward its capitalistic resurgence. Plus Three’s “Dear Psychedelic Researchers” offers a Huxleyan plea to take a step back and remember the point of all this: working towards greater mental health and better lives. The solution to which ultimately lies beyond the products of pharmaceutical companies, but instead, in the nature of the societies in which we participate. It is a subject Huxley wrote about 64 years in the past and the need to point it out will probably still be with us 64 years in the future:

Technological and economic progress seems to have been accompanied by psychological regress. The incidence of neuroses and psychoses is apparently on the increase. Still larger hospitals, yet kinder treatment of patients, more psychiatrists and better pills – we need them all and need them urgently. But they will not solve our problem. In this field prevention is incomparably more important than cure; for cure merely returns the patient to an environment which begets mental illness. But how is prevention to be achieved? That is the sixty-four-billion-dollar question.

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Alex Brown

Alex Brown is the researcher, writer and producer of drug history podcast Hooked on History. He has a Master's in Contemporary History from the University of Edinburgh.