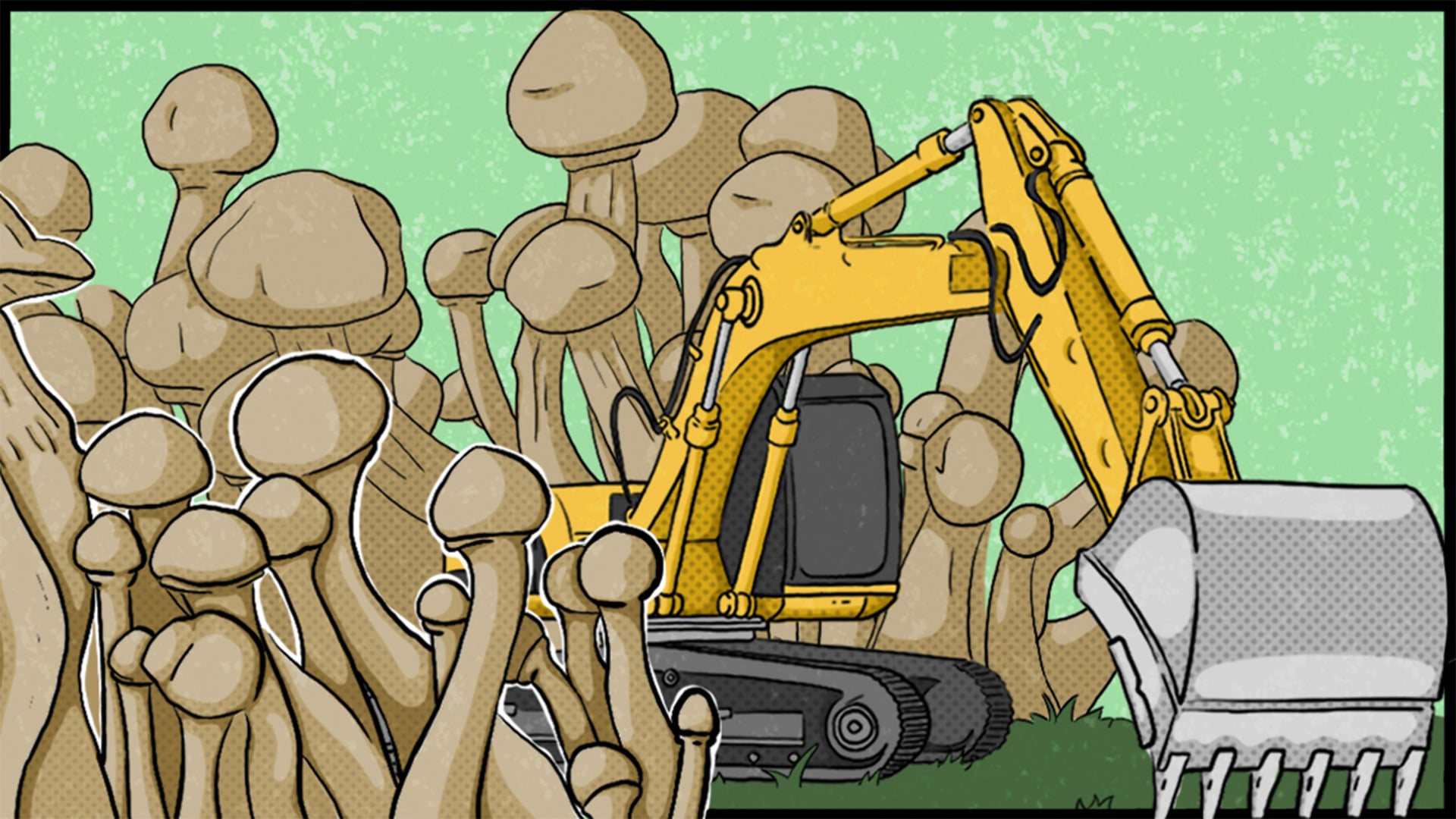

This is Part One of “From Mining to Mushrooms,” a series exploring the infiltration of the psychedelic pharmaceutical industry by companies, investors, and executives from extractive industry. Read Part Two and Three.

To read Psymposia’s interview with Thea Riofrancos, an expert on Latin American resource conflict, click here. For a long list of psychedelic-mining industry ties, click here.

At the 2020 Psychedelic Liberty Summit, longtime cannabis activist Steven DeAngelo addressed one of the elephants in the room concerning the blossoming psychedelic industry: the wresting of agency from those connected culturally, spiritually, and idealistically to psychedelics, by those who see psychedelics as the next exploitable resource to sell to the masses.

DeAngelo founded one of the first cannabis dispensaries in the United States—Harborside in Oakland, California—and helped create the ArcView Group in 2010, with the mission to develop the first cannabis-focused investment group. He knows firsthand how the corrosive effects of capitalism can eat away at the cultural values of once-subversive cultures.

“With Arcview, we hit on the energy of free enterprise to power the social change we wanted, and a lot of the progress we made is because we did invite the investor class in, but it came at a cost, a significant cost,” DeAngelo said. “Prior to Arcview inviting the investor class in, the movement was driven by people who loved cannabis, but we attracted a lot of people whose motivation was not love of cannabis but love of making money.”

ArcView’s investor network now includes over 600 accredited investors who have reportedly injected more than $260M into hundreds of cannabis-focused companies. And, while this is undeniably a great achievement for some and has served to normalize the drug to an extent, DeAngelo was surprised by the speed at which the cannabis industry was devoured by big business.

He worries that the same thing could happen to psychedelics. (See “Suddenly, Psychedelics Are Big Business.”)

“Cannabis lovers took investment money and then ceded control to investors,” he said. “I saw a lot of people who had spent their lives representing the plant start to lose power, their livelihoods, and their influence over how to explain cannabis to the rest of the world. I fear we could see a lot of the same thing with psychedelics. If that happens, the way these substances are taught to the world is going to change. We could see a model for psychedelics more geared to return for investors than toward a meaningful experience for an individual or for positive social change.”

Many of those who endorse the incorporation of the free market as the best way to introduce psychedelics to the “mainstream” world point to the drugs’ potential to alleviate the mental suffering of millions, increase environmental awareness, and help usher in a new wave of so-called “conscious capitalism.”

But, what if many of the same people who have been profiting at the expense of others’ health and the health of the environment are stepping into the ranks of those responsible for bringing psychedelics to market?

As it turns out, this is not such a hypothetical question. Individuals with extensive histories in the mining industry are entering the psychedelic pharmaceutical industry as speculative investors and executives.

Manganese, Lithium, and Psychedelics: The Next Big Wave…For Speculative Investors

In October of 2019, a group of surveyors affiliated with AIS Resources (AIS)—a Vancouver-based investment corporation with a history of lithium and manganese extraction in South America—visited a manganese mine near Palenque, Panama. (No, not the Palenque in Mexico where the esteemed ethnobotany conferences were held—about 1,500 miles southeast of that). The 60-meter-deep mine shaft they had come to explore was last used to extract manganese in the 1990s, but has remained inactive since then. AIS, intent on finding new sites to tap for manganese, took geological samples from near the dormant mine shaft which, when assessed, showed high levels of manganese.

The company announced these results in a press release titled, “AIS Signs LOI [letter of intent] to Exploit Manganese Deposit in Panama,” in which it explained that it had entered into an agreement with the landowner of the mine and surrounding area, granting AIS exclusive exploration rights to the area while they determined the feasibility of recommencing mining operations in the area. Assuming manganese mining is brought back to this land, AIS estimates that it will extract up to 350 tonnes from the land per day, and up to 10,000 tonnes per month.

For the investors over 5,000 miles away in Vancouver, Canada, this looks to be a huge win. It’s another entry to add to the company’s expanding portfolio of global resource extraction endeavors—up to this point mostly centered around manganese trading through partners in northern Peru and gold mining projects in Australia.

Extractive practices and operations are hardly a win for local populations who have experienced water pollution, environmental destruction, and health issues such as higher rates of “rickets-like skeletal deformations,” as described in a 2011 study on children living near open manganese mines in Ukraine.

AIS’ chairman Martyn Element talks about the potential for manganese and lithium in a similar way to how investors have begun talking about psychedelics: as the next big money-making wave on the horizon. Companies like Tesla and Mercedes Benz, which are looking to increase their production of electric vehicles, are forward-buying manganese and lithium—two essential materials in the batteries of electric vehicles—because, “when the wave comes, it’s going to be bigger than anybody would ever estimate,” Element said. AIS is banking on this wave, and setting up partnerships with mining projects throughout South America and Africa, speculating on the increase in demand.

While it is of paramount importance to decarbonize and shift our energy consumption toward more renewable models, there is a reality in which this shift could still be quite environmentally destructive.

Psymposia reached out to Dr. Thea Riofrancos—an assistant professor of political science at Providence College, who researches Latin American conflicts over resources and the implications of a global energy transition—about this potential destruction. Riofrancos said that a shift to renewable energy could still be taxing on the environment if production is tailored to the idea that everyone should still individually own an electric vehicle. This is the world that automobile manufacturers and their suppliers are hoping to capitalize on. But, compared to typical internal combustion vehicles, individual electric vehicles actually require more mined resources to produce.

Addressing issues of environmental destruction in the context of a global energy transition away from fossil fuels and from current levels of extractive industry requires re-assessing our systems of transportation, in general, according to Dr. Riofrancos.

“I would prefer a different model of transit for many reasons, including that it’s less resource-intensive,” Riofrancos said, promoting more public transit, mass transit, and biking as ways to reduce our reliance on cars. “Anyone reading a lot of this stuff [about transitioning to electric power] could be left thinking there is no way to electrify transit without just extracting an enormous amount of stuff. But, again, that presumes a certain outcome [of individual car dominance] and we should question that in general.”

Mining firms like AIS and the industries they support justify their practices with claims that electric vehicles will cure the world’s environmental issues, while ignoring the intense resource extraction, pollution, and political destabilization required to sustain the present car-centric paradigm of transportation.

In a similar way, psychedelic pharmaceutical companies like ATAI Life Sciences claim that they will “ultimately cure mental health disorders,” like depression, anxiety, and addiction—mental health issues perpetuated by the same economic realities that underpin biotech and big pharma. ATAI founder, Christian Angermayer, has repeatedly championed capitalism as the solution to the world’s problems—a framing which masks its role in these crises—even as he and his colleagues perpetuate the problems they “ultimately” want to solve.

Plutocrats who pursue “altruistic profits”—through mining and pharmaceuticals—while failing to actually address systemic issues are not mutually exclusive. It appears that philosophies and executives from extractive firms like AIS are bleeding over directly into the psychedelic pharma industry.

Extractive Alumni

When digging into the ties between extractive firms, like AIS, and the emerging psychedelic pharmaceutical industry, the web of connections becomes increasingly complex.

AIS has graduated at least two alumni from its ranks into the for-profit psychedelic pharmaceutical industry: Marc Enright-Morin and Luke Montaine. Each of them have long histories in extractive industries and made quick pivots into psychedelic pharma when it became clear that there was money to be made.

ThinkMyco

Marc Enright-Morin served as AIS CEO from 2016 to 2018, and held the position of CEO at the lithium mining and exploration company Ultra Lithium for nearly seven years before that.

After leaving AIS, Enright-Morin co-founded ThinkMyco: a self-described “vertically integrated mycology technology company.”

According to ThinkMyco’s investor pitch deck, the company intended to develop ways to produce mushrooms at large scales through “automation and disruptive mushroom growing technology;” sell functional foods and nutraceuticals, such as mushroom jerkies and reishi mushroom supplements, and; conduct research into neurogenic pharmaceutical drugs in hopes of “commercializing new fungi bio-technology.”

ThinkMyco’s other co-founders also have ties to mining. Co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer Brian Bapty was President and Director of Confederation Minerals—a company focused on acquisitions and development of mineral deposits in North America. And, Co-Founder and Chairman Bradley Birarda previously founded gold and mineral extraction companies Canaco Resources and Continental Gold.

During the course of reporting this story—and after ThinkMyco’s Chief Technology Officer, Nikita Alexandrov, authored a widely-shared “2020 Psychedelic Industry Insights Report”—the company virtually disappeared. ThinkMyco appears to have fallen into chaos after disagreements over Bapty’s and Birarda’s leadership decisions regarding COVID-19.

When reached for comment, Alexandrov told Psymposia that “ThinkMyco went underwater during the pandemic, we had some internal disagreements.” According to Alexandrov, Birarda and Bapty did not follow Covid-19 workplace safety measures, resulting in many staff members getting sick. When Alexandrov got sick, quarantined, and eventually went to be with family, he was ignored by management and eventually stopped getting paid.

In response to Psymposia’s inquiry about what happened to ThinkMyco, Enright-Morin responded, “Founders did not get along.”

Psymposia has reached out to Bapty and Birarda for comment on the status of ThinkMyco, but has not received any response as of publishing.

Roadman Investments Corp.

Another executive hailing from AIS is Luke Montaine, who currently serves as the CEO of Roadman Investments Corp., which recently began investing in the psychedelic pharmaceutical industry.

Roadman announced the investor-focused Denver Psychedelic Summit (which does not seem to have ever taken place), and has invested in Champignon Brands, a company “capitalizing on the emergence of psychedelic medicines for mental health conditions,” according to its website. Roadman has a controlling stake in psychedelic retreat center, Psychedelic Insights, as well. And, the company also recruited Kevin Matthews—the Founder and Executive Director of non-profit SPORE and former campaign director of the Denver Psilocybin Initiative—onto its advisory board. When reached for comment, Matthews said that he stopped advising Roadman in November of 2019.

Montaine was previously the Vice President of corporate finance for AIS, worked on corporate development for the gold and silver mining company the iMining Group, and served as Vice President of corporate finance for Element & Associates—AIS’ Chairman, Martyn Element’s, platform for pursuing global business ventures.

Montaine previously served on the board of Urban Select Capital Corp., which—among other things—invested in multiple mining and resource extraction operations throughout Canada and Asia. The company acquired numerous mining companies, including Granja Gold and Hard Rock Lithium Corp.

Here’s the interesting part, though—Urban Select Capital Corp. and Roadman Investments Corp. are actually the same company.

In April of 2019, Urban Select changed its name to Roadman Investments Corp. and undertook “comprehensive corporate rebranding initiatives to coincide with the planned name [change.]”

Since then, Roadman has been focused on psychedelic pharmaceuticals and plant-based nutraceuticals, with Montaine at the helm. According to Montaine, Roadman still owns 100 percent of Urban Select’s prior investment, Hard Rock Lithium, but you won’t find any reference to mining in its new investor presentation or on its website. And, Roadman brought over staff from Urban Select, too.

Min Kuang, a director at Roadman, previously served as CEO of Urban Select Exploration Inc.—a resource and mineral exploration arm of Urban Select. Kuang was also an advisor for Granja Gold and the founder of Orient Ventures Inc., which had partnerships with Nickel North Exploration Corp.—an exploration outfit focused on searching for nickel, copper, and platinum in Canada.

Urban Select’s Chief Financial Officer (CFO) David Yoo also retained his position as CFO at Roadman. However, Montaine took over as interim CFO in March, 2020, after Yoo resigned.

So, why would Roadman—a firm whose investments prior to 2019 largely consisted of mining operations—ultimately change its name and enter the rapidly growing psychedelics industry? Well, speculation and profits, of course.

“I didn’t like the name Urban Select,” Montaine told Psymposia over email. “Psychedelics I believe is going to be the next wave of excitement and development. Cannabis had it’s [sic] fun for a few years and is overvalued and quiet now. Currently the $ is in psychedelics we believe.”

Hey! Before you go… Psymposia is a 501(c)(3) non-profit media organization that offers critical perspectives on drugs, politics, and culture. We strive to ask challenging questions, and we’re committed to independent reporting, critical analysis, and holding those who wield power accountable.

Our perspectives are informed by critical analysis of the systemic crises of capitalism that have directly contributed to the unmitigated growth of addiction, depression, suicide, and the unraveling of our social relations. The same economic elite and powerful corporate interests who have profited from causing these problems are now proposing “solutions”—solutions which both line their pockets and mask the necessity of structural change.

In order for us to keep unpacking these issues and informing our audience, we need your continuing support. You can sustain Psymposia by becoming a supporter for as little as $2 a month.

Russell Hausfeld

Russell Hausfeld is an investigative journalist and illustrator living in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism and Religious Studies from the University of Cincinnati. His work with Psymposia has been cited in Vice, The Nation, Frontiers in Psychology, New York Magazine’s “Cover Story: Power Trip” podcast, the Daily Beast, the Outlaw Report, Harm Reduction Journal, and more.